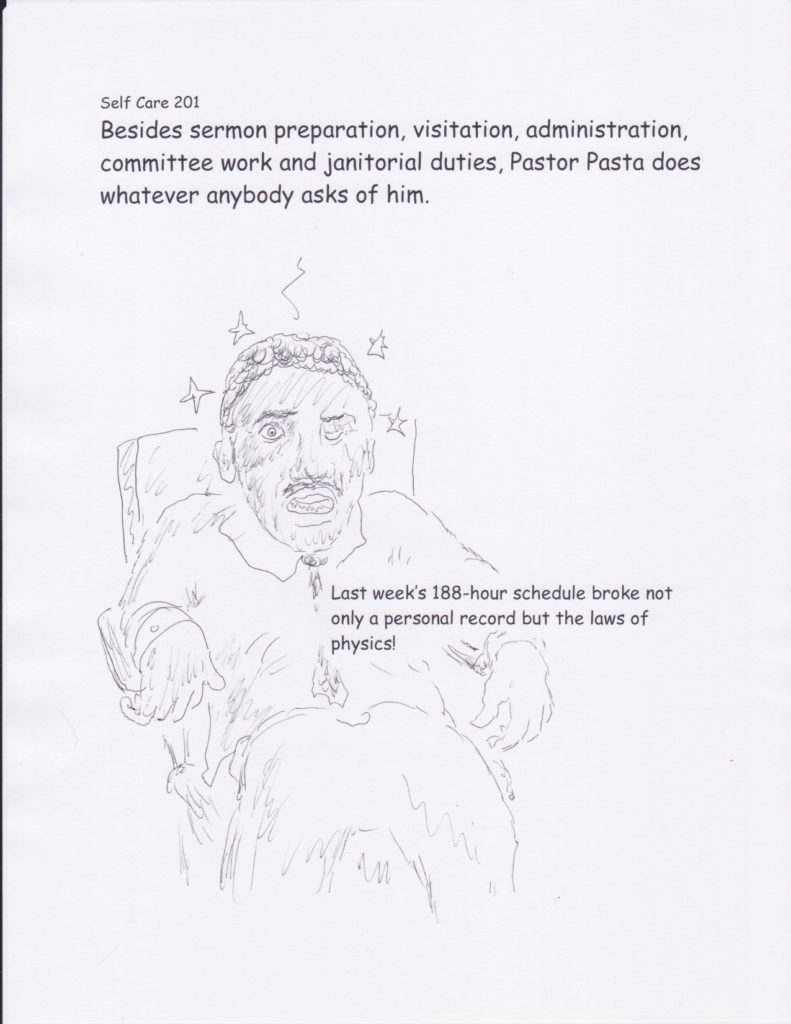

Self-care for busy pastors

Some biblical theology of leadership, provided by Jesus. One of the two models is that of Jesus’s own ministry:

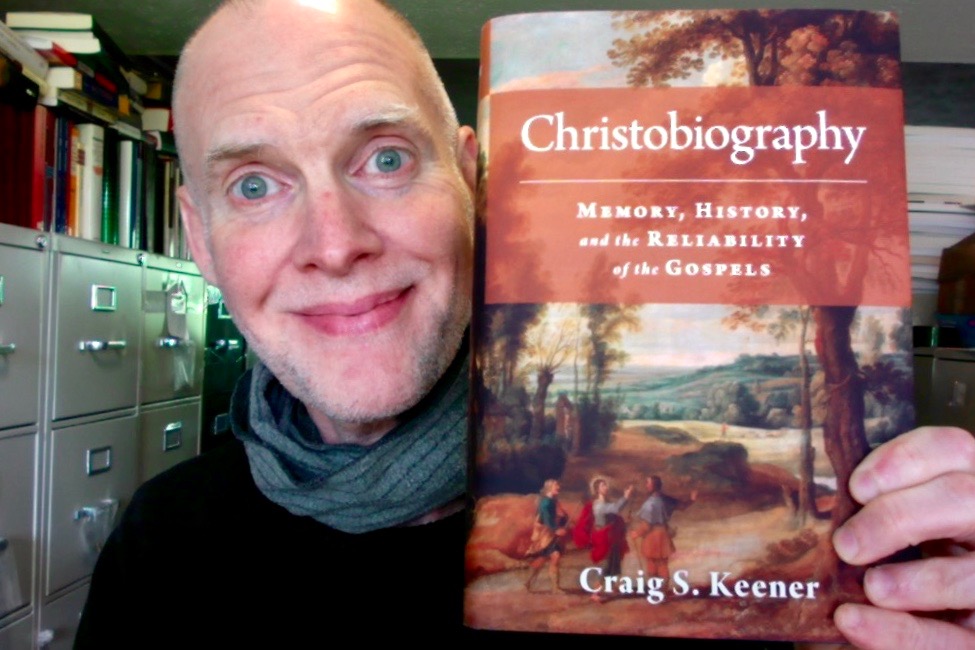

Mike Licona interviews Craig about differences in the Gospels.

Luke wrote two volumes, the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts. His second book, the Book of Acts emphasizes the mission to the nations—a crucial mission without which we would not have Gentile Christians today (though we might at least have Messianic Judaism). But before recounting the mission to Gentiles in Acts, Luke prepares his audience by recounting Jesus’s mission to other kinds of outsiders in his first volume, the Gospel of Luke.

If we want to be ready for mission in another location, we can start preparing by crossing cultural and other barriers closer to home.

Throughout Luke’s Gospel, Jesus ministers to those lacking status and power in his culture (such as the poor and non-elite women). Among those alienated from society, he reaches out to “sinners”—those marginalized by virtue of their behavior. His kingdom does not depend on human political or military power; he pursues the lowly, showing that God is not impressed with our worldly credentials. Yet Jesus not only ministers to the marginalized; he builds his new kingdom around them.

Scripture often reports that God is near the lowly but far from the proud (e.g., Matt 23:12; Luke 1:52; 14:11; 18:14; Jms 4:6; 1 Pet 5:5); he reveals himself in human weakness more than in what the world deems power (1 Cor 1:18-26; 2 Cor 12:9; 13:4). Jesus welcomes everyone, but it is those who recognize their desperate need of him who most welcome him. If we recognize our need to depend fully on God, we are blessed. If we do not, we need to spend more time among the broken and the lowly, learning from their hearts.

In Luke 7:36-50, he welcomes the controversial gift that one such marginalized person offers.

It was considered pious to invite a popular sage over for dinner, and Simon the Pharisee has invited Jesus for dinner (Luke 7:36). At banquets, guests typically reclined on large, backless couches (three or four diners per couch), their feet pointed away from the tables; sometimes outsiders might come watch. A woman of ignoble repute in the community (so 7:37) enters the house and begins washing Jesus’s feet, wiping them with her hair. Simon is offended: surely a prophet like Jesus would know this woman’s ill repute. Indeed, in his culture respectable married women (i.e., respectable adult women) covered their hair in public. Thus by wiping Jesus’s feet with her hair, as far as Simon was concerned, the woman put her sinfulness on display!

But Jesus is indeed a prophet—he knows what Simon is thinking. Jesus helps Simon to realize that those who recognize their need for forgiveness most are the most grateful to receive it. Then Jesus, though still addressing Simon, turns away from the table to finally face the woman. Washing Jesus’s feet, she has been outside the circle of couches; banqueters reclined on their left elbows and their feet pointed away from the tables (after all, who wants someone’s stinky feet in their face?)

Jesus reminds Simon that he offensively failed to provide Jesus with the most basic, expected courtesies in their culture. A host should provide a guest water for washing the feet (though a respectable host would not wash the guests’ feet himself, a more servile task). Likewise, one should give a light kiss of respect to a teacher; one might also provide oil for anointing. Simon has failed in all these courtesies expected of a host. Jesus might be a special guest, but for Simon, Jesus is not that significant, compared to Simon and his peers.

By contrast, this woman has provided Jesus all the honors that Simon failed to offer—displaying gratitude for her forgiven sins. By linking forgiveness to their treatment of himself, Jesus implies that he himself is the bearer of divine forgiveness. By honoring or dishonoring him people show their response to grace.

Meanwhile, other table guests recoil in horror from Jesus’s words: how can he forgive sins (7:49)? They do not recognize how central Jesus is to God’s plan. They do not understand his identity. And, like Simon, they are proud, more ready to judge Jesus than to learn from him. All because he welcomes sinners!

When we look down on others who received grace after we did (perhaps the incarcerated, or unwed mothers, or even someone who wronged us personally), we forget that we, too, can be saved only by grace. Of course, Jesus is not offering cheap forgiveness to those choosing to remain in sin; he forgives those who truly turn to him. Yet this woman was turning from being a “sinner” more readily than the Pharisee and most of his guests were willing to turn from sinful, religious pride. To be most ready for crossing cultural barriers in mission (the Book of Acts), we should begin crossing barriers near us, to experience and share God’s grace (his generous favor) to others around us.

That Jesus welcomes the woman’s gift—no matter what others think—reminds us of another theme in Luke-Acts: those who are initially objects of mission can become missionaries themselves. For the most part, Jesus chose as his first agents fishermen, a tax collector, and those of apparently nondescript professions rather than the more humanly obvious choices of priests or scribes. Peter, the “sinful man” (Luke 5:8); Paul the persecutor (Acts 9:13-15); and others become agents of Christ’s mission.

The Spirit empowering the apostles’ circle for mission at Pentecost (Acts 1:8) is also poured out on the Samaritans (Acts 8:17) and Gentiles (Acts 10:44-47) and all who are far off (Acts 2:38-39). Why? So all these groups can share in the apostolic mission of proclaiming Christ. Some who may begin as some sort of marginal minority within our circle of believers may be laying the foundations for future ministry. Cheryl Sanders, a pastor and professor of ethics at Howard University, has a valuable book called Ministry at the Margins: The Prophetic Mission of Women, Youth & the Poor. Her title catches one of the themes in Luke-Acts.

God does not usually start his activity where we expect or the way we expect. He does not need our wealth, status or power, because he does not want our pride. He often starts with the lowly and the marginal (Luke 1:51-53), pouring out his Spirit and surprising us with revival, just to remind us all that the power for his work comes from him and not from ourselves.

Craig Keener is author of commentaries on Matthew, John, Acts, Romans, 1-2 Corinthians, Galatians, and Revelation; his IVP Bible Background Commentary: New Testament, has sold more than half a million copies.

As an interracially married minister, ordained in an African-American denomination but currently president of the Evangelical Theological Society, I want to share some of what the Bible teaches about ethnic conflict and reconciliation. This is just an overview (what I can do in half an hour), and I am skipping here my personal stories (again, staying at about half an hour). But my observations here draw on what I have been speaking about in my classes and public settings for some 30 years. Thirty years ago most people were not listening 🙁 but I am trying again today: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r1PcBRqFph0

(If you want a one-minute video with just some thoughts about racial reconciliation, from my wife Médine, who is from Central Africa, and myself, a white guy from the U.S., see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqQSUfbNeU0)

Part 2 of Mike Licona’s interview with Craig regarding ancient biography (17.48 min’s). This one offers a good summary of Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OnztmnWOHTE

Kindle or hard copy on Amazon, ebook or hard copy on Christianbook.com

P.S., authors should do their best to communicate their intention, but inevitably authors get interpreted through the frameworks and categories of readers. My friend Bill Craig (William Lane Craig) interprets my friend Bart Ehrman’s interpretation of myself and some others here. 🙂

I’m going to talk about two kinds of leaders in Mark 10:42-45, but the discussion will make fullest sense if I spend some time in the rest of Mark’s Gospel setting the stage for this.

Jesus throughout Mark’s Gospel displays one kind of leadership. Some scholars like to play Jesus’s “Messianic secret” (his invoking silence regarding much of his ministry) off against his signs or glory. But they are envisioning the wrong dichotomy. Throughout the Gospel, Jesus is healing and delivering others, even at risks to himself. (His times with the marginalized would not commend him to the elite.) He is not seeking his own honor; his acts of healing are part of his being a servant to others. Jesus spent time with the disabled, and moral and social outcasts—he’s not looking to get the powerful to back his cause.

There are also other kinds of leaders in Mark’s Gospel. These include some of the scribes and Pharisees, whose confrontations with Jesus show them more committed to their stringent interpretations of Scripture than they are to the desperate human needs Jesus is meeting. Still more unlike Jesus are the Jerusalem elite, who flaunt and sometimes abuse their honor and power. Like tenants in the vineyard in the parable Jesus tells in Mark 12, these leaders forget that God allowed them to be caretakers. They do not want to relinquish their power over the vineyard of God’s people.

We should expect the disciples to be different. Jesus is training these relative nobodies to be leaders in his kingdom. Most of them are from modest or poor backgrounds; most of them were also probably not well-educated (although at least the tax collector should have had basic writing literacy). They were Galileans, whom Jerusalemites sometimes viewed as country bumpkins. They should understand that Jesus is about helping those in the greatest need, not about self-exaltation.

But soon the disciples, expecting places of honor in Jesus’s kingdom, begin looking like the other kinds of leaders rather than like Jesus. They try to protect Jesus from being bothered by children (10:15); other followers want to protect him from a blind beggar (10:48). After the disciples try to keep away the children, Jesus has to repeat a lesson he had already given his disciples about receiving children (9:36-37; 10:14-15)!

And before the lesson of 10:42-45, they become even deafer to Jesus’s message. After a rich man refuses to surrender his wealth for the kingdom, Jesus again reminds his disciples that the first will be last (10:31) and that Jerusalem’s elite will precipitate his death (10:33-34). Instead of contemplating this sobering warning, James and John immediately ask to be greatest in the kingdom (10:35-40). (After all, they were just on the Mount of Transfiguration with him and Peter, while the other disciples were failing in an exorcism below the mountain.) This ploy makes angry the other ten: James and John are butting ahead of them in line (10:41)! The disciples had already been debating among themselves who was the greatest, and Jesus had already responded that the greatest would be like a child (9:33-35). His message, however, has obviously not yet sunk in.

So Jesus gives the lesson in 10:42-45. Here he contrasts two forms of leadership. For the first, he speaks about the world’s way of power, exemplified by the “rulers of the gentiles” (10:42). (Keep in mind that, for Jesus’s Galilean disciples, gentiles did not exactly epitomize moral ideals.) This was the sort of raw power that allowed Pilate to hand Jesus over for execution or for the Jewish tetrarch Herod Antipas to have John beheaded (though both Pilate and Herod succumbed to others’ demands in these cases). By Galilean standards, Herod even seemed a “king” (6:14, 22, 25-27).

This differed from the ideal kind of rulership, the reign of God, his kingdom, proclaimed by Jesus (1:15). This divine kingship would someday be manifested in the glory that God’s people were expecting (14:25; 15:43), but it first came in a hidden way—the humble “secret” or mystery of the kingdom I’ve already mentioned (4:11-12). It is a kingdom that belongs to children (10:14-15), inimical to power based on wealth (10:23). And the language of king, besides the pseudo-king Herod, clusters in Mark 15, when his enemies mock Jesus as king of the Jews (15:2, 9, 12, 18, 26, 32) and crown him with thorns (15:17).

The rulers of the gentiles exercise authority in self-seeking, abusive ways (10:42). By contrast, Jesus exercises authority not like the scribes (1:22), but for driving out demons (1:27) and forgiving sins (2:10). He delegates this authority to his disciples—also to drive out demons (3:15; 6:7), waging war against the enemy kingdom of Satan (3:24-27).

In contrast to the power of gentile rulers (10:42), Jesus offers a contrasting paradigm (10:43-44). “This way of the gentiles—that’s not how it must be among you. Instead, whoever wants to be great among you will be your servant, and whoever wants to be first among you will be slave [doulos] of all” (10:43-44).Jesus uses power to heal the sick (5:30), not to help himself (15:30, 32; cf. Matt 4:2-4).

Unfortunately, this is not the first time Jesus had had to offer this lesson: he has to keep reminding them! In 9:33-34, the disciples had been discussing who was the greatest among them. Jesus then warned them in 9:35 that whoever wants to be first will be last and servant of all. Now again James and John had sought to be highest in the kingdom, and Jesus has had to repeat the lesson. Our habit of competing for honor or attention dies hard.

Yet Jesus is not offering mere abstract instruction. He is offering himself. And insofar as he is our hero, our model of greatness, humbling ourselves must become our ambition! Our Lord is greatest of all, having humbled himself most of all: though being divine, he humbled himself, taking on him the form of a servant, and became obedient to death, even the particularly shameful death on a cross—the ultimate humiliation. Yet God has exalted Jesus Christ as Lord of the universe! (Phil 2:5-11).

And so Jesus gets specific, in 10:45 essentially adding another passion prediction that brings them back to the subject that preceded the quest for greatness (10:33-34): Jesus, the Lord himself, must die. “For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many.”

Mark’s entire Gospel shows Jesus serving, a servanthood that climaxes in Mark’s lengthy passion narrative. “Ransom” (10:45) often meant the price used to buy someone from slavery. Jesus by his own life offers himself as a slave (10:44) to free us from slavery. We could not have saved our own lives for eternity, but Jesus does. In 8:37, Jesus asks what a person can give in exchange for their soul (antallagma psuchê). Here Jesus says that he gives his own life (psuchê) in the place of (anti) many. He gives his life in exchange for ours.

We whom God had graciously appointed as leaders—some of us from lowly backgrounds like the disciples—have a special privilege and opportunity to serve all the more. May we always remember our Lord’s model: for how can we ever serve as humbly as he has served us?

Around the year 2000, for the Eerdmans Lectionary commentary, I wrote on a reading for Pentecost Sunday, on Acts 2. Here is one paragraph that I wrote:

“After recounting the proofs of Pentecost, Acts focuses on the peoples of Pentecost: Jewish people from many nations serve as the first representatives of the gospel crossing all cultural barriers (2:5-11). Some have compared the list of hearers here with the table of nations in Genesis 10, updated into the language of Luke’s day. If so, this passage may reverse the judgment on the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11: as God once scattered the nations by dividing their languages, he now empowers his church to transcend those divisions. One of the activities of the Spirit in the rest of Acts is guiding the church to cross cultural barriers beyond its comfort zones (8:27-29; 10:17-20; 11:12; 13:2, 4). An expositor could easily apply this example to racial reconciliation, cultural sensitivity, crosscultural ministry, global mission, and to church unity today (Rom 15:16; 1 Cor 12:13; Eph 2:18-22).”

My family is interracial (I’m the only white member; my wife and kids are black), so you can tell where I would take this if I were preaching this weekend. (At craigkeener.org, I usually focus on Bible study resources, but I responded with my personal convictions on my personal Facebook page shortly after the murder of our Christian brother George Floyd, because the issue just comes too close to home.)

But I think I can rightly hope that I am not alone on this. Given what’s happening in the U.S. right now (I write this on May 30, 2020), racial reconciliation is a burning topic. Nor is the issue a new one (I mentioned my earlier article to highlight this point). Minorities within a culture know the perspectives of the dominant culture, because such perspectives pervade the culture; the dominant culture, however, is usually far less acquainted with the experiences of minority cultures, because they can live life without having to recognize these experiences.

But as Christians, we belong to one body. It is incumbent on us—and especially for members of the dominant culture—to listen to and learn from the experiences of our brothers and sisters, to be “swift to hear, slow to speak” (James 1:19). Some may want to ignore the pain of our brothers and sisters, using as an excuse hooligans who exploit protests as an opportunity to loot. But what hurts Christ’s body pains Christ the head, and those whose first loyalty is Jesus, who care about his heart, must care for one another, and stand for justice for one another.

I also wrote some of the material on Pentecost for the forthcoming lectionary commentary from Westminster John Knox, where I elaborated more extensively on the implications of the transformation of Babel in Acts 2. There I concluded: “The Spirit in Acts thrusts us across human barriers to honor our Lord among all peoples. The Spirit also empowers believers together, regardless of ethnicity, class, gender, as partners in this mission, equally dependent on God’s enablement. Perhaps it is time, like the first disciples, to pray for the enablement of God’s transforming Spirit.”

For fuller detail on Acts 2, see Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (4 vols.; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012-15), 1:780-1038; or, more concisely, Craig S. Keener, Acts (Cambridge NT Commentary; Cambridge University Press, 2020), 121-78.