I often think painfully of godly students or friends who died quite young—for example, Caritha Clarke, Nabeel Qureshi, Aaron Nickerson, and most recently Brittany Buchanan Douglas. The news of these events made little sense to me emotionally, though I have confidence in each case that they are celebrating now; they made it to God’s throne ahead of me. With less sorrow, I think of godly friends (or my wife or myself) who suffered but experienced healing and restoration in this life.

You won’t have to read many of my blog posts to figure out that I believe God does miracles. But if you’ve been around very long, you probably also know some people who haven’t experienced healing, despite much prayer. You undoubtedly know godly people who have experienced tragedies. Some of us live through our tragedies and find happiness on the other side, but that not everyone does is itself often part of our experience of tragedy.

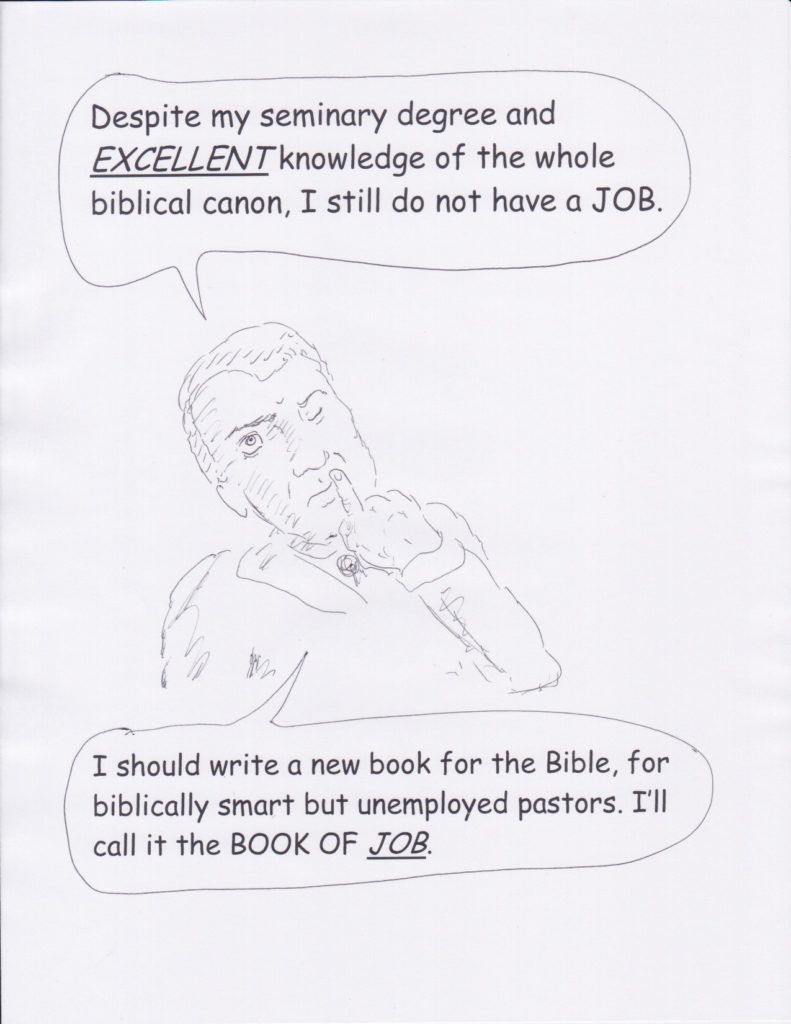

How do we make sense of these things? Sometimes those of us who are theologically inclined bristle at leaving some things a mystery, such as why one person is healed (sometimes even in inexplicably dramatic ways) and another person isn’t. Although there are definitely principles that change outcomes in many cases, there are some exceptions to all our humanly devised theological rules.

The Book of Job addressed God’s people facing tragedy and not understanding why. For those who persevere it offers hope (James 5:11), whether in the short run or the long run. Sandwiched between its narrative introduction and its narrative conclusion, most of the book consists of Job’s poetic dialogues with his “comforters,” who actually prove to be rather “sorry” (NASB) or “miserable” (ESV, KJV, NET, NIV, NRSV, WEB) comforters (Job 16:2). They withhold kindness and prove to be fair-weather friends (6:14-17, 21a).

Job’s comforters start out helpfully, lamenting with Job and staying silent for seven days (Job 2:12-13). They mourn with those who mourn, sharing Job’s pain. If they would have just kept their mouths shut the story would have taken a different turn. Instead, they soon begin spouting conventional wisdom, providing many wise sayings but misapplying them to Job’s case. Knowledge can be applied in foolish ways: “The legs of a disabled person hang limp; so does a proverb in the mouth of a fool” (Prov 26:7 NRSV); “Like a thorn that falls into the hand of a drunkard, so is a proverb in the mouth of fools” (26:9 NASB).

Job didn’t need their theology lesson about why he was suffering. Job already knew the sorts of “wisdom” they were unloading on him: “What you know, I also know; I am not inferior to you” (Job 13:2, NRSV). He really didn’t need them to justify God by condemning him: “If you would only keep silent, that would be your wisdom!” (13:5).

Job’s friends kept insisting—and more so as the conversation progressed—that God is righteous and punishes the wicked. That, of course, is true. But they also kept insisting—and again more so as the conversation progressed—that this meant that Job must have sinned. Job didn’t understand his situation, but he knew that he wasn’t being punished for impiety. Certainly he at least was no worse than his accusers. So he pushed back—and himself the more so as the conversation progressed—insisting that he was innocent and that God would not justly find fault with him. God’s power is unlimited, but if God heard Job’s plea he would vindicate him.

In the book’s closing chapters, God calls to account both Job and his friends. God first answers Job at length (Job 38—41). Does Job understand all the secrets of creation, all the interests that God must wisely balance in bringing to pass his purposes? Before God’s infinite majesty, Job confesses his own inadequate understanding of the divine purpose (42:2-6; esp. 42:3 with 38:2). But God also speaks, far more concisely, to the leading voice among Job’s friends. (God sidesteps directly answering the speech of Elihu in Job 32—37; scholars differ as to whether this is because Elihu voices God’s perspective or does not even merit an answer!)

To Job’s chief comforter, God replies: “I am angry with you and your two friends, because you have not spoken the truth about me, as my servant Job has.So now take seven bulls and seven rams and go to my servant Job and sacrifice a burnt offering for yourselves. My servant Job will pray for you, and I will accept his prayer and not deal with you according to your folly. You have not spoken the truth about me, as my servant Job has” (Job 42:7-8, NIV).

Indeed, Job was more righteous than they, and while God would reprove Job’s pretense of understanding, he would defend Job before his friends. They submitted to God immediately, and God answered Job’s prayer to forgive them.

In one way, God reproved both Job and his friends, because in a sense they both misunderstood God’s ways. Job’s friends believed that bad things should happen only to bad people, and therefore Job was bad. They were theologically wrong, and their assumption that Job had merited his suffering was morally wrong, misjudging Job and contributing further to his suffering.

Job misunderstood God’s ways in a slightly different sense. Backed into a rhetorical corner by his accusers, he kept insisting that he was not a bad person, and that God should vindicate him. Yet Job was still partly working from the wrong assumption that his friends shared: that bad things should happen only to bad people. God’s answer to Job was to show his glorious design in nature, that his wisdom is beyond our wisdom, and therefore to leave us back at the bothersome answer we often want to dismiss at the beginning as simplistic.

We may be welcome to explore and seek for greater knowledge, but we are finite and some things will always be a mystery to our limited intellects (cf. Deut 29:29; Prov 25:2). We know enough that we should trust the Lord who is smarter than we are when there are some things we don’t know. If we think we can explain adequately all the Lord’s ways, we, like Job, may learn otherwise when we stand before him (Job 42:5-6).

God never explains to Job the backroom discussion with the superhuman accuser (Job 1—2) who is far more powerful than Job’s earthly accusers. He never explains the sorts of celestial negotiations that may go on behind the scenes, to which we are normally not privy except when he grants special revelation. Job doesn’t need to know those things, and wouldn’t have been prepared to understand them in his era if he had. He does need to remember that God is trustworthy no matter what. Further, Job may be innocent with regard to the suffering, but that is beside the point. His own right hand cannot deliver him (Job 40:14). In NT language, God’s blessing comes by grace.

In any case, Job was right that he had not merited his suffering, and his friends acted sinfully when they judged him. Unless God provides insight into a given case, we don’t know why a given person is suffering. Looking down on them is sometimes a way of distancing ourselves from having to consider that we could experience suffering ourselves. “You see my suffering and are afraid” (Job 6:21b).

Others do not assume that the suffering have sinned, but they assume that they lack sufficient faith to escape. Some quote Job 3:25: “what I fear befalls me, and what I dread overtakes me,” as if Job’s fear brought these events on him. But Job probably refers to his present fears; he had reasons for posttraumatic (or in this case, during-trauma) stress. Compare Job’s lament about how unexpected his sufferings were: “When I expected good, then evil came; When I waited for light, then darkness came” (30:26, NASB). Part of the point of the book is that Job did not do anything (1:1)—or neglect anything (cf. 1:5)—to deserve his suffering. God himself declares this: “Have you considered my servant Job? There is no one like him on the earth, a blameless and upright man who fears God and turns away from evil” (1:8, NRSV).

When brothers and sisters suffer, let’s mourn with those who mourn (Rom 12:15), like members of one body who suffer together (1 Cor 12:26). Mystery can be difficult from the standpoint of theodicy or apologetics. Scoffers may complain, “Where is their God?” (cf. Ps 42:3, 10; 79:10; 115:2; Joel 2:17). But while we do our best to honor him, God is able to defend his own honor, and he owes no answers to scoffers. Sometimes, in this life, he does not even explain himself to us.