Some biblical theology of leadership, provided by Jesus. One of the two models is that of Jesus’s own ministry:

Category Archives: Mark

Two kinds of leaders—Mark 10:42-45

I’m going to talk about two kinds of leaders in Mark 10:42-45, but the discussion will make fullest sense if I spend some time in the rest of Mark’s Gospel setting the stage for this.

Jesus throughout Mark’s Gospel displays one kind of leadership. Some scholars like to play Jesus’s “Messianic secret” (his invoking silence regarding much of his ministry) off against his signs or glory. But they are envisioning the wrong dichotomy. Throughout the Gospel, Jesus is healing and delivering others, even at risks to himself. (His times with the marginalized would not commend him to the elite.) He is not seeking his own honor; his acts of healing are part of his being a servant to others. Jesus spent time with the disabled, and moral and social outcasts—he’s not looking to get the powerful to back his cause.

There are also other kinds of leaders in Mark’s Gospel. These include some of the scribes and Pharisees, whose confrontations with Jesus show them more committed to their stringent interpretations of Scripture than they are to the desperate human needs Jesus is meeting. Still more unlike Jesus are the Jerusalem elite, who flaunt and sometimes abuse their honor and power. Like tenants in the vineyard in the parable Jesus tells in Mark 12, these leaders forget that God allowed them to be caretakers. They do not want to relinquish their power over the vineyard of God’s people.

We should expect the disciples to be different. Jesus is training these relative nobodies to be leaders in his kingdom. Most of them are from modest or poor backgrounds; most of them were also probably not well-educated (although at least the tax collector should have had basic writing literacy). They were Galileans, whom Jerusalemites sometimes viewed as country bumpkins. They should understand that Jesus is about helping those in the greatest need, not about self-exaltation.

But soon the disciples, expecting places of honor in Jesus’s kingdom, begin looking like the other kinds of leaders rather than like Jesus. They try to protect Jesus from being bothered by children (10:15); other followers want to protect him from a blind beggar (10:48). After the disciples try to keep away the children, Jesus has to repeat a lesson he had already given his disciples about receiving children (9:36-37; 10:14-15)!

And before the lesson of 10:42-45, they become even deafer to Jesus’s message. After a rich man refuses to surrender his wealth for the kingdom, Jesus again reminds his disciples that the first will be last (10:31) and that Jerusalem’s elite will precipitate his death (10:33-34). Instead of contemplating this sobering warning, James and John immediately ask to be greatest in the kingdom (10:35-40). (After all, they were just on the Mount of Transfiguration with him and Peter, while the other disciples were failing in an exorcism below the mountain.) This ploy makes angry the other ten: James and John are butting ahead of them in line (10:41)! The disciples had already been debating among themselves who was the greatest, and Jesus had already responded that the greatest would be like a child (9:33-35). His message, however, has obviously not yet sunk in.

So Jesus gives the lesson in 10:42-45. Here he contrasts two forms of leadership. For the first, he speaks about the world’s way of power, exemplified by the “rulers of the gentiles” (10:42). (Keep in mind that, for Jesus’s Galilean disciples, gentiles did not exactly epitomize moral ideals.) This was the sort of raw power that allowed Pilate to hand Jesus over for execution or for the Jewish tetrarch Herod Antipas to have John beheaded (though both Pilate and Herod succumbed to others’ demands in these cases). By Galilean standards, Herod even seemed a “king” (6:14, 22, 25-27).

This differed from the ideal kind of rulership, the reign of God, his kingdom, proclaimed by Jesus (1:15). This divine kingship would someday be manifested in the glory that God’s people were expecting (14:25; 15:43), but it first came in a hidden way—the humble “secret” or mystery of the kingdom I’ve already mentioned (4:11-12). It is a kingdom that belongs to children (10:14-15), inimical to power based on wealth (10:23). And the language of king, besides the pseudo-king Herod, clusters in Mark 15, when his enemies mock Jesus as king of the Jews (15:2, 9, 12, 18, 26, 32) and crown him with thorns (15:17).

The rulers of the gentiles exercise authority in self-seeking, abusive ways (10:42). By contrast, Jesus exercises authority not like the scribes (1:22), but for driving out demons (1:27) and forgiving sins (2:10). He delegates this authority to his disciples—also to drive out demons (3:15; 6:7), waging war against the enemy kingdom of Satan (3:24-27).

In contrast to the power of gentile rulers (10:42), Jesus offers a contrasting paradigm (10:43-44). “This way of the gentiles—that’s not how it must be among you. Instead, whoever wants to be great among you will be your servant, and whoever wants to be first among you will be slave [doulos] of all” (10:43-44).Jesus uses power to heal the sick (5:30), not to help himself (15:30, 32; cf. Matt 4:2-4).

Unfortunately, this is not the first time Jesus had had to offer this lesson: he has to keep reminding them! In 9:33-34, the disciples had been discussing who was the greatest among them. Jesus then warned them in 9:35 that whoever wants to be first will be last and servant of all. Now again James and John had sought to be highest in the kingdom, and Jesus has had to repeat the lesson. Our habit of competing for honor or attention dies hard.

Yet Jesus is not offering mere abstract instruction. He is offering himself. And insofar as he is our hero, our model of greatness, humbling ourselves must become our ambition! Our Lord is greatest of all, having humbled himself most of all: though being divine, he humbled himself, taking on him the form of a servant, and became obedient to death, even the particularly shameful death on a cross—the ultimate humiliation. Yet God has exalted Jesus Christ as Lord of the universe! (Phil 2:5-11).

And so Jesus gets specific, in 10:45 essentially adding another passion prediction that brings them back to the subject that preceded the quest for greatness (10:33-34): Jesus, the Lord himself, must die. “For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many.”

Mark’s entire Gospel shows Jesus serving, a servanthood that climaxes in Mark’s lengthy passion narrative. “Ransom” (10:45) often meant the price used to buy someone from slavery. Jesus by his own life offers himself as a slave (10:44) to free us from slavery. We could not have saved our own lives for eternity, but Jesus does. In 8:37, Jesus asks what a person can give in exchange for their soul (antallagma psuchê). Here Jesus says that he gives his own life (psuchê) in the place of (anti) many. He gives his life in exchange for ours.

We whom God had graciously appointed as leaders—some of us from lowly backgrounds like the disciples—have a special privilege and opportunity to serve all the more. May we always remember our Lord’s model: for how can we ever serve as humbly as he has served us?

The children’s bread and dogs’ crumbs—Mark 7:24-30

Jesus had taken his disciples into Gentile territory to get away from the crowds (Mk 7:24). Even if Jesus temporarily escaped the paparazzi and the tabloids, however, he was too popular to fully evade notice; he could not even take his disciples on a private retreat without someone finding him. A woman had a desperate need, so desperate that she didn’t care that Jesus was on vacation; she needed deliverance for her daughter.

Aside from the fact that she was interrupting Jesus’s down time, she was, worst of all, a Gentile. And not just any Gentile: she was a Syrophoenician. Jesus was in the region of Tyre in Phoenicia; Jesus’s disciples would know Phoenicia as the region where wicked Jezebel was from—though also the region of a woman who had received the prophet Elijah. Mark identifies this region as Syrophoenicia, to distinguish it from the Phoenician colonies in north Africa (founded after the time of Jezebel).

Jesus had just been teaching his disciples that outward ritual purity is not what matters (7:1-23). That theme sheds some light on his interaction with the Gentile woman here.

Mark also tells us that the woman was a “Greek” (literally in Mark 7:26, though some translations more blandly proclaim her a “Gentile”). That is, she not only lived among descendants of the ancient Phoenicians, but she also belonged to what had been the ruling citizen class since the time of Alexander the Great. She belonged to the privileged class that often maintained its wealth by exploiting the poorer farmers in outlying areas, both Phoenician and Jewish.

Now, however, this elite woman is desperate. Another Gospel indicates that the disciples wanted Jesus to send her away (Matt 15:23), just as they tried to keep young children or others tried to keep a blind beggar from imposing on Jesus (Mark 10:13, 48), just as a disciple once tried to protect Elisha from interruptions (2 Kgs 4:27). But this woman remains persistent. Although we cannot read too much into verb tenses, it is possible that the Greek imperfect verb tense might indicate that she not only asked Jesus to deliver her daughter, but kept pestering him. Certainly, Matthew is clear that she refuses to be put off (Matt 15:22-25).

Jesus, however, puts her off, insisting that his mission is to the “children” first, i.e., to God’s people; the children’s bread should not be thrown to the dogs. This woman belonged to a social class that had been consuming other people’s bread, taking food from other children’s mouths, for a long time. Now desperation had forced this member of the elite to humble herself and plead for help from a Jewish teacher—and he humiliates her even more! Calling someone a dog back then, whether of the male or female variety, meant essentially what it means today. It was one of the most grievous insults of antiquity, and while Jesus does not directly call her a dog (he simply makes a comparison), she could have taken offense and left.

She, however, is too desperate to give up. She humbles herself yet further, and construes Jesus’s image the way it could be applied in her Gentile environment. In her Gentile setting, people sometimes had pet dogs, and of course messy children dropped crumbs. She doesn’t need to be treated as an Israelite; Jesus’s power is so great that even the leftover crumbs from the table will be enough to deliver her daughter (Mark 7:28). Jesus counts her persistence and humility as faith, and answers her request (7:29-30).

The way Jesus treats this woman fits many of Mark’s surrounding narratives. Desperate to get help from the only one who can heal their friend, four men tear up a roof to get their friend to Jesus. Jesus calls this insistence “faith” (Mark 2:5). A woman with a flow of blood can make ritually impure anyone she touches or anyone whose clothes she touches (Lev 15:25-27). Nevertheless, yet she has to get to Jesus. She presses her way through the crowds and touches Jesus’s garment, with an expression of scandalous faith (Mark 5:25-34). Jesus invites her to testify publicly of her healing, even though in the eyes of the crowd, her act had made Jesus impure for the rest of that day. Jesus is not ashamed to be identified with us in our brokenness, so that he might make us whole. People try to keep blind Bartimaeus from Jesus, but he will not let anything keep him from Jesus (Mark 10:47-48).

Do you see the pattern? Many of the people who needed help from Jesus faced one barrier or another. But when they faced the barriers or things went wrong, they did not give up. Like the Syrophoenician woman, they recognized that Jesus was the only answer to their need, and they would not let anything keep them from getting to Jesus. Like the farmer or merchant in Jesus’s parables of the treasure in the field or the pearl of great price (Matt 13:44-46), they recognized that Jesus was worth so much that they would give up everything else to have him and what he offers.

When things go wrong, do we simply shrug and give up, feeling like God is far away? Or do we persist in faith, trusting God no matter what? Even if his answer is delayed, or even if we do not get the particular blessing we seek, there is a blessing for those who hold firm in faith. Jesus is worth everything. Do not let any problem, anyone’s disapproval, or even what seems a divine rebuff itself, distract you from pressing in and seeking God with all your heart.

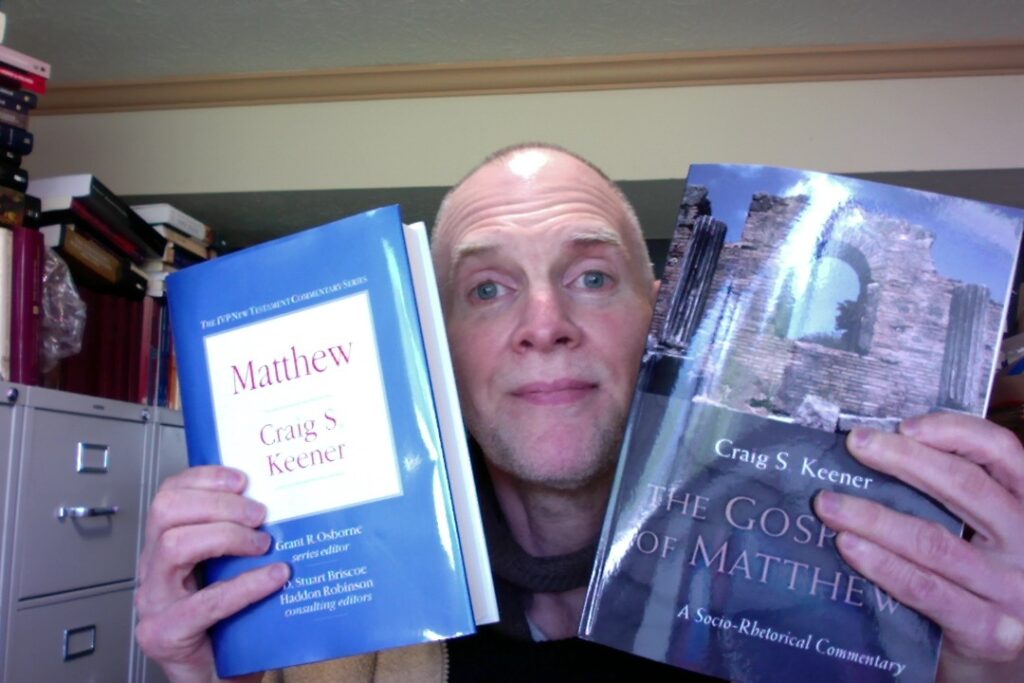

Craig S. Keener is professor at Asbury Theological Seminary and the author of many books, including Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts (Baker Academic), and two commentaries on Matthew’s Gospel.

He came to change from the bottom up

“You know that those who are considered rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. But it is not so among you; but whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first among you must be slave of all. For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.”—Jesus, in Mark 10:42-45 (adapted from NRSV, NIV and ESV)

In imperial propaganda, the emperor was simply the princeps, “the first” (see 10:44); but while he lavished benefactions on the Roman people, he was no one’s slave (10:43), and no Roman hearer could exclude the emperor from the verdict of 10:42. The contrast with 10:45 was an absolute ideological challenge to the dominant ideology of the empire—yet in a form that offered no threat of uprising (cf. 12:16-17). So long as elites were not compelled to believe it, they might welcome all the greater submission among those they considered foolhardy enough to embrace it.

Jesus came to change the world from the bottom up—not by power in human terms, but by humbly serving and dying for others. Who is ready to follow his example?

Jairus’s daughter and the woman with the flow of blood

One had been alive for twelve years; the other had suffered for twelve years. One grew up in a prominent household; the other was now destitute and socially marginal. Both had a desperate need, and Jesus met that need. Both Jairus (on behalf of his daughter) and the woman with the flow of blood become models of faith in this story.

I give more details in a web article that Christianity Today asked me to write this week, here. Because of our miscarriages, my wife and I have experienced grief over the loss of children, though not children that we had spent years raising. But we can also celebrate the miracles that God does. We can learn from the faith of these two individuals in Mark 5, when called to trust Jesus for a miracle; we can also learn from the faith that the disciples should had (but didn’t) in the face of suffering, later in the Gospel. And we all can celebrate the hope that the gospel provides.

Jesus and elites

Why did Jesus keep running into trouble with elites? The scribes, an educated elite, are judging him in Mark 2:6-7, 16, and the Pharisees, a pious fellowship honoring ancestral tradition criticized him in 2:24 and 3:6. Jesus answers evasively and in riddles and parables designed to delay harsher confrontations till the closing phase of his ministry. In 3:22, Jerusalemite scribes accuse him of acting by Satan; although Jesus still reasons with them, his response escalates to a serious warning. Jesus responds more harshly to the challenges of scribes and Pharisees in 7:6-13, even calling them hypocrites. (In 7:5, as in 2:24, they criticized his disciples, inviting his defense. In 10:11-12, Jesus defends innocent parties divorced by their spouses.)

Jesus’s forerunner, John, suffers under a different elite: the political ruler of Galilee, the tetrarch Herod Antipas, who executes him (6:27).

Yet Jesus also warns his followers against acting like religious elites themselves. When his followers want to exclude someone who acts in his name because the person does not belong to their own group, Jesus stands up for the person (9:38-42). When his followers want to protect Jesus from interruptions by “unimportant” people like little children or blind beggars, Jesus reaches out to those “unimportant” people (10:13-16, 48-52). When some disciples want to become most prominent in the kingdom, Jesus reminds them that true leadership ought not to reflect the world’s ideals of power, but servanthood (10:35-44). Our Lord himself modeled this, coming to serve and to die for us (10:45).

Naturally Jesus’s conflict with elites escalates in the region’s elite location, Jerusalem. He fends off challenges from critics in ch. 12 and reveals coming judgment on the temple (and thus the religious establishment that claims to speak for God) in 13:1-2. And finally the chief priests, who doubled as Judea’s aristocratic leadership, hand Jesus over to the Roman governor for execution. Jesus had already hinted as much in his parable in 12:1-11, where he depicted Jerusalem’s leaders as abusing their rule over God’s people.

Jesus welcomed everyone, but he went out of his way for the lowly, not the rich (10:17-25) and powerful. To the extent that any of us have some social advantages in life, to that extent we must humble ourselves all the more to approach Jesus; it is harder for the wealthy to enter the kingdom (10:23) and easier for children (9:35-37; 10:14-15). If we want to follow our Lord’s example, we need to humble ourselves. When we live by the world’s values of celebrity cults and seeking power over others instead of being servants to all, we miss the very point for which our Lord called us.

How much is eternal life worth?—Mark 8:34-38

“If anyone wants to follow after me, let one deny oneself and pick up one’s cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it; but whoever will lose their life for my sake and the gospel’s will save it! For what good is it for someone to gain the whole world at the expense of one’s life? For what should someone give in exchange for their life? For whoever is ashamed of me and my words in this adulterous and sinful generation, of that person the Son of Man will be ashamed when he comes in his Father’s splendor with the holy angels!”—Mark 8:34-38

Toward the beginning of his Gospel, Mark provides what looks like a model (1:16-20) of embracing Jesus’s preaching about the kingdom (1:15). Prospective disciples abandon their livelihoods and leave behind families to follow Jesus. So far, so good: they count Jesus and his kingdom as worth more than possessions and other relationships. But whether they truly value Jesus and the kingdom more than their own lives (cf. Luke 14:26) remains to be seen.

Jesus’s disciples immediately (euthus)“abandoned” (aphientes) their nets to follow him (Mark 1:18); though not using the same Greek term, others also left behind their livelihoods to follow Jesus (2:14; cf. 10:50-52). Peter reaffirms that they left everything to follow Jesus (10:28-29). But in 14:50, when following Jesus may entail sharing his cross, they all abandon (aphentes) Jesus and flee. They are in such haste to flee that, despite Judean abhorrence of nakedness, one leaves his outer cloak in his potential captors’ hands in haste to escape (14:51-52). They were willing to forsake other things, but not life itself (8:34-38).

Jesus had warned them; his disciples would stumble (skandalizô, 14:27); Peter, however, insisted that he would not stumble (skandalizô, 14:29). Jesus warned that true disciples must deny themselves (8:34), but that Peter would deny Jesus (14:30; fulfilled in 14:72). Peter insisted that he would never deny Jesus (14:31), but perhaps underestimated the power of the fight-or-flight response of his nervous system; he and his colleagues had been afraid before (4:41; 6:50; 9:32; 10:32), a reaction that should have been tempered by faith (cf. 5:36). Those who abandon other things for Jesus will receive rewards—but also persecutions (diôgmoi, 10:30).

Simon Peter, who insisted that he would never deny Jesus, should have been ready to take up Jesus’s cross (8:34); but his triumphalist theology that militated against suffering (8:31-33) left him unprepared, and Rome had to draft another Simon to carry Jesus’s cross (15:21). (Simon was the most common Judean male name, so this could be coincidence, but Mark might play on it anyway.)

Peter, whose name means “rocky,” acted, with the other disciples, like the rocky (petrôdes) soil in 4:16-17, who immediately (euthus)embrace the kingdom message joyfully—but when hardship (thlipsis) or persecution (diôgmos) comes, they immediately (euthus)stumble (skandalizô) from the way (4:16-17). Mark may use this as a warning for coming tribulation (thlipsis; 13:19, 24).

Disciples might be ready to fight the world’s way (14:47) or even follow “from afar” (14:54), but are we ready to follow to the cross? Do we design our theology for what we can get from Jesus, or are we loyal to our Lord for himself? Are we rocky soil, like the first disciples? Thorny soil, like the rich young ruler? Or will we be good soil, through whom the seed multiplies many times over through making other true disciples?

This would not be those disciples’ last chance (16:7), and we may still have other opportunities to show that we will be loyal to Jesus even in the face of a world that despises him (8:34). Insisting that we will never deny him is no guarantee that we will not. By contrast, learning to temper our fear with faith, with confidence in Jesus, helps prepare us for potential harder times ahead.

Misunderstanding Jesus’s kingship—Mark 15:16-20

“And the soldiers led Jesus away inside the courtyard of the palace (i.e., the governor’s headquarters), and they called together the rest of their unit. And they draped him in a purple robe, and weaving together a garland of thorns, they placed it on him. And they began applauding him: “Hail, King of the Jews!” They struck his head with a reed, spat on him, and knelt down as if to honor him as king. And when they were done mocking him, they stripped the purple robe from him and put his own clothes back on him. Then they led him out to crucify him.” (Mark 15:16-20)

In Mark 15, the kind of king the soldiers mock—one who flaunts power—is not the kind of king that Jesus is. Instead, his kingship corresponds to his very submission to suffering at their hands. This was a suffering to which his heavenly rank did not require him to submit; he submitted not out of obligation but on our behalf. Jesus models a different kind of authority than his mockers expected, an authority reliant entirely on God, and not from human rank.

This model fits the Lord’s mission throughout Mark’s Gospel. Jesus makes the lowly feel welcome, meeting their needs. But just as we would resent one child who bullies another, Jesus views harshly those who exploit or look down on the rest of his people. He challenges the wealthy priests, the proud leaders who run the temple, those who consider themselves intellectually or morally superior, those who revel in receiving respectful greetings, and so forth. Jesus ultimately pronounces judgment on the temple and its establishment, but with a wounded, broken heart.

Just as in the Hebrew Bible God laments the appointed shepherds who abuse his people (Ezekiel 34), Jesus confronts the religious and social leaders, who are the antithesis of what he is about. Their thinking, however, fits the way the world views status. Jesus’s heart breaks when even his own disciples, who are supposed to carry on the mission after him, don’t yet understand humility/servanthood.

Jesus wants to make sure, before he leaves, that his disciples won’t share his enemies’ valuations of power. He models living simply. He explains how the least are the greatest, and uses himself as an example (Mark 10:42-45). In the Gospel’s climax, he goes to the cross, submitting to persecution and death at others’ hands. Finally, after his resurrection, his disciples get it. Power over others is not something to seek! Rather, we must make ourselves servants, and depend on God’s power to use us.

How might our Lord’s model challenge those of us who are Christian leaders today? Jesus invites us to lead by looking out for the interests of the sheep, not our own interests.

Cf. Ezek 34:2, 11 (NET): “Son of man, prophesy against the shepherds of Israel; prophesy, and say to them–to the shepherds: ‘This is what the sovereign LORD says: Woe to the shepherds of Israel who have been feeding themselves! Should not shepherds feed the flock? … I myself will search for my sheep and seek them out.”

Mark 12:38-39 (NRSV): “As he taught, [Jesus] said, “Beware of the scribes, who like to walk around in long robes, and to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces, and to have the best seats in the synagogues and places of honor at banquets!”

Mark 6:34 (NRSV): “As [Jesus] went ashore, he saw a great crowd; and he had compassion for them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd”

Elijah in Mark 1:2

In Mark 1:2-3, Mark speaks of the messenger who prepares the way for YHWH. Mark links together two verses from the prophets addressing one who would prepare the way for YHWH’s coming. One is Malachi 3:1; the other isIsaiah 40:3. Mark may have learned the verses separately (cf. Matt 11:10//Luke7:27), but he follows good ancient Jewish interpretive procedure in linking verses that share a common theme, and especially common language. Both passages speak of one who will “prepare the way” of YHWH. (In their contexts, they share some other common wording; Isaiah’s “my messenger,” God’s own people, act as deaf and blind in Isa 42:19.)

Mark blends them so thoroughly that he names only the better-known prophet when he attributes them: Isaiah. This is helpful in focusing the reader’s attention on the larger context of this section of Isaiah, as noted in the preceding post on Mark 1:1.

But what about Malachi? Does Mark think at all of Malachi’s context? Malachi expects consuming fire when YHWH comes (Mal 3:2; 4:1), an expectation also held by John the Baptist in Matt 3:11//Luke 3:16. But Malachi returns to the preparer in Mal 4:5-6: this is the prophet Elijah, who will turn or restore people’s hearts, preparing them lest YHWH strike the land when he comes. (Jesus uses the Greek version’s term for “restore” for John’s mission as Elijah in Mark 9:12; it applies to Jesus’s healings in Mark 3:5 and 8:25.)

This verse prepares us to recognize John the Baptist as the promised preparer for YHWH. Sure enough, John is recognizable as Elijah in Mark’s introduction. He does not call down fire on his challengers or on a sacrifice on a mountain. What he does do is come at the Jordan (Mark 1:5), in the wilderness (Mark 1:4), and, most distinctively, wearing a leather belt around his waist (Mark 1:6). Elijah had ascended just past the Jordan (2 Kgs 2:6, 13), had spent time in the wilderness (1 Kgs 19:4), and, most importantly, is depicted specifically as wearing a leather belt around his waist (2 Kgs 1:8). However common or uncommon such belts may have been, the only passage in the Old Testament mentioning a leather belt is 2 Kgs 1:8, and the only passages in the New Testament mentioning it are those introducing John (Matt 3:4; Mark 1:6). Both use exactly the same two terms; this is the New Testament’s only use of the term translated “leather.”

Why is it so significant that John fills a role like Elijah? If John fulfills Malachi 3:1, then John prepares the way for YHWH. But Mark identifies John as preparing the way for the Spirit-baptizer (Mark 1:8), for Jesus. In the Old Testament, only YHWH may pour out YHWH’s own Spirit. Mark thus recognizes that Jesus is YHWH himself, the one who baptizes in the Spirit (Mark 1:8). Ergo: Jesus is Lord.

Good News about Jesus Christ and the introduction to Mark’s Gospel—Mark 1:1

Mark titles either his Gospel or its opening words with,“the beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, God’s Son.” So even a previously uninformed reader knows Jesus’s identity from the start, even as it unfolds only gradually in the narrative. It’s no surprise when the Father honors Jesus as his Son in Mark 1:11. What is more of a surprise for the uninformed reader will be how little his human contemporaries recognize him, and how the Gospel will climax in and elaborate the crucifixion of God’s Son.

“Good news,” or euangelion, applied to all sorts of things in Greek, but given Mark’s signaled interest in Isaiah in v. 2, it probably evokes the promised good news of Israel’s restoration emphasized there. In v. 3, Mark will note the herald of Isa 40:3 who prepares the way for YHWH, who leads his people through the wilderness in a new exodus, bringing them back to their land from exile and restoring them. Many Jews had resettled in the land, but they still awaited the full restoration of their people, along with the renewed creation God had promised (such as new heavens and new earth, Isa 65:17; 66:22). Isaiah goes on to speak of this way-preparing herald in terms of the remnant of God’s people, announcing good tidings to the rest of them (Isa 40:9, the standard Greek translation twice using the verb euaggelizô).

The next use of this verb in standard Greek translation of Isaiah appears in Isa 52:7, speaking of the messenger who “brings good news” (euangelizomenou) about peace for God’s people, who brings good news (euangelizomenos) involving salvation and God’s reign. In this context in Isaiah, this is good news that judgment has ended, and God is restoring his people. Isaiah 52:7 speaks of this as the good news, or gospel, of peace, of salvation, and of God’s kingdom.

That Mark wants to emphasize good news is clear because it frames Mark’s introduction. Mark treats John the Baptist as the optimum model of this herald, this way-preparer for YHWH, as he prepares the way for Jesus. (This should also let the biblically informed reader of Mark know something further about Jesus’s identity: he is YHWH.) But after John the Baptist’s arrest in 1:14, Jesus begins the public ministry that Mark’s Gospel addresses. Mark describes it this way: “Jesus came into Galilee, proclaiming God’s good news, by saying: ‘The time has been fulfilled! God’s kingdom has drawn near! Turn your lives around and depend on the good news!” (Mark 1:14-15).

That Mark’s understanding of this good news evokes Isaiah is also clear because of the mention of God’s kingdom, or God’s reign, as part of this good news (1:15). Remember Isa 52:7: part of this good news is, “Our God reigns.” Other Scripture praised God’s kingship as most evident in the conspicuous day of God’s justice (e.g., Ps 93:1; 96:10; 97:1; 99:1). It would be the kingdom that would shatter temporary earthly kingdoms with an eternal one (Dan 2:44), the kingdom of the Son of Man (Dan 7:14) and his people (7:18, 27). Jesus, too, places no trust in such temporary kingdoms and rulers (Mark 13:8-9).

Jesus uses “kingship” language to describe the content of his parabolic teaching (Mark 4:11, 26, 30; 9:47); it contrasts with the pseudo-royal governor of Galilee (6:14, 22-27) who executes God’s herald (6:27). Disciples see a foretaste of kingdom glory (8:38—9:1) in Jesus’s transfiguration (9:2). As Jesus enters Jerusalem, the crowds hail the promised kingdom of the Davidic king (11:10)—although they may overplay the Davidic part (12:37). Jesus announces to his disciples that they will share in the expected messianic banquet with him in God’s kingdom (14:25)—though separation between them must intervene.

Here we can begin to catch the irony of this “kingdom” from a human vantage point. But Jesus declares that this kingdom belongs to children (10:14-15) and to those who love their neighbor (12:34). He brings it not to prestigious and powerful people such as Herod Antipas, Jerusalem’s high council, Pilate, or to those proud of their wealth (10:23-25), but to people who are disabled (such as blind beggars), who are socially marginalized (such as tax collectors), and to others who are the antithesis of social prestige. (One prestigious person, Joseph of Arimathea, does somehow get the kingdom message closer to right than his colleagues; 15:43.)

But from here on out, Mark’s Gospel uses royal language almost exclusively in one way: for Jesus as the rejected king of his people, crowned with thorns and enthroned on a cross (Mark 15:2, 9, 12, 18, 26, 32, 43). We should have suspected as much, when already in the introduction the kingdom herald John was arrested (1:14), and in the last verse about “king” Herod Antipas Mark gets beheaded (6:27). The kingdom of this world was not ready to give up its worldly power.

Yet Jesus will return to Galilee to meet his disciples (16:7), so the preaching of the good news will start again, and spread among all nations (13:10), even in the face of hostility (13:9-11).

The fulness of the kingdom will come. Jesus’s signs of and teaching about the kingdom will prevail. But Mark is realistic about this world. This world’s kingdom’s will not surrender until the Son of Man returns (8:38; 13:26; 14:62). In Daniel, the reign of the Son of Man (the human one [Dan 7:13-14], contrasted with the preceding kingdoms depicted as beasts [7:3-8]) is linked with the triumph of the consecrated ones of the Most High (7:22, 27)—after suffering (7:21, 25). Let no one deceive you: suffering continues in this present age. But also let no one deceive you that this age is all there is. The fullness of our promised home is yet to come.