Jesus had taken his disciples into Gentile territory to get away from the crowds (Mk 7:24). Even if Jesus temporarily escaped the paparazzi and the tabloids, however, he was too popular to fully evade notice; he could not even take his disciples on a private retreat without someone finding him. A woman had a desperate need, so desperate that she didn’t care that Jesus was on vacation; she needed deliverance for her daughter.

Aside from the fact that she was interrupting Jesus’s down time, she was, worst of all, a Gentile. And not just any Gentile: she was a Syrophoenician. Jesus was in the region of Tyre in Phoenicia; Jesus’s disciples would know Phoenicia as the region where wicked Jezebel was from—though also the region of a woman who had received the prophet Elijah. Mark identifies this region as Syrophoenicia, to distinguish it from the Phoenician colonies in north Africa (founded after the time of Jezebel).

Jesus had just been teaching his disciples that outward ritual purity is not what matters (7:1-23). That theme sheds some light on his interaction with the Gentile woman here.

Mark also tells us that the woman was a “Greek” (literally in Mark 7:26, though some translations more blandly proclaim her a “Gentile”). That is, she not only lived among descendants of the ancient Phoenicians, but she also belonged to what had been the ruling citizen class since the time of Alexander the Great. She belonged to the privileged class that often maintained its wealth by exploiting the poorer farmers in outlying areas, both Phoenician and Jewish.

Now, however, this elite woman is desperate. Another Gospel indicates that the disciples wanted Jesus to send her away (Matt 15:23), just as they tried to keep young children or others tried to keep a blind beggar from imposing on Jesus (Mark 10:13, 48), just as a disciple once tried to protect Elisha from interruptions (2 Kgs 4:27). But this woman remains persistent. Although we cannot read too much into verb tenses, it is possible that the Greek imperfect verb tense might indicate that she not only asked Jesus to deliver her daughter, but kept pestering him. Certainly, Matthew is clear that she refuses to be put off (Matt 15:22-25).

Jesus, however, puts her off, insisting that his mission is to the “children” first, i.e., to God’s people; the children’s bread should not be thrown to the dogs. This woman belonged to a social class that had been consuming other people’s bread, taking food from other children’s mouths, for a long time. Now desperation had forced this member of the elite to humble herself and plead for help from a Jewish teacher—and he humiliates her even more! Calling someone a dog back then, whether of the male or female variety, meant essentially what it means today. It was one of the most grievous insults of antiquity, and while Jesus does not directly call her a dog (he simply makes a comparison), she could have taken offense and left.

She, however, is too desperate to give up. She humbles herself yet further, and construes Jesus’s image the way it could be applied in her Gentile environment. In her Gentile setting, people sometimes had pet dogs, and of course messy children dropped crumbs. She doesn’t need to be treated as an Israelite; Jesus’s power is so great that even the leftover crumbs from the table will be enough to deliver her daughter (Mark 7:28). Jesus counts her persistence and humility as faith, and answers her request (7:29-30).

The way Jesus treats this woman fits many of Mark’s surrounding narratives. Desperate to get help from the only one who can heal their friend, four men tear up a roof to get their friend to Jesus. Jesus calls this insistence “faith” (Mark 2:5). A woman with a flow of blood can make ritually impure anyone she touches or anyone whose clothes she touches (Lev 15:25-27). Nevertheless, yet she has to get to Jesus. She presses her way through the crowds and touches Jesus’s garment, with an expression of scandalous faith (Mark 5:25-34). Jesus invites her to testify publicly of her healing, even though in the eyes of the crowd, her act had made Jesus impure for the rest of that day. Jesus is not ashamed to be identified with us in our brokenness, so that he might make us whole. People try to keep blind Bartimaeus from Jesus, but he will not let anything keep him from Jesus (Mark 10:47-48).

Do you see the pattern? Many of the people who needed help from Jesus faced one barrier or another. But when they faced the barriers or things went wrong, they did not give up. Like the Syrophoenician woman, they recognized that Jesus was the only answer to their need, and they would not let anything keep them from getting to Jesus. Like the farmer or merchant in Jesus’s parables of the treasure in the field or the pearl of great price (Matt 13:44-46), they recognized that Jesus was worth so much that they would give up everything else to have him and what he offers.

When things go wrong, do we simply shrug and give up, feeling like God is far away? Or do we persist in faith, trusting God no matter what? Even if his answer is delayed, or even if we do not get the particular blessing we seek, there is a blessing for those who hold firm in faith. Jesus is worth everything. Do not let any problem, anyone’s disapproval, or even what seems a divine rebuff itself, distract you from pressing in and seeking God with all your heart.

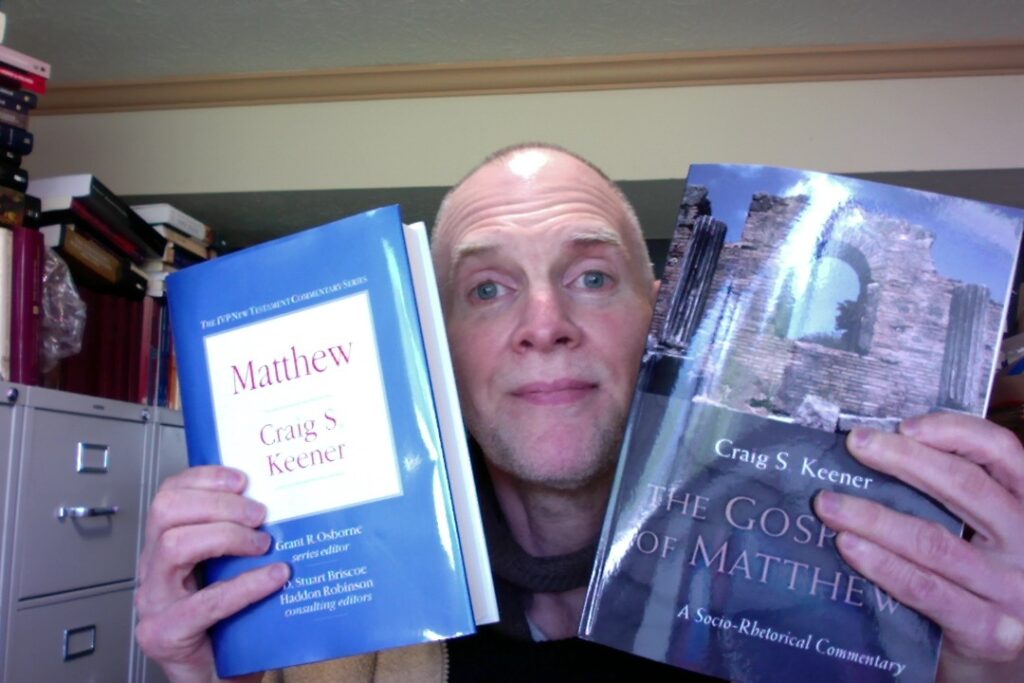

Craig S. Keener is professor at Asbury Theological Seminary and the author of many books, including Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts (Baker Academic), and two commentaries on Matthew’s Gospel.