My wife Médine shares her own direct experience as a Congolese woman and her observations about the experiences of other Congolese women.

Category Archives: Africa

Academic review supporting article on plausibility of spirits

Today’s post will be of interest mainly to academics who allow for the possibility of spirits. I try to address it from a somewhat neutral academic standpoint, though neither those who know my biblical convictions nor my African experience will be surprised at my conclusions.

The First Gentile Christian was from Africa—Acts 8:26-40

When we think of Christianity in Africa today, we often think of movements that began with the witness of Western missionaries. While this may be true for some parts of Africa, it is certainly not true about all of Africa. For example, Axum in East Africa was already a Christian kingdom from the fourth century. Nubia also was predominantly Christian for roughly a millennium until its conquest and subjugation from the north.

But Christianity in Africa starts even before Christianity in Europe. Showing this requires three points. First, the official was from Africa. Occasionally someone who is exceedingly misinformed will point to sources that refer to a different “Ethiopia”; but while some ancient sources speak of Ethiopians toward the east, the land of the dawn, the land whose queen was titled the Candace was always an African kingdom south of Egypt.

The First Gentile Christian

The other two points invite more detailed comment: was this man a Gentile, and was he a genuine historical figure?

There remains some dispute as to whether this official was a Gentile. This controversy is understandable. The African court official in Acts 8:26-40 was clearly devoted to Israel’s God. Indeed, he had to be to make pilgrimage to Jerusalem; the roundtrip journey from his kingdom would have taken months, and such an extensive leave of absence would have required his queen’s permission.

Nevertheless, while he is more committed to Israel’s God than is Cornelius in the next Gentile conversion narrative (Acts 10:1—11:18), he is not a full proselyte. Luke has already narrated a proselyte even in leadership in Jerusalem’s community of believers (Acts 6:5), so he has little reason to devote such a long section to another one.

Further, while Luke includes the man’s official title once, he underlines his status as a eunuch by repeating that title five times. Male servants of queens were often eunuchs. Although the OT sometimes may use an equivalent label simply for some officials, the Greek term here is clear and Luke’s hearers would assume that the man was a genuine eunuch—a castrated man. The Greek translation of the OT often uses it for clear eunuchs, especially when the person is foreign, and/or working in relation to royal women (as here), and especially in texts closest to Luke’s period (e.g., Sirach; Wisdom of Solomon). Royal eunuchs held high status as servants of the royal house, but ancient Mediterranean society often ridiculed them as merely “half-men” for their involuntary eunuch condition.

Most relevant here was the man’s status vis-à-vis Judaism. A eunuch could not become a proselyte, that is, a full member of Israel (Deut 23:1). That refers only to official status, of course, not to God’s perspective. In the OT, an African “eunuch” becomes one of Jeremiah’s few allies and saves his life (Jer 38:7-13). More importantly, God promised to welcome foreigners and eunuchs (Isa 56:3-5), of which this man becomes the first example. This official is Jewish in faith, but because he cannot officially convert to Judaism, he remains a non-Jew ethnically.

Minimizing this African convert?

Some complain that Luke actually plays down this official’s conversion by contrast with Cornelius, whose conversion story Luke repeats, in part or in full, some three times in Acts. But Cornelius is a step further in the direction of gentiles, and points toward the narrative’s climax in Rome (Acts 28:14-31). Luke’s audience, based in the Roman empire, will naturally have special interest in the good news about Christ reaching Rome. The Cornelius narrative is also important because it signals a shift in the thinking of the Jerusalem church, and was the gentile-conversion account widely known to them. But Luke, who spends time with Philip (21:8), apparently has a less detailed account from Philip himself of a gentile’s conversion before that of Cornelius.

“Ethiopia” was the Greek title for all of Africa south of Egypt, and Greek sources often describe it as the southern “ends of the earth.” The ends of the earth is where the gospel must go (Acts 1:8), so this narrative foreshadows a larger future for the gospel in Africa. The gospel, originating in what the Roman world considered Asia, goes not only west but south. Although this official is a single person, his conversion receives nearly as much space as the preceding Samaritan revival that converted an entire community: it is a major kingdom breakthrough.

A Real Gentile Christian?

The other consideration in establishing that this official is the first gentile Christian is the question that some have raised about whether it is a true story. Most scholars recognize that Luke is writing history, and most scholars who have actually read ancient historiography recognize that historians recounted stories that came to them, rather than inventing stories from whole cloth. Luke clearly believed this story, which presumably goes back to Philip himself.

But a few scholars have argued that this account sounds more like a novel than a true story. They sometimes argue this because they say that novels liked to celebrate what was foreign and “exotic,” and they so designate this narrative. But comparing Luke’s account with actual ancient novels should quickly dispel the idea that Luke writes novelistically here. The location is not in some distant or mythical land, like in some novels’ “exotic” descriptions, but in the Roman province of Syria, on a real road leading toward old Gaza.

Moreover, unlike mythical “Ethiopians” such as Memnon or Andromeda, the Kandake (in most English translations, Candace) figures in actual historical works. In view of her title, the kingdom in view is the actual ancient Nubian kingdom of Meroë, which was rediscovered in 1722 and identified archaeologically in the early twentieth century.

Nonfiction writers on Meroe sometimes speculated about the location. Some speculations, such as cotton trees, were undoubtedly misplaced (since cotton doesn’t grow on trees). Some assumed that the area was mostly desert, or that, like India, it had rains and crocodiles. A first-century expedition in Nero’s time, however, found more foliage around Meroe, and even elephant and rhinoceros tracks.

Naturally novelists (such as Heliodorus, in his later Ethiopica) had a free hand, inventing what suited them along with a small amount of known information.Others simply made up travel stories, which sometimes fooled even some factual writers who assumed their stories were true.

Thus some supposed that Ethiopians mined metal by pulling it up with magnets. The region hosted a lion’s body with a human face (useful for eating people) and horned, winged horses. Pliny the Elder, who thought he was reporting fact, reported flat-faced, noseless people and people whose king was a dog. While writers knew of forests and crocodiles elsewhere in Africa, they also wrote of people with mouths and eyes on their chests and leather-footed crawling people. Supposedly Ethiopians originated astrology and had to flee from India after murdering King Ganges (the river’s son. They could make trees salute.

Writers told unverifiable stories about other distant lands as well. Thus the Hyperboreans in the distant, frigid north lived so long that finally they tired of living and dove into the sea. Some reported that India hosted water monsters and griffins, and ants as large as foxes that mined gold. Happily the ants retreated underground during midday heat, inadvertently enabling the Indians to steal their gold. Others told stories about Amazons, though they do not appear in non-Greek sources and in recent centuries no one had found them.

Luke’s Plausible Narrative

By contrast, Luke’s details are all plausible, and none of them clearly contradict what we know historically. That means that Luke not only does better than novelists; he does better than many historians whose sources were distorted. Luke may not have many details available from Philip, but the details that he has make sense.

Greeks used the title Kandake for many queen-mothers, some of whom ruled Meroë by themselves. One of those in the first century, for example, possibly around this time, was Queen Nawidemak. (Queen Amanitore was also somewhere around this time.)

Presumably the African official was a person of means to be able to make such a long journey (probably multiple months), traveling by boat down the Nile and then presumably by carriage to Jerusalem. The queen presumably worshiped state deities of Meroe (such as Amun), but the polytheistic nation must have had tolerance for other faiths; a Roman temple also existed on the site.

Meroë’s famous wealth is attested archaeologically and is not surprising. Meroë was ideally positioned for trade between societies to the north and those to their south. Northerners procured much ebony and ivory through them; meanwhile, a bust of Caesar has been found as far south as Tanzania. As a court official of the Candace in charge of her treasure, this traveler undoubtedly had access to considerable means. Only the wealthiest had riding carriages as here in 8:28.

Meroe had its own language, but an educated government official dealing with finance probably was fluent in Greek, since this was the main trade language with the north. Despite continuing use of Egyptian, Greek was the main language of Alexandria, as well as Egypt’s government and trade in this period; Greek was used even in capitals of Egyptian agricultural districts. Luke would quote Isaiah in Greek in any case (since he writes in Greek), but probably the official’s Isaiah scroll in this narrative was in Greek. He could have acquired the scroll in Jerusalem or in Alexandria en route to Jerusalem; the common Greek versions of the Old Testament (notably the family of texts we call the Septuagint) were translated in Alexandria and copies were probably more plentiful there. Even in Jerusalem, many tomb inscriptions (especially of the elite) are in Greek. There is little reason to doubt that the Hellenist Philip, whose primary language was Greek, would have trouble communicating with this official.

Asia of course plays a key role in the Bible: by Greek definitions, the holy land was part of Asia, and right on the boundary of Africa. The first followers of Jesus therefore were from Western Asia, from the Middle East, more specifically from Galilee and Judea and then Samaria. But the first non-Jewish follower of Jesus (ethnically speaking) was from Africa. But the message going to the ends of the earth means that it is for all humanity, whatever continent or culture or language. From the beginning, God cared about all peoples.

My wife’s life in Congo + how we got together (new video, audio interviews)

Seth and Nirva interviewed my wife Médine (49 minutes) on her experience as a war refugee, our story together, and how the Lord helped us:.

Here is the Youtube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gk-BilyJc0A

And here is the podcast episode link: https://www.freemind.fm/55

Médine’s experience as a war refugee (audio interview)

My wife shares some of our story, especially her 18-month experience as a war refugee in Congo, in the January 3 podcast (44 minutes) at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/cbets-podcast/id1465002258

A multicultural church—Acts 13:1-3

The church in Antioch spearheaded the mission to the rest of the world beyond Judea. Nearly all Christians today, and certainly all Gentile Christians, have spiritual roots in this church in Syria. Apart from this mission, the church could have been stillborn in the first century, had the Holy Spirit allowed such a thing to happen.

But the Antioch church’s mission began as an accident—or better yet, simply grew naturally. Once it began, however, the church became intentional about carrying out the task further.

Some of the first followers of Jesus were apparently ready to wait for God’s kingdom in Jerusalem—until Saul of Tarsus began persecuting the church there (Acts 8:3). Then the believers from there were scattered (8:4), and the Greek-speaking, immigrant Jewish believers in Jerusalem scattered to other places where they could speak Greek. Although rural Syria spoke Aramaic, the dominant language in cosmopolitan Antioch was Greek.

Eager to share their experience with others, these scattered, bicultural believers became unintentional missionaries (11:19-20). International migrations today often spread the gospel also. In some Western nations where traditional Christianity has been on the decline, for example, African, Asian and Latino/a Christians are growing new, evangelizing churches.

Unintentional missionaries—Christians scattered due to persecution but sharing Christ where they traveled—started the first house-churches in Antioch (Acts 11:19). These first Antioch Christians, living and working among Gentiles as well as Jews, began sharing the gospel with Gentiles (Acts 11:20). (The likeliest Greek reading of 11:20 speaks of “Hellenists,” a term used earlier for Greek-speaking Jews in Jerusalem in 6:1. Here, however, Hellenist Gentiles were in view—Greek-speaking Syrians.) Thus it was not surprising that they would eventually consider evangelizing Gentiles elsewhere. In fact, they embraced among them a former leader of the persecution that scattered them to begin with: Saul of Tarsus (Paul), who now had a call to evangelize the Gentiles (Acts 11:26).

Antioch was the major cosmopolitan center of the eastern Roman Empire, attracting a wide range of people from various parts of the Empire. Antioch’s various residents, already experiencing geographic and cultural transition, often tended to be more open to new ideas than those who had remained for a long time in their traditional location. Ministering to such a wide range of immigrants, the leaders of the Antioch church reflected similar diversity among themselves.

The leaders of the church were prophets and teachers (Acts 13:1). (Some think that the first three names, including Barnabas, were prophets, and the last two were teachers; but Barnabas also taught, according to 11:26. Probably all had both gifts, although they may have varied in their emphases.) Some of these leaders presumably came from Jerusalem (11:27), including Barnabas (11:22). Most, however, at least had significant cross-cultural backgrounds. For example, Barnabas, though from Jerusalem most recently, was originally from Cyprus (4:36); he probably had ties with some of the Cypriotes who helped evangelize Antioch initially (11:20).

Besides Barnabas, the leadership team included Simeon called “Niger” (13:1). Simeon was a common Jewish name, and “Niger” a common Roman name, which could suggest that he was a Jewish Roman citizen like Paul. But in this case, the expression “who was called Niger” differs from the other names in the list, perhaps suggesting a nickname. In this case, it would be meant descriptively: “Simeon the Dark” or “Simeon the Black,” observing his dark complexion, perhaps from northern Africa.

Less debatably, Lucius was explicitly from Cyrene in North Africa (13:1), and thus was perhaps one of the original founders of the Antioch church (11:20). Cyrene was in an area earlier settled by Phoenicians, with indigenous North African inhabitants and many Greek and Jewish settlers (sometimes estimated at one-third each). The culture included a mix of these various elements. “Lucius” was a common Greek name, but non-Greeks also used Greek names in places where Greek was spoken. Many non-Jews converted to Judaism, so we do not know the ethnic background of Lucius’s ancestors.

Between Lucius from North Africa and Simeon the Dark one may find significant African representation in leadership in this Greco-Asian church. (Greeks and Romans considered both Judea and larger Syria to be in Asia, so the entire leadership team likely comes from Asia and Africa. Europeans and their descendants should not feel left out, however, since in Acts Paul is eager to preach in Rome, and Romans 15 shows that he also wanted to evangelize Spain.)

Perhaps of special interest to many African-American Christians, the list may also include those descended from slaves. That Manaen was “brought up with” Herod Antipas could mean that he was a playmate from another noble family, but it could also suggest that he was a family servant. In that culture (as opposed to U.S. history) an aristocratic family’s servant could wield great social power and wealth, whether before or after being freed. Often aristocrat boys freed their servant playmates when both grew up, providing them powerful positions.

In Manaen’s case, this is merely a possibility. In Saul’s (Paul’s) case, however, it is likely. A majority of Jews who were Roman citizens were so because their ancestors had once been slaves in Rome. (In the first century BCE, Rome enslaved many Judeans and brought them to Rome.) Once a Roman citizen freed a slave under certain conditions, that slave became a Roman citizen, as did the slaves’ descendants.

Saul of Tarsus was probably one of the Cilicians who belonged to the synagogue of Freedpersons in Acts 6:9. The term translated Freedpersons there designates those freed by Romans, hence signifying this synagogue as a prestigious institution in Jerusalem—a congregation started by Jewish Roman citizens. Acts 6:9 notes that this synagogue of Freedpersons included Jewish people from various locations (including Cilicia, where Tarsus was, and where Saul’s ancestors may have migrated from Rome). It thus seems likely that Paul was a Roman citizen (16:37) because, several generations earlier, his ancestors were slaves in Rome.

In any case, this list of leaders shows a great diversity of backgrounds. What matters more than all the differences, though, is what binds them together. These leaders worship God, praying and fasting, and are ready to hear His call when He speaks (Acts 13:2). Whatever our diverse backgrounds on other points, the one God we serve unites us by his Spirit. This diverse, cosmopolitan church, with its diverse leadership team, birthed a vision that Jesus had already imparted in Acts 1:8. Empowered by the Spirit, two emissaries from this church were preparing to reach the world!

Suffering of Christians in Nigeria

Christianity Today recently provided essential information for the situation of Nigerian Christians. https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2018/november/nigeria-fulani-boko-haram-no-cheeks-left-to-turn.html

That link lets you read only the beginning of the article unless you are logged in as a subscriber, but CT gave me permission to make available another link, this one to the full article I wrote some years ago, before public news was talking about Boko Haram, etc. (based on my observations and interviews from three summers in Nigeria and continuing contact there): https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2004/november/23.60.html?share=RLlxvcfn%2fHfyByjmYm8xWxb8glmbImWN

Let’s pray for our brothers and sisters in the northern and middle belt states of Nigeria, whose suffering can be very severe.

The student named Sunday in the article, Sunday Agang, has gone on and finished a PhD and now teaches back in Nigeria, working for peace between Muslims and Christians.

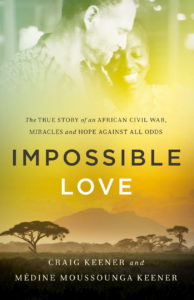

Settling in a new land—Exodus 2:16-22

When I travel to speak in various parts of the world, my hosts show me great hospitality. I miss my wife and kids, but otherwise life is pretty comfortable, apart from long flights. But that’s not always the case with people who relocate to new lands to live. My wife and children came to the United States from Africa so we could be together as a family, but when my wife was first an international student in France, she was sometimes destitute. At times when her scholarship was delayed, she subsisted on bread and water. (Part of her experience as an international student appears in a chapter of our book, Impossible Love.) Shared faith gave her a church family away from home, but life can be hard for immigrants, temporary or long-term, having to find homes in new cultures.

When Moses came to Midian, he rescued some young women from shepherds who were asserting their superior strength over them (Exod 2:16-17). But that left Moses without friends among the shepherds—and apparently without any other local friends either. Moses had nowhere to go and needed to be attached to some household, so he may have been disappointed when the young women he had helped left without inviting him home for a meal. Their failure was a breach of Middle Eastern hospitality, as their father quickly pointed out (2:20). A meal together established a covenant relationship, and Moses remained with Jethro, who gave him his daughter in marriage (2:21) perhaps something like how Jacob received not only a place to stay but eventually also a wife (or two) in Haran. Abram also broke bread with a priest of God Most High (Gen 14:18-20), and Joseph also married a priest’s daughter (her father’s office appears every time that Asenath is mentioned; Gen 41:45, 50; 46:20).

Also like Joseph (Gen 41:52), Moses gives one of his sons (Gershom) a name that signifies being a stranger in a foreign land (Exod 2:22). (One might also suggest that “Gershom” could play on how the shepherds “drove away” the daughters; cf. ygarshum in 2:17 with gershom in 2:22. But there seems no possible connection there except the sound.) Moses had grown up as a third-culture child, fully welcome in neither Hebrew nor Egyptian culture. Now he was again an outsider in Midianite culture. His previous background, however, helped prepare him for this status; those not fully attached to any culture are sometimes those best able to adapt to other cultures. His disadvantage in one setting has become his advantage in adjusting to another setting.

(For other posts on Exodus, see http://www.craigkeener.org/category/old-testament/exodus/.)

The story of the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8:26-40

Some regard the story as unreliable, but I argued in an article in 2008 that we have good reason to believe that the account is in fact reliable. I also worked some with cultural background about this passage.

The article is available for download or reading here (Andrews University Press):

Impossible Love brief sale on Kindle

I was just reminded that Impossible Love–Médine’s experience as a war refugee and how we got together–is now on sale for $2.99 at some online vendors just until May 12 (Friday) and at the MOMENT even down to $1.99 at:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B012H100VS/ref=cm_sw_r_tw_dp_x_CBJezbKPDHV1Y