Some biblical theology of leadership, provided by Jesus. One of the two models is that of Jesus’s own ministry:

Category Archives: Social ministry. social justice

Ministry and the Marginalized—Luke 7:36-50

Luke wrote two volumes, the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts. His second book, the Book of Acts emphasizes the mission to the nations—a crucial mission without which we would not have Gentile Christians today (though we might at least have Messianic Judaism). But before recounting the mission to Gentiles in Acts, Luke prepares his audience by recounting Jesus’s mission to other kinds of outsiders in his first volume, the Gospel of Luke.

If we want to be ready for mission in another location, we can start preparing by crossing cultural and other barriers closer to home.

Throughout Luke’s Gospel, Jesus ministers to those lacking status and power in his culture (such as the poor and non-elite women). Among those alienated from society, he reaches out to “sinners”—those marginalized by virtue of their behavior. His kingdom does not depend on human political or military power; he pursues the lowly, showing that God is not impressed with our worldly credentials. Yet Jesus not only ministers to the marginalized; he builds his new kingdom around them.

Scripture often reports that God is near the lowly but far from the proud (e.g., Matt 23:12; Luke 1:52; 14:11; 18:14; Jms 4:6; 1 Pet 5:5); he reveals himself in human weakness more than in what the world deems power (1 Cor 1:18-26; 2 Cor 12:9; 13:4). Jesus welcomes everyone, but it is those who recognize their desperate need of him who most welcome him. If we recognize our need to depend fully on God, we are blessed. If we do not, we need to spend more time among the broken and the lowly, learning from their hearts.

In Luke 7:36-50, he welcomes the controversial gift that one such marginalized person offers.

It was considered pious to invite a popular sage over for dinner, and Simon the Pharisee has invited Jesus for dinner (Luke 7:36). At banquets, guests typically reclined on large, backless couches (three or four diners per couch), their feet pointed away from the tables; sometimes outsiders might come watch. A woman of ignoble repute in the community (so 7:37) enters the house and begins washing Jesus’s feet, wiping them with her hair. Simon is offended: surely a prophet like Jesus would know this woman’s ill repute. Indeed, in his culture respectable married women (i.e., respectable adult women) covered their hair in public. Thus by wiping Jesus’s feet with her hair, as far as Simon was concerned, the woman put her sinfulness on display!

But Jesus is indeed a prophet—he knows what Simon is thinking. Jesus helps Simon to realize that those who recognize their need for forgiveness most are the most grateful to receive it. Then Jesus, though still addressing Simon, turns away from the table to finally face the woman. Washing Jesus’s feet, she has been outside the circle of couches; banqueters reclined on their left elbows and their feet pointed away from the tables (after all, who wants someone’s stinky feet in their face?)

Jesus reminds Simon that he offensively failed to provide Jesus with the most basic, expected courtesies in their culture. A host should provide a guest water for washing the feet (though a respectable host would not wash the guests’ feet himself, a more servile task). Likewise, one should give a light kiss of respect to a teacher; one might also provide oil for anointing. Simon has failed in all these courtesies expected of a host. Jesus might be a special guest, but for Simon, Jesus is not that significant, compared to Simon and his peers.

By contrast, this woman has provided Jesus all the honors that Simon failed to offer—displaying gratitude for her forgiven sins. By linking forgiveness to their treatment of himself, Jesus implies that he himself is the bearer of divine forgiveness. By honoring or dishonoring him people show their response to grace.

Meanwhile, other table guests recoil in horror from Jesus’s words: how can he forgive sins (7:49)? They do not recognize how central Jesus is to God’s plan. They do not understand his identity. And, like Simon, they are proud, more ready to judge Jesus than to learn from him. All because he welcomes sinners!

When we look down on others who received grace after we did (perhaps the incarcerated, or unwed mothers, or even someone who wronged us personally), we forget that we, too, can be saved only by grace. Of course, Jesus is not offering cheap forgiveness to those choosing to remain in sin; he forgives those who truly turn to him. Yet this woman was turning from being a “sinner” more readily than the Pharisee and most of his guests were willing to turn from sinful, religious pride. To be most ready for crossing cultural barriers in mission (the Book of Acts), we should begin crossing barriers near us, to experience and share God’s grace (his generous favor) to others around us.

That Jesus welcomes the woman’s gift—no matter what others think—reminds us of another theme in Luke-Acts: those who are initially objects of mission can become missionaries themselves. For the most part, Jesus chose as his first agents fishermen, a tax collector, and those of apparently nondescript professions rather than the more humanly obvious choices of priests or scribes. Peter, the “sinful man” (Luke 5:8); Paul the persecutor (Acts 9:13-15); and others become agents of Christ’s mission.

The Spirit empowering the apostles’ circle for mission at Pentecost (Acts 1:8) is also poured out on the Samaritans (Acts 8:17) and Gentiles (Acts 10:44-47) and all who are far off (Acts 2:38-39). Why? So all these groups can share in the apostolic mission of proclaiming Christ. Some who may begin as some sort of marginal minority within our circle of believers may be laying the foundations for future ministry. Cheryl Sanders, a pastor and professor of ethics at Howard University, has a valuable book called Ministry at the Margins: The Prophetic Mission of Women, Youth & the Poor. Her title catches one of the themes in Luke-Acts.

God does not usually start his activity where we expect or the way we expect. He does not need our wealth, status or power, because he does not want our pride. He often starts with the lowly and the marginal (Luke 1:51-53), pouring out his Spirit and surprising us with revival, just to remind us all that the power for his work comes from him and not from ourselves.

Craig Keener is author of commentaries on Matthew, John, Acts, Romans, 1-2 Corinthians, Galatians, and Revelation; his IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament, has sold more than half a million copies.

What the Bible says about racial reconciliation (34 minutes)

As an interracially married minister, ordained in an African-American denomination but currently president of the Evangelical Theological Society, I want to share some of what the Bible teaches about ethnic conflict and reconciliation. This is just an overview (what I can do in half an hour), and I am skipping here my personal stories (again, staying at about half an hour). But my observations here draw on what I have been speaking about in my classes and public settings for some 30 years. Thirty years ago most people were not listening 🙁 but I am trying again today: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r1PcBRqFph0

(If you want a one-minute video with just some thoughts about racial reconciliation, from my wife Médine, who is from Central Africa, and myself, a white guy from the U.S., see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqQSUfbNeU0)

Pentecost Sunday and Race in the U.S.

Around the year 2000, for the Eerdmans Lectionary commentary, I wrote on a reading for Pentecost Sunday, on Acts 2. Here is one paragraph that I wrote:

“After recounting the proofs of Pentecost, Acts focuses on the peoples of Pentecost: Jewish people from many nations serve as the first representatives of the gospel crossing all cultural barriers (2:5-11). Some have compared the list of hearers here with the table of nations in Genesis 10, updated into the language of Luke’s day. If so, this passage may reverse the judgment on the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11: as God once scattered the nations by dividing their languages, he now empowers his church to transcend those divisions. One of the activities of the Spirit in the rest of Acts is guiding the church to cross cultural barriers beyond its comfort zones (8:27-29; 10:17-20; 11:12; 13:2, 4). An expositor could easily apply this example to racial reconciliation, cultural sensitivity, crosscultural ministry, global mission, and to church unity today (Rom 15:16; 1 Cor 12:13; Eph 2:18-22).”

My family is interracial (I’m the only white member; my wife and kids are black), so you can tell where I would take this if I were preaching this weekend. (At craigkeener.org, I usually focus on Bible study resources, but I responded with my personal convictions on my personal Facebook page shortly after the murder of our Christian brother George Floyd, because the issue just comes too close to home.)

But I think I can rightly hope that I am not alone on this. Given what’s happening in the U.S. right now (I write this on May 30, 2020), racial reconciliation is a burning topic. Nor is the issue a new one (I mentioned my earlier article to highlight this point). Minorities within a culture know the perspectives of the dominant culture, because such perspectives pervade the culture; the dominant culture, however, is usually far less acquainted with the experiences of minority cultures, because they can live life without having to recognize these experiences.

But as Christians, we belong to one body. It is incumbent on us—and especially for members of the dominant culture—to listen to and learn from the experiences of our brothers and sisters, to be “swift to hear, slow to speak” (James 1:19). Some may want to ignore the pain of our brothers and sisters, using as an excuse hooligans who exploit protests as an opportunity to loot. But what hurts Christ’s body pains Christ the head, and those whose first loyalty is Jesus, who care about his heart, must care for one another, and stand for justice for one another.

I also wrote some of the material on Pentecost for the forthcoming lectionary commentary from Westminster John Knox, where I elaborated more extensively on the implications of the transformation of Babel in Acts 2. There I concluded: “The Spirit in Acts thrusts us across human barriers to honor our Lord among all peoples. The Spirit also empowers believers together, regardless of ethnicity, class, gender, as partners in this mission, equally dependent on God’s enablement. Perhaps it is time, like the first disciples, to pray for the enablement of God’s transforming Spirit.”

For fuller detail on Acts 2, see Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (4 vols.; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012-15), 1:780-1038; or, more concisely, Craig S. Keener, Acts (Cambridge NT Commentary; Cambridge University Press, 2020), 121-78.

Jesus was a Refugee—Matthew 2:13-15

Among some, the claim that Jesus was a refugee has become politically divisive these days, so I should point out that the title used in this analogy predates the controversy; it was my own observation, published in my IVP Matthew commentary in 1997 (pp. 69-70). How that should apply to details of contemporary political debates may be a legitimate question. Whether Christians should care about refugees and try to help them is not. Whether Jesus and his family actually had to leave their country because of political oppression is a debate only among those who question the historical authenticity of Matthew’s report. Having prefaced my comments with these remarks, I turn now to the pre-controversy Bible study I wrote back in the early 1990s and have only slightly updated.

Persian Magi were known for using stars and dreams to predict the future, and it appears that on this one occasion in history, God spoke to the Magi where they were looking. Although Scripture forbade divination, in this period many people believed that stars could predict the future, and rulers anxious about such predictions sometimes executed others to protect their own situation. (One ruler, for example, is said to have executed some nobles to make sure that they, rather than he, fulfilled a prediction about some leaders’ demise!)

So large was the Magi’s caravan in Matthew 2 that they could not escape notice; Matthew says that all Jerusalem was stirred by their arrival. The Magi had every reason to assume that a newborn king would be born in the royal palace in Jerusalem; but despite Herod’s many wives, he had sired no children recently. Herod’s own wise men sent these Gentile wise men off to Bethlehem, just six miles from Jerusalem and in full view of Herod’s fortress called the Herodium. They later fled Bethlehem by night, but the disappearance of such a large caravan would not go unnoticed for very long.

Herod acts in this narrative just like history shows us Herod was: he was so paranoid and jealous that he had executed two of his sons on the (false) charge of plotting against him, as well as his favorite wife on the (false) charge of infidelity. On his deathbed, he would execute another son, and leave orders (happily unfulfilled) to execute nobles (so there would be some mourning when he died; cf. Prov 11:10). A probably apocryphal report attributes to the Roman emperor the opinion that it was safer to be one of Herod’s pigs than one of his sons.

Contrasting the different characters in this account reveals striking ironies. Fitting a theme in Matthew’s Jewish Gospel, these Gentiles come to worship Jesus. By contrast, Herod, king of the Judeans, acts like a pagan king: like Pharaoh of old (and another pagan king more recently), he orders the killing of male children. Most astonishing to us, though, should be Herod’s advisors, the chief religious leaders and Bible teachers of the day: they knew where the Messiah would be born, but unlike these Gentiles they did not seek him out. Merely knowing the Bible is no guarantee that we will obey its message. (We should note, however, that the Sanhedrin, whom Herod uses here as advisors, was not very independent in this period; he had executed his opponents and replaced them with his political lackeys.) As in the parable of the sower, we ought to sow on all kinds of soil; sometimes God has plans for the people we least expect.

But notice also the other characters. The narrative repeatedly emphasizes “the child and his mother” as the objects of Herod’s hostility. Though this powerful king will soon be dead, he feels threatened by those who were at the time politically harmless. Undoubtedly able to use the resources provided by the Magi, however, Joseph’s family found refuge in Egypt, like an earlier biblical Joseph. Probably they settled in the massive city of Alexandria, where according to some estimates nearly a third of the city was Jewish.

Years ago, when I wrote my first commentary on Matthew, I wrote at this point that Jesus was a refugee: a baby in a family forced to flee a corrupt dictator, just like so many political refugees in different parts of the world today.

As I wrote it, I grieved for my dear friend Médine, whose country, Congo-Brazzaville, was at war. Later I learned that her town had been burned down, and did not know for eighteen months if she was alive or dead; if she was alive, however, she was undoubtedly a refugee, along with perhaps as much as a quarter of her nation. Still later I discovered that she had fled the town carrying a baby on her back and joining others in pushing her disabled father in a wheelbarrow.

When Médine read in my Matthew commentary that Jesus was a refugee, she found meaning in what she had experienced; Jesus had suffered what she had suffered. Médine is now my wife, and we have a happier life. But we cannot easily forget those who, like our Lord two millennia ago, face suffering because of others’ injustice.

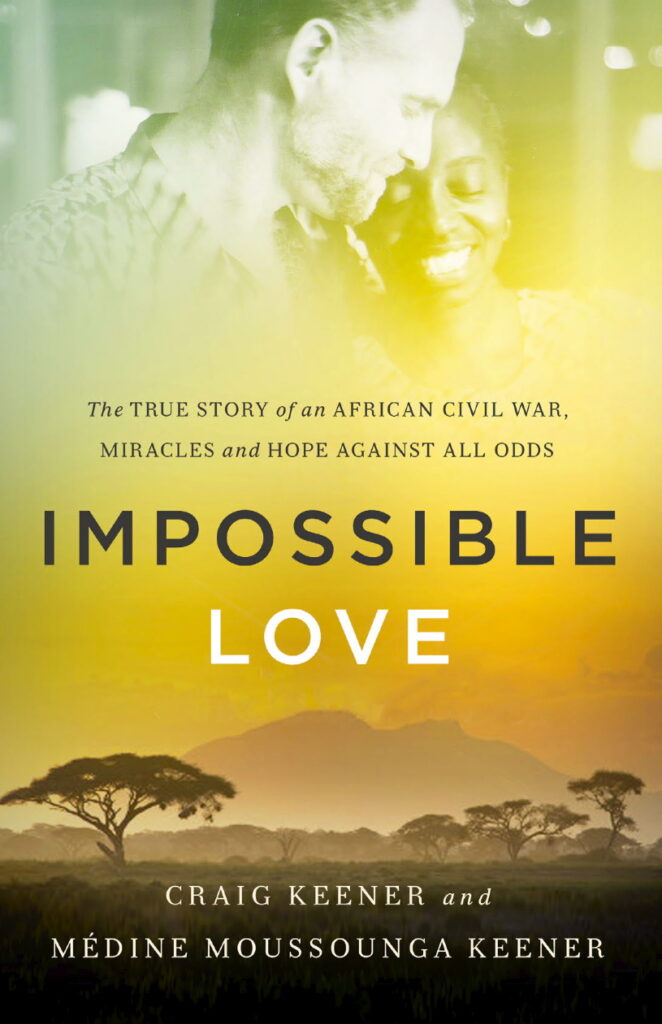

The story of Craig and Médine together appears in Impossible Love: The True Story of an African Civil War, Miracles, and Love Against All Odds (Chosen Books, 2016). Craig S. Keener is author of a smaller commentary on Matthew with InterVarsity Press and a larger one with Eerdmans (The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary, 2009), as well as The Historical Jesus of the Gospels (Eerdmans, 2009) and Christobiography (Eerdmans, 2019).

Médine shares on the suffering of women in Congo

My wife Médine shares her own direct experience as a Congolese woman and her observations about the experiences of other Congolese women.

COVID 19 and biblical grounds for social distancing

Nearly all of my posts are scheduled far in advance. None of them (including the recent post on the biblical book of Job) was precipitated by news of the coronavirus. But since the topic is on people’s minds, I offer here just a small possible contribution.

For those wondering whether quarantine or social distancing can be biblical: I have long taken biblical texts about isolation as potentially relevant precedent for certain conditions. (Admittedly, I have some bias: some have thought me OCD because even in regular times I wash my hands after being settings with much handshaking. But when I do, fairly rarely, catch colds, sometimes they develop into worse and protracted conditions.)

The relevant OT passages have more to do with ritual purity (and the ritual contagion of impurity) than with contagious diseases in our modern sense. Nevertheless, they also incidentally illustrate that the idea of isolation or distancing for perceived causes of a sort of contagion has some biblical warrant. (Because my PhD and my usual teaching area are NT, I should defer to my OT colleagues for correction on this, though I think all of us would agree that there is modern medical warrant for social distancing.)

Here I give the example of “leprosy” (a label used in our translations of the Bible for a range of skin conditions, but which were associated back then with ritual impurity):

“The priest shall examine the disease on the skin of his body, and if the hair in the diseased area has turned white and the disease appears to be deeper than the skin of his body, it is a leprous disease; after the priest has examined him he shall pronounce him ceremonially unclean. But if the spot is white in the skin of his body, and appears no deeper than the skin, and the hair in it has not turned white, the priest shall confine the diseased person for seven days. The priest shall examine him on the seventh day, and if he sees that the disease is checked and the disease has not spread in the skin, then the priest shall confine him seven days more. The priest shall examine him again on the seventh day, and if the disease has abated and the disease has not spread in the skin, the priest shall pronounce him clean; it is only an eruption; and he shall wash his clothes, and be clean. But if the eruption spreads in the skin after he has shown himself to the priest for his cleansing, he shall appear again before the priest. The priest shall make an examination, and if the eruption has spread in the skin, the priest shall pronounce him unclean; it is a leprous disease” (Lev 13:3-8, NRSV).

The NASB repeatedly employs the English term “isolate” in this chapter (Lev 13:4-5, 11, 21, 26, 31, 33). In Num 12:14, Miriam has to remain outside the camp for seven days after her outbreak of this condition.

In the NT, Jesus clearly transcends ritual impurity, touching the impure. He models for us compassion, trust in God’s power, and courage to cross barriers. Jesus made the impure pure. There are undoubtedly also various “spiritual” applications of the purity principles in Leviticus (such as avoiding what is spiritually impure).

Nevertheless, the application that I suggest here rests not on analogy with purity regulations per se but with recognizing the practical value of containing what was understood as contagious. We are not bound to follow levitical regulations, but we can still learn principles from them. Moreover, doing church is less about being spectators than about relationships, so we do not always need to meet 5000 strong to be the church (cf. http://www.craigkeener.org/the-new-building-program/; http://www.craigkeener.org/megachurch/).

It is not OCD to follow guidelines from the CDC (Centers for Disease Control). If the CDC (in the U.S., or equivalent professional bodies in other nations) provides warnings how to prevent the spread of something that harms our neighbor, we should do our best to comply.

Paul and the Jerusalem Church: when nationalism blinds us to God’s mission—Acts 21:17-26

Some writers today condemn the Jerusalem church for being too “Jewish.” I believe that this perspective misses the point. They were part of their culture, and they had as much right to practice Jewish customs as Paul’s gentile Galatian converts had the right to maintain gentile practices that did not contravene their new faith in the Jewish Messiah. There was nothing wrong with Jerusalem’s believers identifying with their culture; indeed, some of their culture was directly inherited from Scripture!

The problem arose only when that identification blinded many of them to God’s mission elsewhere. Commitments to nation, culture, ethnicity, denomination and the like may be honorable. But if Christ is truly Lord, then unity with the rest of our family in Christ must come first.

When Paul visited Jerusalem for the last time, Judea was in the midst of a nationalistic resurgence. Paul was aware of the dangers from Judean nonbelievers and remained uncertain how even his fellow Jesus-followers there would respond to his gift (Rom 15:31). But live or die, he was so committed to the unity of Christ’s body that he was determined to bring an offering from the gentile churches to help the poor believers in Jerusalem (Acts 21:13; 24:17; Rom 15:25-27).

A comparison with nationalism today may help us be more sensitive to the setting of Judean believers. Analogies are always imperfect, but the comparison serves as an illustration to make their setting more concrete for us. Many events of the 1960s and 1970s began shifting the United States in a direction that appeared inevitably more liberal or progressive (depending on your viewpoint). Nearly all of us now recognize some events as positive, such as the civil rights movement, greater recognition of the unfairness of male infidelity and abuse, and we as Christians also would appreciate heightened sensitivity to needs of genuine refugees. By contrast, the so-called sexual revolution has had largely negative cultural impact, weakening families and correspondingly wreaking unexpected economic costs on society. Obviously the drug culture’s impact has been largely negative, and we as Christians would also complain about the devaluing of life. So my comparison at this point is not passing wholesale judgment on what a culture deems “conservative” or “liberal” but to highlight a point of comparison with first-century Judea.

The “Reagan revolution” of the 1980s shattered the illusion that “liberal”/“progressive” trends were inevitable, again redefining the middle in public discourse. Seeds sown in that era blossomed again under George W. Bush and climaxed so far in the administration of Donald Trump. President Obama’s second term shifted many policies and much rhetoric to the left, inviting from some quarters a reaction to the right; President Trump shifted policies and rhetoric to the right, inviting strong reaction from other quarters. Increasing polarization between the two dominant political parties in the U.S., with primaries often playing to the louder voices on either side of the respective parties, have often led to massive shifts in policy with new administrations. The two-party system often makes policies a package deal.

Popular opinion in Judea experienced some similar pendulum swings. Herod the Great’s internationally powerful kingdom in Judea gave way to a series of Roman governors, until the short rule of Herod Agrippa I (AD 41-44). Agrippa had courted favor among elites in Rome, and as king he courted favor with traditional Judeans. He was wildly popular among Judeans, and his short-lived reign rekindled Judean nationalism, shattering the apparent inevitability of direct Roman rule. After Agrippa’s death (narrated in Acts 12:23), successive Roman governors exploited and misadministered the province, provoking increasing resistance. By the late 50s and early 60s—by the time of Paul’s final visit and his consequent voyage to Rome in Roman custody—tensions were nearing a breaking point. While the Judean elite (or at least its elders) tried to maintain a voice of “moderation,” mediating between the interests of Rome and their people, voices of resistance were only a few years short of open revolt.

Yet Judean believers in Jesus, though suppressed under Agrippa I (see Acts 12), now flourished. Although scholars disagree how much hyperbole may be intended, Luke reports “tens of thousands” (myriadoi) of believers in Judea (21:20). Debates about Jesus’s identity polarized Judeans far less at this point than responses to Roman abuse of power, and Judean believers shared the political concerns of their peers. At this point in Judea’s history, the most prominent gentiles with whom they had to contend had given gentiles quite a bad name, and most Judeans, unlike Jews elsewhere in the Roman world, had little on-the-ground contact with other gentiles. That believers number so many in Acts 21 shows how well they were reaching their culture in relevant ways; they were effective in contextualizing the gospel for their local setting. Most, however, had little exposure to what God was doing in other parts of the world.

These believers were “zealous for the law” (21:20), which Acts probably understands in a mostly honorable way (cf. 23:3; 24:14; 25:8; 28:23; Luke 2:24-27, 39). Paul himself is ready to show his solidarity with his people in this way (Acts 21:23-26). Paul was not against Jewish people honoring the law; he was against imposing it on gentiles as a condition for being right with God or being “first-class” believers (13:38-39; 15:1-2). Leaders in the Jerusalem church understood and agreed (21:25).

Acts is explicit, however, that these leaders understood some nuances that were lost on many of their followers. In antiquity as today, nuance can get lost in sound bites, and popular sentiment sometimes divides in binary ways. Many Judean believers assumed that if Paul was against imposing the law on gentiles, he was against the law (21:21). As James and the elders warn: “You see, brother, how many thousands of Jews have believed, and all of them are zealous for the law. They have been informed that you teach all the Jews who live among the Gentiles to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs” (21:20-21, NIV). Paul agrees with these leaders on a plan to challenge this mistaken stereotype; he bends over backwards to identify with their local interests (21:22-26). His concern, affirmed by the movement’s Jerusalem leaders, is simply that the mission beyond Judea also retains its cultural freedom (21:25). The church’s unity is paramount. Different political perspectives or cultural customs do not entitle us to assume the worst in the other’s motives. Paul was ready to do whatever necessary to try to help hold together the churches of different cultures.

Acts does not tell us how Judean believers as a whole responded, since Paul’s gesture of goodwill and solidarity is met with misunderstanding from non-believing enemies. A riot flares in the temple, and Paul ends up with one final opportunity to preach to his people in Jerusalem. He addresses them in what was now the Judean mother tongue, emphasizing again his solidarity with their zeal for the law and even his past, violent defense of his people’s customs (22:2-5, 12, 14). He goes on to preach Jesus, and no one interrupts him; perhaps partly because of the Jerusalem church’s sensitive witness, belief in Jesus is not a current political dividing point (unlike in 12:1-3).

But Paul is not willing to stop with preaching Jesus. Genuinely responding to Jesus’s Lordship means more than acknowledging him as an option or even the best option. Genuinely submitting to his Lordship brings us into solidarity with his other followers, the rest of Christ’s body. If nationalism trumps spiritual unity, then Christ is not our Lord. Those who truly follow Christ should maintain our witness to their culture, but not at the expense of our unity with brothers and sisters in Christ. Attending an evangelical church on Sunday morning does not, for example, make you a true Christian if you are burning crosses on black people’s lawns at night (or engaging in corrupt business practices, or sleeping with your neighbor’s wife, etc.)

So Paul does not simply invite the crowd to follow Jesus abstractly. Jesus had already warned that gentiles would destroy Jerusalem (Luke 19:43-44; 21:20-24). Jerusalem is already on that course of conflict, and only the true gospel of Christ, which offers love of enemies and reconciliation across cultures, can challenge that course.

So Paul climaxes his testimony in Acts 22:21: “Jesus said to me, “Go! For I’ll send you far away to gentiles!” For Paul, the good news of Christ includes and requires unity with one’s fellow believers of other cultures, a spiritual temple that matters more than the earthly one (Eph 2:18-22; cf. 2:14-15).

For the crowd, however, admitting God’s concern for gentiles was a step too far. Their experience with gentiles was a negative one. “Up to this word they listened to him. Then they raised their voices and said, “Away with such a fellow from the earth! For he should not be allowed to live” (Acts 22:22, ESV). The wise reader of Luke’s work may remember a shout from a previous generation’s Jerusalem crowd: “Away with this fellow! Release Barabbas for us!” (Luke 23:18, NRSV). Jerusalem had just rejected its final opportunity to turn back from the path of judgment—as Jesus had essentially warned (cf. Luke 19:42-44; Acts 22:18).

Paul ends up in Roman custody, a custody later described as being “the prisoner of Christ for the sake of you gentiles” (Eph 3:1). Christians often have our differing political perspectives. Insofar as possible, we must support what we believe is truth and justice. We are not, however, free to disrespect one another or break the body of Christ over our politics, culture, or secondary theological issues. To do so is to deny Christ’s ultimate Lordship. Today there are believers in most cultures in the world, and in the U.S. and many other nations we have Christians from diverse cultural backgrounds. Listening to one another’s issues can help provide nuance beyond the stereotypes.

Years ago, when my African-American pastor was sharing with a mostly white group about ethnic reconciliation, I felt my heart breaking. I felt as if Jesus was saying, “Can’t you see how it hurts me when my body is torn asunder?” I felt the pain of a body being torn apart. If we love Jesus, we must love one another—to do otherwise is to hurt not only one another, but to hurt our Lord himself.

For me, the implications this message has for the church in the U.S. seem obvious. Not least, while “America first” might sometimes or often be good for America, Jesus’s own people in the U.S. must have wider concerns, whether (for example) our brothers and sisters in northern Nigeria facing genocide from Boko Haram, our brothers and sisters in Honduras facing gang violence, or our brothers and sisters in some Asian countries facing potential disfranchisement.

But whether you live in the U.S. or (with many of my readers) in other nations, consider what implications you believe this message might have. What does it mean to love fellow believers more than the interests of our own nation, culture, party, denomination, or the like?

(A few more comments on polarization in another post)

Médine’s experience as a war refugee (audio interview)

My wife shares some of our story, especially her 18-month experience as a war refugee in Congo, in the January 3 podcast (44 minutes) at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/cbets-podcast/id1465002258