In the previous post, I emphasized Jesus’s teaching on preserving and, where possible, restoring marriage. Jesus used graphic language to challenge some of his religious hearers’ insufficient commitment to marriage. In doing so, however, he was not seeking to make matters worse for those whose marriages were being broken against their will. Indeed, as noted briefly in that post, these were the very people that Jesus was defending.

Here I will first raise a problem—a way of reading a verse that some have used to prohibit and even break up remarriages. I will then show from the context of Jesus’s larger teaching on divorce, and other New Testament interpretations of his teaching, that this first way of reading the passage takes Jesus’s point out of context.

When Jesus speaks of remarriage after divorce as “adultery” in Mark 10:11, what does he mean? When used literally, adultery means sleeping with someone who is married to another person, and/or sleeping with someone other than one’s own spouse. (Most of the ancient world gave more license to the husband so long as his paramour was single, but the New Testament does not allow this double standard.) Thus, if Dedrick is married to Shamika and sleeps with Shonda, that is adultery.

But Jesus here seems to be saying that if Dedrick divorces Shamika and marries Shonda, that is still adultery despite the official divorce; that is, he treats Dedrick as still married to Shamika. In other words, he speaks as if human, legal divorce does not actually end a marriage in God’s sight.

The question is: Does Jesus mean this literally, or is he simply using a graphic way of warning against divorce? I argue here that he is using a graphic way of warning against divorce—that he is using hyperbole, that is, a rhetorical overstatement to drive home a point. Keep in mind that the point of hyperbole is not so we can dismiss its message, saying, “That’s just hyperbole.” Rather the rhetorical and literary device of hyperbole is a way to challenge us to examine whether we are living up to its message. How we take this matters: strongly warning against divorce is not the same as denying that God recognizes the legitimacy of new marriages.

Like (but even more than) many of his contemporaries, Jesus used graphic hyperbole to communicate many of his points. Anyone who is not willing to recognize that a given teaching at least might be hyperbole, before examining it, needs to reimmerse himself or herself in Jesus’s teachings. A camel does not normally literally fit through the eye of a needle; scrupulous Pharisees did not normally literally gulp down camels whole; and we have no record of Jesus’s first followers moving any literal mountains. These were graphic ways of communicating a point.

Moreover, the literary context of at least one of Jesus’s divorce sayings involves hyperbole. Just before his teaching about remarriage and adultery in Matthew 5:32, Jesus warns that whoever looks on a woman to covet her sexually has committed adultery with her in his heart (5:28). I often tell my students that I am proud to see that none of them has committed this sin. How do I discern their innocence? The solution to this sin, which appears in the next verse, is for the transgressor to tear out his eye. In fact, nearly all of us recognize that command as hyperbole—a graphic way of underlining the point that we must put away sin. No sane reader will follow this command literally.

Further, it may be relevant that Jesus does not tell a woman married five times that she was married once and that all the rest of her relationships were adulterous. Rather, he says that she has had five husbands but the man with whom she lives now is not her husband (John 4:18). One could argue that Jesus is speaking literally in John 4:18 but figuratively in Mark 10:11, or one could argue the reverse; but one who affirms the authority of both texts cannot easily have it both ways. Further evidence shows which reading is likelier.

Matthew and Paul recognize exceptions to Jesus’s graphic statement. In Matthew, Jesus says that a man cannot divorce his wife and remarry unless the wife is unfaithful (Matt 5:32; 19:9). (Some try to make the exception here something narrower than adultery, but the Greek term is actually broader than, rather than narrower than, adultery. It is only the context that limits it even to adultery.) The basis for remarriage being adulterous would be that God did not accept the reality of the divorce (all monogamists recognized that a valid divorce was necessary for remarriage). Here, however, God accepts the reality of the divorce if the spouse was unfaithful.

Yet if Shamika is not still married to Dedrick, how can Dedrick still be married to Shamika? If even an explicitly guilty party is not married to their first spouse in God’s sight, we cannot say that God literally regards the first partners as still married, or that remarriage is therefore literally adulterous. That a true follower of Jesus should work to preserve their marriage is clear, but that anyone should break up remarriages as adulterous unions, as some suggest, is not.

Paul explicitly allows the believer abandoned by an unbeliever (someone who is not following Jesus’s teachings) to remarry. (Laws in Corinth treated marriage as a matter of mutual consent; the departure of either party legally dissolved the marriage.) When Paul says that the believer is “not under bondage,” or “not bound” (1 Cor 7:15), he uses the exact language of ancient Jewish divorce contracts for freedom to remarry. This is precisely what the language meant when people in antiquity discussed divorce, the issue that Paul addresses here.

We should note what the two clear exceptions have in common: in neither case does Jesus’s follower break the marriage covenant; it is broken by the other person. One person working hard can often lead to the restoration of a marriage, but it is not guaranteed; the partner has their own will and can still choose to do the wrong thing (1 Cor 7:16). Paul had to address a local situation that Jesus did not explicitly address. Today we might think of physical abuse as an analogous kind of situation where the abuser is the one breaking the marriage covenant. Beyond such extreme circumstances, however, we need to be very careful, recognizing that some people will take any excuse to opt out of responsibility for a marriage (such as burning the toast, as mentioned in the earlier post). Paul makes clear that we are expected to do our best.

Not only do the biblical exceptions suggest that Mark 10:11 includes hyperbole, but so does that very verse’s context. Jesus demands, “Therefore what God has joined together, LET no one separate” (Mark 10:9). The point remains that we must not break up marriages. Yet the wording shows that marriage is not indissoluble in God’s eyes; Jesus warns against breaking marriage, rather than arguing that it is impossible to break. That is, the context of Mark 10:11, like Jesus’s and Paul’s other teachings on the subject, shows that Mark 10:11 uses hyperbole.

Jesus graphically summons us to commitment to marriage. Yet to break up remarriages (the solution that some readers have argued) actually undermines his point. Moreover, Jesus is certainly not seeking to make matters more difficult for those divorced against their will, as some churches have done. Treating someone divorced against his or her will to “stand against divorce” can be like treating someone raped or murdered against his or her will to stand against those actions.

I recognize that short posts cannot address all situations; these two posts have explored principles, but pastoral counselors must apply those principles in a wide range of concrete situations. What I hope is clear is that the biblical issue is less about whether someone eventually remarries than about the need to be faithful to marriage to begin with. (From a counseling perspective, it is unwise to enter a new relationship immediately after a divorce even if one was completely faithful to one’s previous marriage; the wounded heart is too vulnerable and needs time to heal. But at this point the expertise belongs not to me but to pastoral counselors and related professions.)

The narrowness of the explicit exceptions reminds us, however, that Jesus wants us to value and be committed to marriage. The point of exceptions is that they must be a last resort (though of course someone in physical danger is probably already at that point). Counseling or therapy can often save marriages. But we need to recognize that just as prayers for healing are not always answered (everyone acknowledges, for example, that godly people are not immortal), neither are prayerful attempts to save marriages when they involve only one party.

Believers must do their best to preserve marriage, but we must not abuse those whose marriages have broken, especially if it was not their choice. Jesus warned some religious people: “If you had understood the meaning of these words—‘I desire mercy and not sacrifice’—you would not have condemned the innocent” (Matt 12:7).

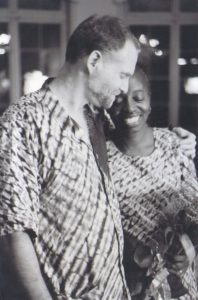

The book is our story, including Médine’s experience as a war refugee during the war in Congo

The book is our story, including Médine’s experience as a war refugee during the war in Congo