Category Archives: Current issues

Ancient apologetics

3 minutes: ancient apologetics. How Paul was able to use Jewish apologetic arguments when engaging with ancient intellectuals. Also apologetics vs. skepticism today. 3-minute video clip by Acts scholar Craig Keener. For 23 free lectures on Acts, see http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/DigitalCourses/00_DigitalBiblicalStudiesCourses.html#Acts_Keener

Evangelical means different things

Some writers in the media have identified evangelicals more as a political movement than a spiritual one, and demeaned evangelicals as blind followers of Donald Trump.

This is an unfair caricature, and for one thing grossly underestimates the movement’s diversity. I offer further thoughts in

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/craig-s-keener/evangelical-subculture-ve_b_9295550.html

Was Paul really a Roman citizen?–Acts 16:37

Paul’s Roman citizenship. 13.4-minute lecture by Acts scholar Craig Keener. For 23 free lectures on Acts, see http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/DigitalCourses/00_DigitalBiblicalStudiesCourses.html#Acts_Keener

One body, many gifts

Half-hour message on Romans 12

Christians for Biblical Equality recorded this message of mine in 2005 at their conference. I am amazed to see that I was bald even back then. 🙂

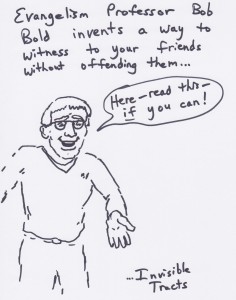

Reinterpreting syllabi? (cartoon)

Paul and the Jerusalem Council

Paul and the Jerusalem Council–Acts 15, and how Galatians 2 fits this. 9-minute lecture by Acts scholar Craig Keener. For 23 free lectures see http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/DigitalCourses/00_DigitalBiblicalStudiesCourses.html#Acts_Keener

Is it all right to call God Allah?

Some people today debate whether it is all right for Christians to call God “Allah.” Those within cultures that speak Arabic (or Hausa or other languages that use this title) have a right to discuss whether there might be inappropriate connotations in some of their contexts (or where it might be against the law). But from a purely language standpoint, nobody else should be debating it.

The English word “God” did not originate as a Christian title. Nor did the Greek word that we translate God, “theos”; that was used for pagan Greek deities long before the spread of monotheism in the Greek-speaking world. Canaanites called their chief god “El” and their gods “elohim” before the patriarchs could adopt these titles for the true supreme God. “Allah” in Arabic is related to the Hebrew term for God. It makes no more sense to prohibit Arabic-speaking Christians from using an Arabic term for God, understood in a Christian way, than to prohibit English-speaking Christians from using the term “God,” understood in a Christian way, even though we recognize that others could speak of other “gods” using the same English word, or that others who believe in one God might have a different understanding of this God. I am not entering into the debate here about what Muslims and Christians mean by God–there are some significant differences. But one either adapts existing language, which is usually how we translate, or uses a new loanword and explains it. (YHWH may be “untainted,” but even biblical terms for God such as Elohim and El and theos are not.)

In English we speak of Saturday without regard for it being named after the Roman divinity Saturn, or Sunday being named for the Sun (deity), or Thursday for Thor or the like. We are often very inconsistent in what we tolerate–usually tolerating more that is under our own nose than what is under someone else’s. What might be more fruitful is getting to better understand and communicate what God is like–getting to know His heart in Jesus Christ.

Paul and the Law

Scholars articulate a range of views concerning Paul’s approach to the law. A basic summary of my own current perspective (which surfaces at points in my small 2009 Romans commentary) might be as follows:

- Paul respects the law as God’s Word; this includes both the narrative and the legal material.

- Paul believes that the law was meant to teach right behavior (much of which is universal, though Paul does not usually spell out the hermeneutic that guides how he distinguishes those elements).

- Paul does not believe that the law was meant to transform the heart directly; rather it is meant to point/testify to the experience with the law’s God that transforms the heart.

- The law’s specific stipulations guided Israel in their setting (e.g., agrarian, in the promised land, etc.), but just as those stipulations required new forms of obedience for their day, so the fuller revelation in Christ takes on new forms.

- This fuller revelation in Christ, which Paul has undeniably experienced, has inaugurated (albeit not consummated) the promised messianic reign in a largely unexpected way (most dramatically, in a cruciform way), with equally unexpected consequences.

- This fuller revelation in Christ makes available (as a foretaste of the coming world) the life-transforming experience with God through the Spirit that fulfills all the principles of the law (thus, for example, the new covenant’s greater circumcision of the heart to which earlier physical circumcision merely pointed; or Jesus’s summary of the law’s heart as love).

- The law’s universal moral and spiritual principles, which God communicated to Israel in a specific context, can be recontextualized by the Spirit for all people of the new covenant, including ethnic Gentiles grafted into Israel’s heritage through following Jesus, Israel’s Messiah (here it must be acknowledged that we often lack consensus on what the universals are; I have offered elsewhere suggestions for discerning those; see e.g., http://www.craigkeener.org/how-i-love-your-law-ot-laws-in-context/; http://www.craigkeener.org/understanding-and-applying-ot-laws-today/; http://www.craigkeener.org/which-day-is-the-sabbath/).

- The law testifies to the way of a personal relationship with God, as evidenced in the lives of Abraham, Moses, and others; its heart is more about God and his covenant love (e.g., Exod 34:4-7) than about its stipulations (though those stipulations remained crucial as part of God’s covenant with Israel at Sinai).

- As part of Israel’s heritage and a continuing witness to the universal truth the Scriptures convey, even many of the law’s traditional stipulations remain valuable to those who remain Jewish by ethnic identity (e.g., Messianic Jews, such as Paul himself was, are fully within their rights to continue to express their Jewish heritage in this way).

- Paul believes that to approach the law as a list of duties (even ones joyfully undertaken) rather than a witness to the way of faith in (and thus personal relationship with) God (Rom 3:27; 9:31-32), or apart from the enabling experience of the Spirit (8:2), cannot transform the identity (more controversially, I am inclined to add, “and never could”; I believe that Paul saw Deut 30 and other parts of the law testifying to divine rather than human transformation of those who walk with God, with the new covenant developing this transformative empowerment more deeply in light of Jer 31:31-34 and Ezek 36:25-27).

- Treating the law’s stipulations as a means of demonstrating righteousness instead of depending on the divine favor and empowerment to which the law pointed in fact defies dependence on God’s favor and hence incurs condemnation. In this way, the law can even function as an instrument of divine judgment to those who miss God’s heart there.

Now, if you can figure out what such a set of views should be called, you are smarter than I. There are so many different permutations on various details on the scale between Luther and various New Perspective(s), with Reformed articulations often friendlier to continuing value for the law than some other views (especially Bultmann’s), that I find traditional ways of classifying views inadequate (even if they are necessary to provide some sort of handle on the spectrum).

I am noting this hastily constructed list because I am turning more of my attention back to Pauline studies now, and if I am wrong on some of these points, it will be helpful for me to learn that now before I publish more work on this subject! Nevertheless I remain certain that, given the range of perspectives now current on various details, there is almost no way to summarize a view without missing some nuancing valuable for this or that point of debate. For that I can only apologize in advance and hope to keep learning.

The faithless prayer meeting in Acts 12

2.5 minutes from Acts scholar Craig Keener.

For 23 free lectures on Acts, see http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_hildebrandt/DigitalCourses/00_DigitalBiblicalStudiesCourses.html#Acts_Keener