Among some, the claim that Jesus was a refugee has become politically divisive these days, so I should point out that the title used in this analogy predates the controversy; it was my own observation, published in my IVP Matthew commentary in 1997 (pp. 69-70). How that should apply to details of contemporary political debates may be a legitimate question. Whether Christians should care about refugees and try to help them is not. Whether Jesus and his family actually had to leave their country because of political oppression is a debate only among those who question the historical authenticity of Matthew’s report. Having prefaced my comments with these remarks, I turn now to the pre-controversy Bible study I wrote back in the early 1990s and have only slightly updated.

Persian Magi were known for using stars and dreams to predict the future, and it appears that on this one occasion in history, God spoke to the Magi where they were looking. Although Scripture forbade divination, in this period many people believed that stars could predict the future, and rulers anxious about such predictions sometimes executed others to protect their own situation. (One ruler, for example, is said to have executed some nobles to make sure that they, rather than he, fulfilled a prediction about some leaders’ demise!)

So large was the Magi’s caravan in Matthew 2 that they could not escape notice; Matthew says that all Jerusalem was stirred by their arrival. The Magi had every reason to assume that a newborn king would be born in the royal palace in Jerusalem; but despite Herod’s many wives, he had sired no children recently. Herod’s own wise men sent these Gentile wise men off to Bethlehem, just six miles from Jerusalem and in full view of Herod’s fortress called the Herodium. They later fled Bethlehem by night, but the disappearance of such a large caravan would not go unnoticed for very long.

Herod acts in this narrative just like history shows us Herod was: he was so paranoid and jealous that he had executed two of his sons on the (false) charge of plotting against him, as well as his favorite wife on the (false) charge of infidelity. On his deathbed, he would execute another son, and leave orders (happily unfulfilled) to execute nobles (so there would be some mourning when he died; cf. Prov 11:10). A probably apocryphal report attributes to the Roman emperor the opinion that it was safer to be one of Herod’s pigs than one of his sons.

Contrasting the different characters in this account reveals striking ironies. Fitting a theme in Matthew’s Jewish Gospel, these Gentiles come to worship Jesus. By contrast, Herod, king of the Judeans, acts like a pagan king: like Pharaoh of old (and another pagan king more recently), he orders the killing of male children. Most astonishing to us, though, should be Herod’s advisors, the chief religious leaders and Bible teachers of the day: they knew where the Messiah would be born, but unlike these Gentiles they did not seek him out. Merely knowing the Bible is no guarantee that we will obey its message. (We should note, however, that the Sanhedrin, whom Herod uses here as advisors, was not very independent in this period; he had executed his opponents and replaced them with his political lackeys.) As in the parable of the sower, we ought to sow on all kinds of soil; sometimes God has plans for the people we least expect.

But notice also the other characters. The narrative repeatedly emphasizes “the child and his mother” as the objects of Herod’s hostility. Though this powerful king will soon be dead, he feels threatened by those who were at the time politically harmless. Undoubtedly able to use the resources provided by the Magi, however, Joseph’s family found refuge in Egypt, like an earlier biblical Joseph. Probably they settled in the massive city of Alexandria, where according to some estimates nearly a third of the city was Jewish.

Years ago, when I wrote my first commentary on Matthew, I wrote at this point that Jesus was a refugee: a baby in a family forced to flee a corrupt dictator, just like so many political refugees in different parts of the world today.

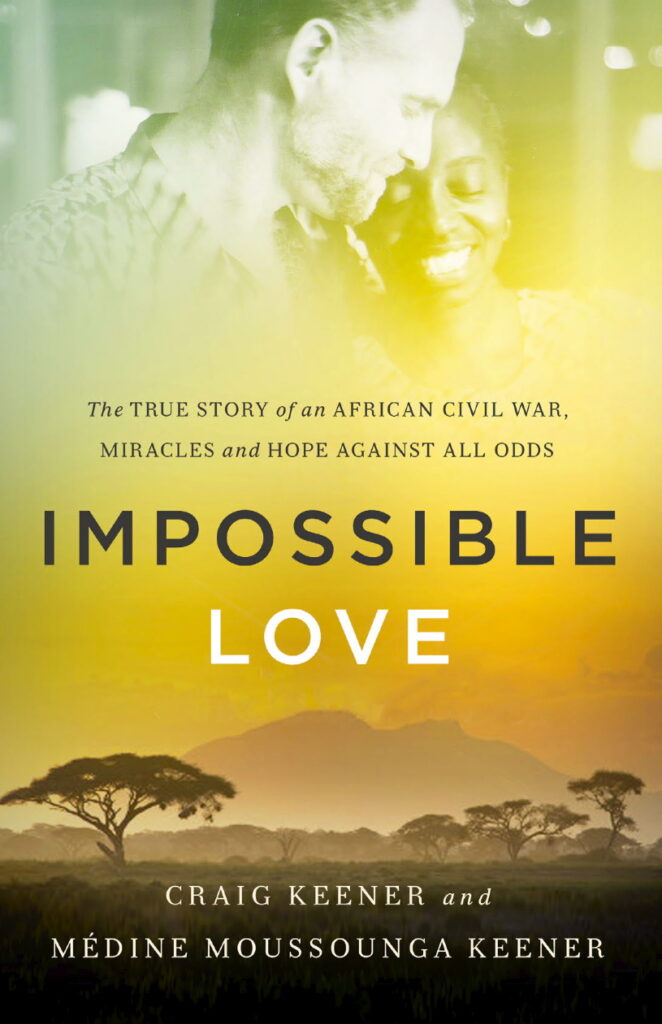

As I wrote it, I grieved for my dear friend Médine, whose country, Congo-Brazzaville, was at war. Later I learned that her town had been burned down, and did not know for eighteen months if she was alive or dead; if she was alive, however, she was undoubtedly a refugee, along with perhaps as much as a quarter of her nation. Still later I discovered that she had fled the town carrying a baby on her back and joining others in pushing her disabled father in a wheelbarrow.

When Médine read in my Matthew commentary that Jesus was a refugee, she found meaning in what she had experienced; Jesus had suffered what she had suffered. Médine is now my wife, and we have a happier life. But we cannot easily forget those who, like our Lord two millennia ago, face suffering because of others’ injustice.

The story of Craig and Médine together appears in Impossible Love: The True Story of an African Civil War, Miracles, and Love Against All Odds (Chosen Books, 2016). Craig S. Keener is author of a smaller commentary on Matthew with InterVarsity Press and a larger one with Eerdmans (The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary, 2009), as well as The Historical Jesus of the Gospels (Eerdmans, 2009) and Christobiography (Eerdmans, 2019).