Paul does his best to transcend others’ prejudices and cultural barriers to share good news in Athens.

Category Archives: Missiology

A multicultural church—Acts 13:1-3

The church in Antioch spearheaded the mission to the rest of the world beyond Judea. Nearly all Christians today, and certainly all Gentile Christians, have spiritual roots in this church in Syria. Apart from this mission, the church could have been stillborn in the first century, had the Holy Spirit allowed such a thing to happen.

But the Antioch church’s mission began as an accident—or better yet, simply grew naturally. Once it began, however, the church became intentional about carrying out the task further.

Some of the first followers of Jesus were apparently ready to wait for God’s kingdom in Jerusalem—until Saul of Tarsus began persecuting the church there (Acts 8:3). Then the believers from there were scattered (8:4), and the Greek-speaking, immigrant Jewish believers in Jerusalem scattered to other places where they could speak Greek. Although rural Syria spoke Aramaic, the dominant language in cosmopolitan Antioch was Greek.

Eager to share their experience with others, these scattered, bicultural believers became unintentional missionaries (11:19-20). International migrations today often spread the gospel also. In some Western nations where traditional Christianity has been on the decline, for example, African, Asian and Latino/a Christians are growing new, evangelizing churches.

Unintentional missionaries—Christians scattered due to persecution but sharing Christ where they traveled—started the first house-churches in Antioch (Acts 11:19). These first Antioch Christians, living and working among Gentiles as well as Jews, began sharing the gospel with Gentiles (Acts 11:20). (The likeliest Greek reading of 11:20 speaks of “Hellenists,” a term used earlier for Greek-speaking Jews in Jerusalem in 6:1. Here, however, Hellenist Gentiles were in view—Greek-speaking Syrians.) Thus it was not surprising that they would eventually consider evangelizing Gentiles elsewhere. In fact, they embraced among them a former leader of the persecution that scattered them to begin with: Saul of Tarsus (Paul), who now had a call to evangelize the Gentiles (Acts 11:26).

Antioch was the major cosmopolitan center of the eastern Roman Empire, attracting a wide range of people from various parts of the Empire. Antioch’s various residents, already experiencing geographic and cultural transition, often tended to be more open to new ideas than those who had remained for a long time in their traditional location. Ministering to such a wide range of immigrants, the leaders of the Antioch church reflected similar diversity among themselves.

The leaders of the church were prophets and teachers (Acts 13:1). (Some think that the first three names, including Barnabas, were prophets, and the last two were teachers; but Barnabas also taught, according to 11:26. Probably all had both gifts, although they may have varied in their emphases.) Some of these leaders presumably came from Jerusalem (11:27), including Barnabas (11:22). Most, however, at least had significant cross-cultural backgrounds. For example, Barnabas, though from Jerusalem most recently, was originally from Cyprus (4:36); he probably had ties with some of the Cypriotes who helped evangelize Antioch initially (11:20).

Besides Barnabas, the leadership team included Simeon called “Niger” (13:1). Simeon was a common Jewish name, and “Niger” a common Roman name, which could suggest that he was a Jewish Roman citizen like Paul. But in this case, the expression “who was called Niger” differs from the other names in the list, perhaps suggesting a nickname. In this case, it would be meant descriptively: “Simeon the Dark” or “Simeon the Black,” observing his dark complexion, perhaps from northern Africa.

Less debatably, Lucius was explicitly from Cyrene in North Africa (13:1), and thus was perhaps one of the original founders of the Antioch church (11:20). Cyrene was in an area earlier settled by Phoenicians, with indigenous North African inhabitants and many Greek and Jewish settlers (sometimes estimated at one-third each). The culture included a mix of these various elements. “Lucius” was a common Greek name, but non-Greeks also used Greek names in places where Greek was spoken. Many non-Jews converted to Judaism, so we do not know the ethnic background of Lucius’s ancestors.

Between Lucius from North Africa and Simeon the Dark one may find significant African representation in leadership in this Greco-Asian church. (Greeks and Romans considered both Judea and larger Syria to be in Asia, so the entire leadership team likely comes from Asia and Africa. Europeans and their descendants should not feel left out, however, since in Acts Paul is eager to preach in Rome, and Romans 15 shows that he also wanted to evangelize Spain.)

Perhaps of special interest to many African-American Christians, the list may also include those descended from slaves. That Manaen was “brought up with” Herod Antipas could mean that he was a playmate from another noble family, but it could also suggest that he was a family servant. In that culture (as opposed to U.S. history) an aristocratic family’s servant could wield great social power and wealth, whether before or after being freed. Often aristocrat boys freed their servant playmates when both grew up, providing them powerful positions.

In Manaen’s case, this is merely a possibility. In Saul’s (Paul’s) case, however, it is likely. A majority of Jews who were Roman citizens were so because their ancestors had once been slaves in Rome. (In the first century BCE, Rome enslaved many Judeans and brought them to Rome.) Once a Roman citizen freed a slave under certain conditions, that slave became a Roman citizen, as did the slaves’ descendants.

Saul of Tarsus was probably one of the Cilicians who belonged to the synagogue of Freedpersons in Acts 6:9. The term translated Freedpersons there designates those freed by Romans, hence signifying this synagogue as a prestigious institution in Jerusalem—a congregation started by Jewish Roman citizens. Acts 6:9 notes that this synagogue of Freedpersons included Jewish people from various locations (including Cilicia, where Tarsus was, and where Saul’s ancestors may have migrated from Rome). It thus seems likely that Paul was a Roman citizen (16:37) because, several generations earlier, his ancestors were slaves in Rome.

In any case, this list of leaders shows a great diversity of backgrounds. What matters more than all the differences, though, is what binds them together. These leaders worship God, praying and fasting, and are ready to hear His call when He speaks (Acts 13:2). Whatever our diverse backgrounds on other points, the one God we serve unites us by his Spirit. This diverse, cosmopolitan church, with its diverse leadership team, birthed a vision that Jesus had already imparted in Acts 1:8. Empowered by the Spirit, two emissaries from this church were preparing to reach the world!

Are There Apostles Today? (part 3)

Are there apostles today? As noted in the previous two posts, that depends on what you mean by an apostle. If by “apostle” you mean one of the Twelve, which is the most common use of the term in the Gospels, the answer must be No. But Paul uses the term in a broader sense than this (e.g., Rom 1:1, 13 16:7; 1 Cor 15:5-7; Gal 1:19; 1 Thess 1:1 with 2:6-7). In this broader sense, one can allow for continuing apostles. That does not settle what they are: some take them to be missionaries, others take them to be bishops, still others (including myself) take them to be those breaking new ground for the kingdom (such as missionaries or others reaching new areas in ways foundational for the gospel there).

But does that mean that everyone who calls himself or herself an apostle does so appropriately and wisely?

Not simply administrators or CEOs

I thank God for those who are gifted administratively. But biblically, apostles are not given to administratively govern the church. This view of apostolic governance fits the later Christian tradition of apostolic succession through bishops accepted in some churches. I have no quarrel with those who use such language provided (as in those churches) those who employ the title are clear what they mean by it when using it.

But most who publicly claim apostolic authority today do not belong to such churches. Rather, they want to appeal to the New Testament model of apostleship. Yet the NT model is a model not of institutional authority, which could belong to local elders, so much as gifted servant-leadership. Paul was an apostle and a leader to the churches he started, yet he usually reasoned with them and gave direct commands only when necessary. Paul warned against those who wanted to be compared to his apostolic ministry who were not doing what he was doing—starting new churches in their own spheres.

Simply convincing other people’s converts of one’s different doctrine does not make one an apostle. That is not to deny the authority of those God has called to teach his word (I would in fact be one of the last people to suggest that), but to point out that by itself this is not what apostleship is. In birthing a new movement, John Wesley did help many people who were already Christians to see the truth more clearly, but he and his movement were also strategic in reaching nonbelievers.

I see Wesley’s ministry as an example of apostolic ministry, without thereby affirming everything that he did or taught. I suspect the same for William and Catherine Booth, cofounders of the Salvation Army. Today an example of apostolic ministry with which some are familiar could be Rolland and Heidi Baker, who have catalyzed a church planting movement in Mozambique. And I meet many from the Majority World who could fit such a description.

Perhaps in a culture where the gospel was more widespread, as it was in Jerusalem c. A.D. 50, apostles spent a lot of time leading believers, alongside the local elders of the Jerusalem church (cf. Acts 11:30; 15:2, 4, 6, 22-23; 16:4). But they broke ground for that church initially, and at least some kept doing so in other areas while retaining Jerusalem as a home base (9:32-43). Within a few years after this, most of the Twelve had apparently left Jerusalem (cf. Acts 21:18). Eckhard Schnabel is probably right in suggesting that they devoted themselves to mission outside Jerusalem (see his Early Christian Mission [2 vols.; Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity; Leicester, U.K.: Apollos, 2004). In this respect, the apostolic model they followed is the same as exemplified by Paul.

Those who come along and tell people to follow them because they are apostles are not birthing churches or movements; they are raiding other ministers’ sheep pens. If they have truth for God’s people, they should trust the gift God has given them to function effectively and equip God’s people; this is not the same as claiming authority over churches by appealing to an office they have not demonstrated.

Conclusion

Are there apostles today? I believe that God continues to use apostles, like other ministers of God’s message, to bring Christ’s body to maturity and to equip God’s people for ministry to the world (Eph 4:11-13). I expect that they will continue until the time of the end (Rev 18:20). Those who disagree with using the title for anyone today still generally recognize that God uses some people to evangelize new regions and break new ground, so the disagreement in this sense is a semantic one. Again, neither cessationists nor continuationists such as myself claim that anyone is writing Scripture today, and all of us do believe in “missionaries.”

But in any case, the title cannot apply simply to anyone who wants to claim it. Those who have not demonstrated the humility and sacrifical service of apostles should not claim the title. People should not leave their churches just to follow someone who claims the title. Recall again the initial praise that Jesus offered the church in Ephesus: “I know your works … I know that you cannot put up with evildoers, and you have tested those who call themselves ‘apostles’ but are not, and have found them to be false” (Rev 2:2).

Are There Apostles Today? (part 2)

Are there apostles today?

As noted in part 1, that depends on what you mean by an apostle. In contrast how some define it today, biblical apostleship does not seem to be a matter of summoning people to accept one’s authority. The Jerusalem church had elders in addition to the founding apostles; the elders may have exercised administrative authority, whereas the apostles’ authority inhered in their mission. Paul had a special apostolic authority in relation to the Corinthian Christians because he had birthed and labored over them (1 Cor 9:2); when he was coming to a church he had not founded, however, he simply offered to share with them from his spiritual gift (Rom 1:11-12). Even the apostle Peter is clear that church leaders as a whole should not “lord it over” others (1 Pet 5:3).

Although some passages about apostleship in the NT do mention signs (e.g., 2 Cor 12:12; Matt 10:8), they emphasize sufferings even more heavily (e.g., 1 Cor 4:9-13; Matt 10:16-39). Apostleship was not an authority to boast in, but a calling of service that involved suffering. An apostle as an agent of Christ was to act in Jesus’s name, as in a sense all of us Christians are to do; that means that Jesus should get all the credit for the works (cf. Rom 15:18-19; Acts 3:12-16; 14:15). Where the agent rather than Jesus takes credit, eventually the agent may be left to work on their own, instead of the Lord doing the work through them. That is, they may have to depend on marketing gimmicks instead of God’s blessing to maintain their hearing. One wonders if this has not sometimes happened.

In Scripture, apostles apparently normally break new ground, rather than simply laying on another’s foundation (Rom 15:20). The Jerusalem apostles initially broke ground for ministry in Jerusalem and then oversaw the work for some time; Paul and his coworkers broke ground in the cities of the northern Mediterranean world. (Some of his coworkers occasionally appear to be apostles as well, as in Rom 16:7; 1 Thess 2:6-7; at least some, such as Timothy, were converted after him, Acts 14:6-8; 16:1-3.) Paul had suffered and done the work, but his rivals wanted to take over his work and boast in it. They were poaching in the sphere of ministry God had given him, and Paul charges them with false apostleship (2 Cor 10:12-16; 11:12-13).

If some today believe that God has called them to be apostles according to the biblical model, they may need to distinguish their ministry from practices that distort biblical apostleship. Otherwise all those who use the term may face a backlash just as happened in antiquity. In Revelation and the Didache, those who claimed to be apostles or prophets were tested. Soon after that, the church began limiting the title to the Twelve (the narrower Lukan usage rather than Paul’s broader usage). Without being harsh toward those who abuse the label “apostles,” those who use the title but stand for a different kind of ministry should clarify that their mission is different. They are called to serve the church, not to divide it.

I discuss this matter further in part 3 (to be continued).

Are There Apostles Today? (part 1)

Are there apostles today? That sort of depends on what you mean by an apostle. If by “apostle” you mean one of the Twelve, which is the most common use of the term in the Gospels, the answer must be No. If by “apostle” you mean someone who writes Scripture, although most biblical apostles didn’t write Scripture and not all New Testament authors were apostles, the answer must be No. By definition, the “canon,” or measuring stick, for revelation is the agreed-upon works either endorsed by Jesus—the Hebrew Bible—or written by witnesses of Jesus or their immediate circle. One need not claim that any spiritual gifts have ceased to claim that the first century has ceased!

Apostles besides the Twelve

But if by “apostle” you mean other commissioned agents of the Lord besides the Twelve, no text suggests that these must cease, so I am inclined to think that this ministry continues, and remains one of the ministries necessary to bring Christ’s body to maturity (Eph 4:11-13). (Sometimes people aver that an apostle must have seen Christ, based on 1 Cor 9:1, but Paul there asks three rhetorical questions, and apostleship is equated with seeing Christ no more than it is equated with being free. 1 Cor 15 also does not equate apostleship with seeing Christ.)

Whether you agree with me on that point or not, Paul does speak of many apostles besides the Twelve, including himself (Rom 1:1, 13), clearly a group of early apostles beyond the Twelve (1 Cor 15:5-7, maybe related to the followers sent in Luke 10:1), James the brother of Jesus (Gal 1:19), Silas and Timothy (1 Thess 1:1 with 2:6-7), Andronicus and Junia (Rom 16:7).

Although the foundation stones of the New Jerusalem include the twelve names of the twelve apostles of the lamb (Rev 21:14), Revelation endorsed still testing those who claimed to be apostles (Rev 2:2). The Didache, a Christian document from the late first or possibly early second century, also advises testing apostles (Did. ch. 11). Later apostolic fathers often settled into using the title just for the Twelve plus Paul (a combination usage nowhere followed in the New Testament itself), but the New Testament usage is wider.

What “apostle” in the broader sense means is a legitimate debate, since the New Testament never provides a definition. Putting together the Twelve and the wider use in Paul, I suspect that “apostles” are people who lay foundations in new areas (Rom 15:20). Today we might think of those laying new ground in previously unevangelized regions or spheres. They also mentor other leaders there to multiply the work.

Many such pioneers do not claim the title for themselves; yet some who are not pioneering anything do aspire to the title. What does it mean in the latter case to “test” apostles (Rev 21:14)? That (rather than a debate about the continuation of apostles) is what this post primarily addresses.

Today there are reports of people claiming to be apostles and calling others to accept their authority, sometimes summoning them to abandon denominational or other ties. What should we make of this reported behavior?

Various uses of the title in various churches

Before I suggest some criticisms of that agenda, let me first qualify what I am not saying. First, a criticism of the movement does not depend on the theological and biblical question of whether apostles exist past the first century. Christians hold various views on this point. Certainly the idea of continuing mission as “apostolic” in a general sense is not new; thus for example Bartholomew I Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople addressed the Synod of Bishops of the Catholic Church on Oct. 18, 2008: “Missions and evangelization remain a permanent duty of the Church at all times and places; indeed, they form part of the Church’s nature, since she is called ‘Apostolic’ both in the sense of her faithfulness to the original teaching of the Apostles and in that of proclaiming the Word of God in every cultural context every time” (http://www.focolare.org/repository/PDF/081018_InterventoBartolomeoI_en.pdf, accessed Nov. 28, 2015; I owe this reference to Scott Sunquist, The Unexpected Christian Century, Baker Academic, 2015, p. 181).

Likewise, Francis Asbury, the inaugural leader of U.S. Methodism, labored for “an apostolic order of poverty and itinerancy” (Cracknell and White, Methodism, 48) and “an apostolic form of Church government” (his valedictory address of 1813, reproduced in Christian History 114 [2015]: 39).

Although virtually everyone agrees that the Twelve and (an entirely separate question) the writing of Scripture are complete, some argue that there is a sort of apostolic succession among bishops. Others use the broader Pauline sense of apostleship and believe that this gift continues (as missionaries, church planters, or perhaps specially influential founders of movements such as John Wesley). Personally, I do not find compelling any biblical arguments that apostleship in this broader sense had to cease (nor that it requires a resurrection appearance, which I believe misreads the relevant texts). I will not argue that point here, however, because the issue here is a different one.

All of that is beside the present point: Christians have disagreed among ourselves over issues of church order for centuries, and most of us would acknowledge that we have structures in our denominations or movements that are not mentioned in Scripture. The issue is whether those who are behaving in the way mentioned above fit the biblical understanding of apostolic ministry, and that, I believe, is a legitimate question. Recall the commendation of the church in Ephesus in Revelation 2:2: “You tested those who call themselves apostles, yet are not, and you found them to be false.” The early Christian document called the Didache urges Christians to welcome those who call themselves apostles as agents of the Lord (Did. 11.4). If, however, the apostle seeks support rather than opportunity for ministry, the Didache cautions, he is a false prophet (Did. 11.6). Of course, in those days one did not need to pay for air time.

The second qualification is that some simply employ the term as a leadership title, the way other churches have “bishops” and the like. Again, Christians already disagree among ourselves regarding church order, and usually this does not keep us from getting along. If people are seeking not titles and positions but are seeking to influence people positively, they are doing what any good writer or minister seeks to do. Whatever we call them, we simply need to evaluate whether their influence is positive.

Moreover, if apostleship in the sense of influential leaders does continue beyond the first century, some influential leaders today might fill that role whether or not the rest of us think that use of the title is discreet. One of the first people who comes to my mind is a noncharismatic (though not anticharismatic) friend who has exercised huge influence for Christ in Nigeria, where he has spent decades in ministry. Whatever one thinks of “apostles” today, his ministry seems closer to that New Testament ministry category than to any other that I can think of. I am not sure that he would own the title for himself. I knew a church planter in Congo named Eugene Thomas who had a similar ministry; he didn’t believe that apostles or tongues were for today, but apart from apostolic “signs” (2 Cor 12:12), he fulfilled most of the other “criteria” for the broader definition.

What should real apostles look like? That will be the subject of part 2 (to be continued).

Moses as a third-culture kid—Exodus 2:7-10

Did Moses know that he was a Hebrew? Contrary to some of the movies we see (including my beloved Prince of Egypt!), he presumably did. In many periods in Egypt’s history, Asians could serve in the Egyptian court. Disloyalty to Egypt, however, would be harshly punished. A Hebrew less than fully assimilated in Egyptian culture and too Egyptian to be trusted by many of his fellow Hebrews, Moses was like what we call today a “third culture kid” (like many children of immigrants, refugees, missionaries, diplomats or other cross-cultural settings, and sometimes like children in bicultural homes). (Midianites who met him viewed him as Egyptian, Exod 2:19.)

In some cultures a child can identify with multiple cultures, but Moses grew up in a setting of prejudice where his Hebrew identity would have counted as a liability. So Moses grew up as a Hebrew, but also in Egyptian culture. This experience continued until he grew up (Exod 2:11).

Miriam interceded for Moses when she saw the compassion of Pharaoh’s daughter, offering to secure a Hebrew wetnurse for the child (Exod 2:7). The period of nursing might take two years, and the nurse needed to be one who could provide milk for the child—in this case, Moses’s own mother, who now got paid to nurse her own baby (2:8-9).

Although Moses’s mother was able to nurse him, once he was weaned she had to return him to Pharaoh’s daughter, who adopted Moses as her own son. The new mother also named him “Moses,” commemorating her finding him and drawing him from the water (2:10). “Moses” is not an unusual component of an Egyptian name, but Pharaoh’s daughter may have used a wordplay on the Hebrew words for drawing him out of the water because the child was a Hebrew. (Although the Hebrews lived in close proximity, in Goshen, in state servitude but living in their own mud-brick homes, she may have had to consult with Hebrew servants or others to find the right wordplay.) The providential irony here is that under Moses’s leadership God would someday deliver all his people through water.

Moses thus grew up in privilege, yet was also aware that he was Hebrew. Moses belonged to two cultures, but an event would soon force him to choose one at the expense of the other—in the short term costing him both (Exod 2:11-15).

(For other posts on Exodus, see http://www.craigkeener.org/category/old-testament/exodus/.)

Acts introduction 6: evangelism, introduction to Acts

This is the sixth free 1-hour video on the Acts of the Apostles.

Heritage and mission, Word and Spirit

Luke’s Gospel begins and ends in Jerusalem. His sequel, the Book of Acts, begins in Jerusalem but ends in Rome. Theologically, this is movement from heritage to mission: holding on to the heritage but moving forward into mission. In the same way, we need to be grounded in the Scriptures, so our action will be consistent with all that God has done before us, yet also moved by the Spirit, so we can reach those parts of humanity not yet reached.

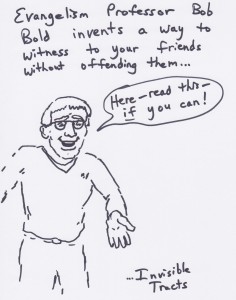

Sharing your faith inoffensively (cartoon)

Ancient apologetics

3 minutes: ancient apologetics. How Paul was able to use Jewish apologetic arguments when engaging with ancient intellectuals. Also apologetics vs. skepticism today. 3-minute video clip by Acts scholar Craig Keener. For 23 free lectures on Acts, see http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/DigitalCourses/00_DigitalBiblicalStudiesCourses.html#Acts_Keener