apologies… this is akin to the argument of an island greater than which none can be conceived …

Category Archives: Theology

Live for eternity

32-second video

It’s simple math: what’s most important is what counts forever. And what counts most with God is what He gave His Son for: people’s lives.

What is Humility? (15-second video)

Humility is knowing who God is and who you are …

What is Holiness? (18-second video)

Loving God so much that nothing else matters compared to him …

Is Faith a Leap in the Dark? (18-second video)

Believers can have faith because God is FAITHFUL.

Your religion can’t save you

If you rest your eternal hope in taking the Eucharist/Lord’s Supper …

If you rest your eternal hope in having once repeated a prayer of conversion …

If you rest your eternal hope in excited feelings when you sing …

If you rest your eternal hope in your church membership or denomination …

You rest your hope in something that cannot help you.

But if you rest your hope in Jesus, including a Jesus you have met in any of these or other ways, then you are my brother or sister.

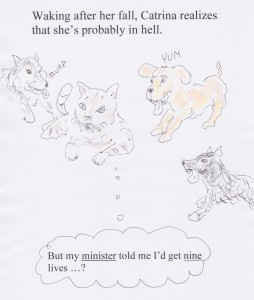

Cat hell (cartoon)

Abram’s Growing Faith—Genesis 15—16

We rightly think of Abraham as our ancestor in faith, but his faith began small, just like all of ours. The faith necessary for God to count him righteous (Gen 15:6) was much less than the extraordinary faith demonstrated when he offered up Isaac years later (22:3). Abraham’s faith, like ours grew over the years. It was not something that he worked up by the strength of his will or by fertile imagination; it grew in response to witnessing God’s faithfulness over the years. He learned increasingly more deeply that God can be trusted, and he learned this because he had a relationship with God, where God spoke clearly and Abraham obeyed fully.

God had already promised Abram a seed (indeed, a “great nation,” 12:2a) and a land (12:1e). In 15:2, however, when God promises Abram a reward, Abram balks. What reward can count, since Abram is childless? He cannot pass on any of his blessings to his children; they will go instead to his leading servant (15:2-3). (In Mesopotamian custom, however, a designated heir could be displaced if the testator subsequently had a son.) Abram is not expecting a “great nation” to come from him, at least not genetically.

Yet God renews the promise, and affirms innumerable descendants for Abram (15:5). Keep in mind that Abram is now between 75 and 85 years old (12:4; 16:3, 16), Sarai is just ten years younger (17:17), and that they have had no children yet. (In fact, even when Abraham sees the promise fulfilled, there will be just one son of promise, who will also have just two sons himself.) Yet Abram believes that God will give him innumerable descendants (15:6a). This is significant faith, not unlike the act of faith Abram undertook when he left everything familiar to him in obedience to God’s call (12:4). Still, this faith has yet to be tested over time.

God counts this faith of Abram’s as righteousness (15:6); we obey (as in 12:4) because we believe God’s promise, so our most fundamental response to God, which he accepts, is trusting his Word, depending on what he says. But what immediately follows this beautiful expression of intimacy between God and Abram? God has assured Abram about his seed, and now assures Abram about the land; God’s plan is to give him the land to possess it (15:7). “How will I know that I will possess it?” Abram asks (15:8). This may not be doubting God’s word per se; he may simply wish to know how he can be sure that he will meet the conditions if the prophecy is conditional. But it seems that he is asking for a confirmation.

God grants him a visionary dream that promises him the land, although also showing the difficulties that his descendants will experience before that vision is fulfilled (15:9-16), essentially summarizing the first part of Exodus. God confirms this promise by entering into a clear covenant with Abram (15:17-21), even accommodating contemporary expectations for covenant sacrifices and meals. God comes down to Abram’s level to assure him.

But Sarai does not have children (16:1), and by Genesis’s chronology, she is roughly 75 years old (cf. 16:16; 17:17). Thus, following Mesopotamian custom among wealthy households, Sarai urges Abram to use Hagar, Sarai’s servant, as a sort of “surrogate mother” (as Renita Weems has put it) to bear a child in Sarai’s name (16:2-3). (As an Egyptian, Hagar was probably a servant given to Sarai and her family during their stay in Egypt; cf. 12:16, 20.) Childbearing and heirs were essential priorities in their milieu, and while God had promised Abram descendants, he had not specified that they would come physically through Sarai.

Why does the narrative about Hagar immediately follow God’s reaffirmation of his promises to Abram? Perhaps in part to show us the difficulty of understanding God’s purposes more fully even when he has spoken a few of the details to us; and perhaps also to illustrate that Abram’s faith in Gen 15:6 was just rudimentary faith, compared to the sort of faith Abram would exhibit in Gen 22.

The faith that it takes to be justified is rudimentary: we simply need to take God at his word that he has promised, namely, that he has provided us salvation by Jesus’s death and resurrection (Rom 4:22-25). That is, it is not difficult to exercise faith for salvation.

But as we continue to walk with God and persevere through tests of our faith, we grow to see that God is reliable and that even in the hardest times there is hope. Abraham had seen God provide him a son miraculously and believed that this same God would fulfill his promise if Abraham obeyed him fully (Heb 11:17-19). We may not always hear the details as clearly as Abraham did, but we have surely heard the message of the cross. God is trustworthy, and tests of our faith are opportunities for us to learn faith in a deeper way, beyond saving faith. We may learn, ever more deeply, that God is trustworthy; if we persevere, the hardest challenges to faith are the ones that ultimately drive home his faithfulness most deeply, because no matter what God still has a plan and purpose for us that lasts forever.

(This is part of a series of studies on Genesis; see e.g., Sodom; flood; creation; fall; God’s favor.)

Paul and the Law

Scholars articulate a range of views concerning Paul’s approach to the law. A basic summary of my own current perspective (which surfaces at points in my small 2009 Romans commentary) might be as follows:

- Paul respects the law as God’s Word; this includes both the narrative and the legal material.

- Paul believes that the law was meant to teach right behavior (much of which is universal, though Paul does not usually spell out the hermeneutic that guides how he distinguishes those elements).

- Paul does not believe that the law was meant to transform the heart directly; rather it is meant to point/testify to the experience with the law’s God that transforms the heart.

- The law’s specific stipulations guided Israel in their setting (e.g., agrarian, in the promised land, etc.), but just as those stipulations required new forms of obedience for their day, so the fuller revelation in Christ takes on new forms.

- This fuller revelation in Christ, which Paul has undeniably experienced, has inaugurated (albeit not consummated) the promised messianic reign in a largely unexpected way (most dramatically, in a cruciform way), with equally unexpected consequences.

- This fuller revelation in Christ makes available (as a foretaste of the coming world) the life-transforming experience with God through the Spirit that fulfills all the principles of the law (thus, for example, the new covenant’s greater circumcision of the heart to which earlier physical circumcision merely pointed; or Jesus’s summary of the law’s heart as love).

- The law’s universal moral and spiritual principles, which God communicated to Israel in a specific context, can be recontextualized by the Spirit for all people of the new covenant, including ethnic Gentiles grafted into Israel’s heritage through following Jesus, Israel’s Messiah (here it must be acknowledged that we often lack consensus on what the universals are; I have offered elsewhere suggestions for discerning those; see e.g., http://www.craigkeener.org/how-i-love-your-law-ot-laws-in-context/; http://www.craigkeener.org/understanding-and-applying-ot-laws-today/; http://www.craigkeener.org/which-day-is-the-sabbath/).

- The law testifies to the way of a personal relationship with God, as evidenced in the lives of Abraham, Moses, and others; its heart is more about God and his covenant love (e.g., Exod 34:4-7) than about its stipulations (though those stipulations remained crucial as part of God’s covenant with Israel at Sinai).

- As part of Israel’s heritage and a continuing witness to the universal truth the Scriptures convey, even many of the law’s traditional stipulations remain valuable to those who remain Jewish by ethnic identity (e.g., Messianic Jews, such as Paul himself was, are fully within their rights to continue to express their Jewish heritage in this way).

- Paul believes that to approach the law as a list of duties (even ones joyfully undertaken) rather than a witness to the way of faith in (and thus personal relationship with) God (Rom 3:27; 9:31-32), or apart from the enabling experience of the Spirit (8:2), cannot transform the identity (more controversially, I am inclined to add, “and never could”; I believe that Paul saw Deut 30 and other parts of the law testifying to divine rather than human transformation of those who walk with God, with the new covenant developing this transformative empowerment more deeply in light of Jer 31:31-34 and Ezek 36:25-27).

- Treating the law’s stipulations as a means of demonstrating righteousness instead of depending on the divine favor and empowerment to which the law pointed in fact defies dependence on God’s favor and hence incurs condemnation. In this way, the law can even function as an instrument of divine judgment to those who miss God’s heart there.

Now, if you can figure out what such a set of views should be called, you are smarter than I. There are so many different permutations on various details on the scale between Luther and various New Perspective(s), with Reformed articulations often friendlier to continuing value for the law than some other views (especially Bultmann’s), that I find traditional ways of classifying views inadequate (even if they are necessary to provide some sort of handle on the spectrum).

I am noting this hastily constructed list because I am turning more of my attention back to Pauline studies now, and if I am wrong on some of these points, it will be helpful for me to learn that now before I publish more work on this subject! Nevertheless I remain certain that, given the range of perspectives now current on various details, there is almost no way to summarize a view without missing some nuancing valuable for this or that point of debate. For that I can only apologize in advance and hope to keep learning.

The faithless prayer meeting in Acts 12

2.5 minutes from Acts scholar Craig Keener.

For 23 free lectures on Acts, see http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/DigitalCourses/00_DigitalBiblicalStudiesCourses.html#Acts_Keener