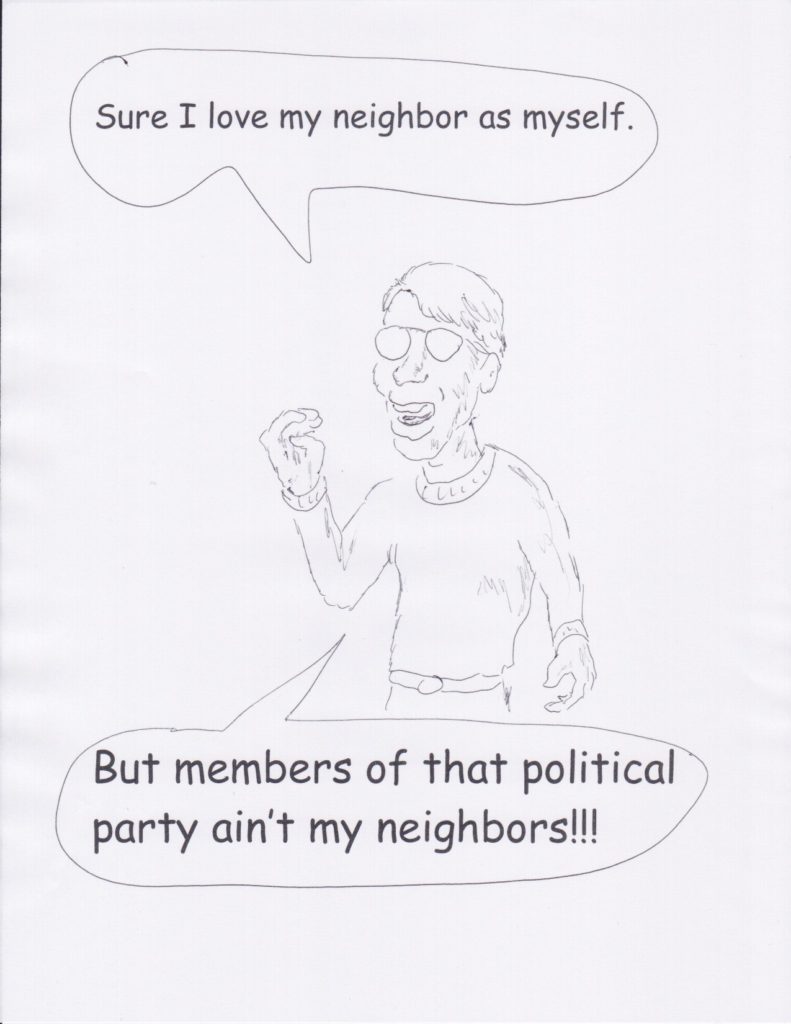

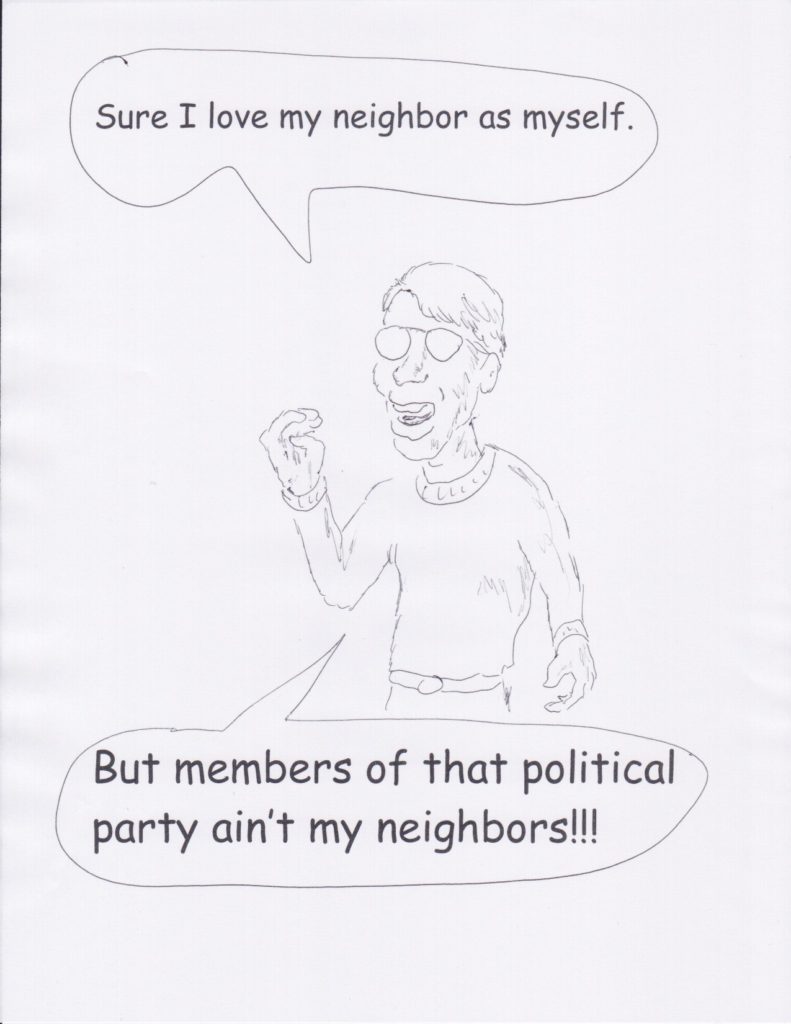

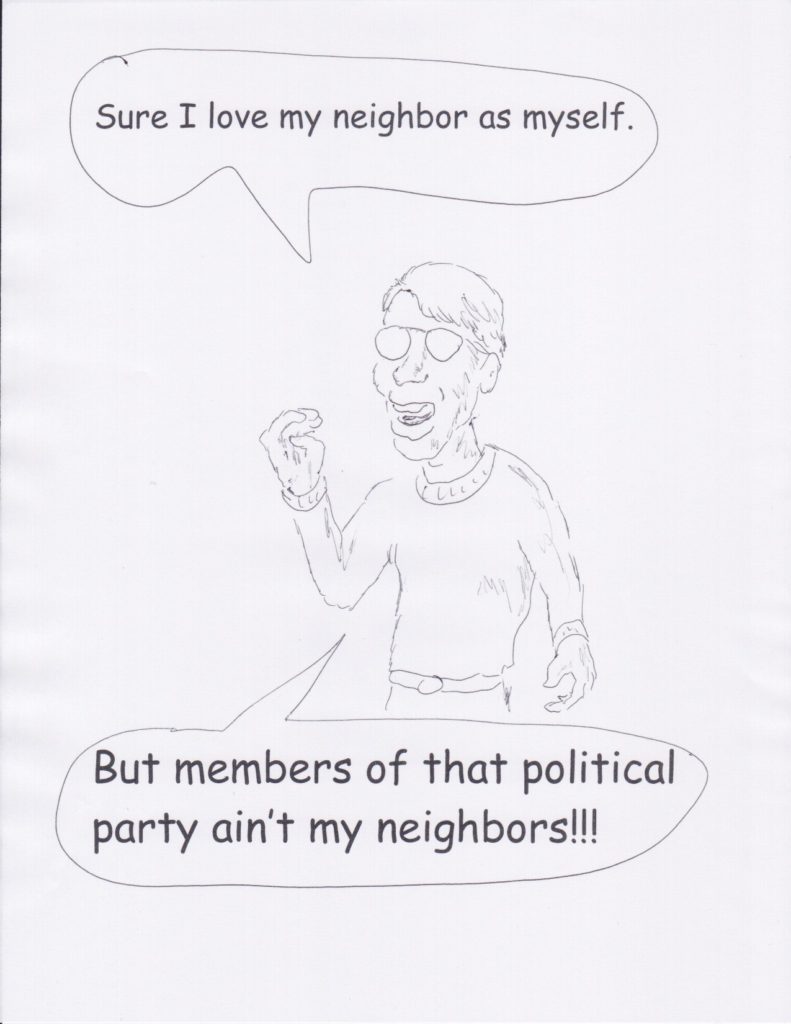

Love your neighbor but …

A survey of some key themes in James and its ancient setting:

If Pentecostals and charismatics have taught the church much about the Spirit empowering our speaking (treated in part A), Anabaptists (and early monastic orders) have taught us much about sharing.

If the immediate expression of the outpouring of the Spirit on Pentecost was prophetic empowerment, the longer-range impact was a new community of believers who walked together in their lives and shared one another’s needs.

Much of Acts 2:41-47 follows the following structure:

A 2:41 Successful evangelism (3000 converts)

B 2:42 Sharing meals, praying together

C 2:44-45 Sharing possessions

B’ 2:46-47a Shared meals, worship

A’ 2:47b Successful evangelism

Whereas the conversions in 2:41 responded to Peter’s preaching, the conversions in 2:47 apparently responded to the life of the new community. Peter’s preaching explained divine signs at Pentecost; but the sacrificial love that Christians showed one another was no less divine, no less supernatural.

At the heart of this display of unity was the costly expression of commitment to caring for one another’s needs, in 2:44-45. This sharing exemplified on a literal level what Jesus taught, sometimes on a hyperbolic level. For example:

In Luke’s Gospel, sharing possessions is actually a sign of repentance, an answer to the question what one must do to have eternal life (Luke 3:9-11; 18:18, 22). It does not earn eternal life, but it concretely evidences the reality of their turning to God. In Acts 2:37, hearers ask Peter what they must do, and his answer is more general: repentance and baptism in Jesus’s name (2:38). The sharing of possessions, however, soon follows as a fruit of this repentance.

In Acts, believers do not immediately divest themselves of all possessions and move onto the street at conversion. They do, however, sell what they do not need to live on, whenever someone is in need (Acts 2:45; 4:34). That this mutual caring is no fluke is clear because at the next corporate outpouring of the Spirit on the Jerusalem church—the next “revival” or “awakening”—sharing again takes center stage (this time, if anything, more emphatically; 4:32, 34-35). Caring for the needy continues afterward, although eventually the Twelve have to delegate this ministry to some other Spirit-filled ministers (6:1-6). Churches in one location also helped churches in another in view of impending famine—even though the famine was predicted to strike them as well (11:28-30).

Often people today pray for revival, thinking of the emotional benefits to individuals involved. But we might demonstrate to God better our commitment to such revival if we recognized up front what it might cost us. If we are ready to devote everything to God that he asks of us, it is clear that we really want revival. And when we are really fully devoted to God and dependent on his grace and power, revival has already begun, at least with us.

For one longer video on this topic, see http://www.craigkeener.org/radical-for-jesus-sharing-possessions-acts-241-47/

When Peter calls on slaves to submit even to harsh treatment (2:18), even beatings (2:20), is he endorsing slavery? Is he at least suggesting that we should embrace harsh treatment even when we can avoid it?

When we look at Peter’s sections addressed to slaves (2:18-25) and wives (3:1-6), we should consider what setting Peter was addressing. He was not addressing a setting of voluntary employees who could simply resign from work if they were being mistreated. He was not addressing women who might readily find different husbands who did not expect unilateral submission.

Peter’s advice to both slaves and wives belongs to his larger section of what are often called household codes, which ancients in turn often discussed in the context of civic management (2:13—3:12). Ancient writers often used such codes to express conventional expectations. For the sake of honoring the Lord (2:12-13), Peter urges compliance when possible with “every human institution” (2:13). This exhortation not endorse all these human institutions, such as slavery (2:18-25), monarchy (2:13, 18), or wives calling their husbands “lord” (3:6), as universal and eternal. It is not claiming that all these human institutions are permanent divine institutions. It is just calling on those in these settings to make the best of their circumstances.

Unless they earned enough money on the side to buy their freedom, slaves did not have much say concerning their slave status. Slaveholders often did eventually free slaves (though sometimes to preclude having to support them in their old age). A minority of slaves in the Roman empire achieved status and even wealth—even as slaves. But the legal authority to emancipate slaves lay solely with the slaveholders. Peter thus provides advice for how to bear up under a difficult situation that his addressees could not control, not how to address a situation that they could not control. This is the same approach taken by many ancient moral teachers, such as Stoic philosophers, who focused on what is in our power to control, rather than on what is not.

His comments to wives follow along a similar line. (The first word in Greek in 1 Peter 3:1 is homoiôs, which the NRSV translates, “in the same way.” It explicitly links the case of wives in 3:1-6 with the case of slaves in 2:18-25.) Addressing wives married to nonbelieving husbands (3:1), Peter urges them to win over their husbands by gentle and pure behavior. Illustrating such behavior, he uses the example of matriarchs such as Sarah who, functioning within the conventional expectations of her culture, obeyed Abraham. Sarah calls her husband “my lord” (Gen 18:12), fitting convention (though not always translated this way from Hebrew), just as others could so address various respected figures (Gen 18:3; 23:6, 11), including fathers (31:35) and brothers (32:4-5, 18; 33:13-14).

Yet just as Sarah may have done what Abraham said, so also Abraham did what Sarah said (Gen 16:2), once with God’s direct backing (21:12)! So why does Peter offer only the example of Sarah? Only Sarah’s example is relevant for these wives, because they cannot control what their husbands will do. Although the degree of power varied, in virtually all cultures Peter addressed, husbands governed their wives.

Yet we need not infer from this an endorsement of universal husbandly rule or lordship any more than we infer an endorsement of a universal practice of slavery in 1 Pet 2:18-25. Husbands ruling their wives is common through history, and we might expect as much from the effects of the curse (Gen 3:16). Yet we are not called to enforce the effects of the curse (e.g., requiring men to sweat when they work, or proliferating sin and death as much as possible).

Although Peter is mainly addressing those in subordinate positions in society (1 Pet 2:13), and ancient evidence suggests that women probably outnumbered men in the churches, Peter addresses husbands here as well. He summons them to care for and honor their wives (1 Pet 3:7).

In the case of wives, Peter is addressing the norm in his day, not the question direct physical abuse that he addressed with slaves (2:20). Unlike slaves, wives were not usually objects of beating in the regions that Peter addresses (1 Pet 1:1). Also unlike slaves, wives had options to safely remove themselves from such situations, if they arose; no laws compelled them to stay. Even Judean Pharisees, who normally recognized only the husband’s right to divorce, approved of intervening and making an abusive husband grant a divorce, thus freeing his wife to remarry. In other words, Peter is not advising against escaping such abuse for those with the freedom to do it.

Is it ethical to flee abuse? Scripture provides numerous examples. David fled from Saul, and Jesus’s family fled to Egypt to escape Herod. Even in cases of persecution for the name of Christ, Jesus allows fleeing (Matt 10:23), and his disciples normally did so when possible (Acts 14:6).

Let us be careful to use these passages the way they were meant to be used: to encourage one another’s faith in the face of difficult situations, not to make those difficult situations harder!

(This brief study addresses one subject only, not all the nuances of ancient slavery, the Bible and gender, etc. I originally wrote this as part of my preliminary contribution to an Anglican study group on 1 Peter at Lambeth Palace in London. The group’s final version will probably look different, so they should not be blamed for any oversights in my own!)

Some of us are sometimes tempted to think that God uses only ministers in the more technical sense. But God appointed ministries of the Word to equip all the saints for their respective ministries, to be lights in the respective places where they serve and live and study (Eph 4:11-13). “The gifts he gave were that some would be apostles, some prophets, some evangelists, some pastors and teachers, to equip the saints for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ” (Eph 4:11-12, NRSV)

Some of those other skills, such as health work and agriculture, address some of the very issues that Jesus cared about (as demonstrated by his healings and feeding multitudes). (That Jesus would have approved of doing what we can to provide outside of miracles is suggested by him telling his disciples, after the feeding miracle, to gather up the leftovers. That is, they wouldn’t need a miracle for their next meal.) Thank God for a prophetically insightful public administrator like Joseph, who was able to save many lives from famine (Gen 45:5, 7; 50:20). Priests became dermatologists when they had to examine people for what were believed to be contagious skin diseases (Lev 13:2-43). Somebody presumably took care of safety inspections (Deut 22:8).

Granted, in the Old Testament, we especially see the Spirit empowering God’s servants to prophesy or lead (e.g., Deut 34:9), and of worship worship leading (1 Chron 25:1-5) and other songs (1 Kgs 4:32; Song of Solomon). But we also see the Spirit filling Bezalel for artistic and architectural activity that honors God (Exod 31:3; 35:31; 36:1). The seven new officers of the church in Acts 6:3 initially must be full of the Spirit and wisdom for their work in administration and finance. God also gave Solomon special wisdom for judging (1 Kgs 3:9-28). Let’s not forget the Spirit filling Samson with superhuman strength (though the purpose was delivering Israel and not just winning prizes in competitions). God’s Spirit came on Mary to be a Mom (though in a special way for the virgin birth, which was for only one occasion in history).

Are you interested in biology, genetics and the like? Many discoveries in these areas can lead to improvements in health care. But of course the sciences hold their own interest. Proverbs 25:2 might speak of those who had leisure (i.e., not farming or other responsibilities) to seek knowledge: “It is the glory of God to conceal things, but the glory of kings is to search things out” (NRSV). (Even though we will never run out of hidden things, Deut 29:29.) Solomon had a passionate interest in biology and its applications; this was part of his God-given wisdom: “He spoke about plant life, from the cedar of Lebanon to the hyssop that grows out of walls. He also spoke about animals and birds, reptiles and fish” (1 Kgs 4:33, NIV)

There are plenty of military officers, though this was closer to their calling and empowerment in Old Testament periods where God’s purposes were closely tied to a nation (in Acts, we see many following the Lord but not so much specifically because of them being in the military, since the Roman military was not used only for just wars and certainly not for holy ones).

Even for other kinds of subsequent ministry, God used people’s various backgrounds as models for what they would do, such as shepherds (of sheep and then people), fishers (of fish and then people), accountants (tax collectors), scribes (Matt 13:52), carpenters, and the like. (Pastoral counseling counts as a pastoral/shepherd gift; cf. e.g., Ezek 34:2, 4.) (If plumbers and aeronautic engineers don’t appear on this list, it is because they didn’t exist in the biblical cultures yet. Only rich people had indoor plumbing, and hiking up the Acrocorinth, which I got to do once, was the closest anybody got to physical space travel.) Paul, of course, was sometimes bivocational as a leather worker (or tentmaker, depending on how you translate that); given what we know about this profession, that probably included sales also.

These are just a sample of the sorts of callings that God used, partly limited by the range of examples available in antiquity and partly because I thought these examples should suffice. (I could have listed many more). Further, many other callings are implied; our advanced economies and information technology allows us to specialize in ways not possible in antiquity. Community concerns for law enforcement, sanitation, and the like were handled differently but were matters of concern then as now. Given ancient values on hospitality and the making and selling of textiles even from homes, the polite behavior we expect in service industries was probably shared more widely in the culture.

So if your particular area isn’t in the list, don’t feel like it shouldn’t be. Obviously there are some spheres in which Christians cannot work, such as drug dealer or pimp (gangster boss Mickey Cohen, converted in a mid-twentieth century evangelism meeting, didn’t persevere in faith when he realized it would cost him his profession). But for the most part, God uses us in a range of professions, always in our witness for Christ and often even through the ways we serve through the profession itself.

Those of us who are called to use Scripture to equip the saints for their ministries (Eph 4:11-13) should remember this and encourage people in our congregations to flourish in their range of professions.

A conflict arose between the Hellenist and Hebrew Jewish followers of Jesus in Jerusalem in Acts 6:1. Most of the Hellenists spoke only Greek, having originated in the Diaspora. They included “Cyrenians, Alexandrians, and others of those from Cilicia and Asia” (6:9). These immigrant Jews remained loyal to the temple; most settled in their ancestors’ homeland precisely because they retained respect for its institutions and customs. This conflict in the church thus pitted local Judeans against immigrant coreligionists.

Today we read about conflicts between local people and immigrants in many places, and it is helpful to understand that such conflicts are not new. (Lest I be accused of simply pandering to the news cycles, I started with the biblical text before and during the writing of my Acts commentary, published in 2012-2015, and only after my initial exegesis did I consider analogies and applications.)

Analogies today can help make their predicament in the text feel more concrete. For example, many people from former French colonies have migrated to France and found less opportunity there than they had expected. (A closer ancient parallel to that in the first century would be the many provincials who settled in Rome, but that would be background for a different lesson.) Some, in fact, have found discrimination, something that my wife experienced during her education in France (though she also received great blessings from others there). Or we may consider Latino/a immigrants in the United States, some even with ancestral ties to parts of the U.S. that were once part of Mexico. (That was nearly two centuries ago—about twice as long as a Roman general had deported Judeans to Rome before the scene in Acts 6.)

Any such analogies have weaknesses; boundaries within the empire were porous for travel, for example, but those who were not indigenous to a city could remain “resident aliens” rather than citizens for generations! The analogies do, however, help us to feel more concretely the sorts of feelings reflected in Luke’s description of the text, and that he might have expected his audience to feel. Much of Luke’s audience probably lived in urban areas with significant populations of resident aliens. The churches would include a mixture of both resident aliens and long-time citizens, with the former probably predominating (at least in Roman colonies, where most Jews and Greeks were resident aliens). Because many were gentiles and all lived in the Greek-speaking Diaspora, however, they would probably identify first of all with the Hellenists rather than the Hebrews.

In the Jerusalem church, the immigrant widows complained that they were not receiving their fare share of the community’s care for needy widows (6:1). Back then, most women could not earn very much, and most widows were dependent on their social networks for support. Based on biblical teaching about caring for widows, Jewish communities provided for their own widows. But in this period, the support seems to have been local, through relatives or local synagogues. But Hellenists, some of whom settled in Jerusalem in old age, probably had a disproportionate number of widows. Certainly they had fewer local relatives to support them. Not surprisingly then, Hellenist widows received less support. And, not unlike today, problems from the wider society also could impact the church.

Luke emphatically favors concern and respect for widows (Luke 2:37; 4:25-26; 7:12; 18:3-5; 20:47; 21:2-3; Acts 9:39-41). At the same time, his term for their “complaining” is not a positive one, either in his work (Luke 5:30; 15:2; 19:7; cf. 12:13) or in biblical precedent (see Exod 16:7-9, 12; 17:3; Num 14:27, 29; 16:41; 17:5, 10; Ps 106:25). If the term suggests that their approach to the problem was less than ideal, perhaps they did not try to raise the problem with the leadership (not that leadership always listens).

In whatever manner we construe their complaining, however, it soon becomes clear that the apostles consider their cause to be just (or, at the very least, not worth dividing over, Acts 6:3).

Even though Luke does not explicitly identify the Galilean apostles among the “Hebrews” against whom the widows complained, the apostles were in charge of the food distribution program (Acts 4:34-35), so they bore ultimate responsibility for solving the problem. Luke may use the massive growth of the church (6:1a) to help explain how the apostles had missed the problem, but what is clearer is that they move quickly to remedy the situation.

The apostles hand over the food distribution program to others. Matters had grown too large for personal attention even to each of the sick who needed healing (Acts 5:15-16; cf. Luke 5:15-16, 19; 8:19; 19:3), so the apostles follow Jesus’s example and delegate (Luke 9:1-2; 10:1-2). (One may compare how inappropriate complaints in Num 11:1 nevertheless led to the appointment and Spirit-filling of seventy elders in Num 11:16-17. The apostles, however, most clearly evoke Exod 18:19-21; Num 27:18-20; and Deut 34:9.)

These were not simply any new leaders, however. Although only a minority of Judean residents had Greek names, all seven of the new leaders have Greek names (Acts 6:5). They are not only Hellenists, but very conspicuously Hellenists. The community selected (6:3, 5) and the apostles blessed (6:6) members of the offended minority group.

But again, these were not merely any members of the minority group, but those whom both groups could trust to put God’s work first and to act fairly (6:3). The church was growing in cultural diversity and needed culturally diverse leaders (cf. 13:1); whoever was truly full of the Spirit and wisdom could be trusted in the other matters. (Genuine fullness of the Spirit needs to be spiritually discerned, but it is not limited by culture or ethnicity.)

Why appoint diverse leaders? Perhaps for the peace of the community. Or perhaps because those culturally closer to the situation could more readily see needs that Hebrew “blind spots” had missed. Or perhaps both. In Acts 8, the culturally sensitive Hellenist Philip paves the way for Peter’s ministry to Samaritans and Gentiles. In Acts 15, the church seeks a consensus solution, at least sufficient for working agreement.

I know from experience that if I state applications here that I think should be obvious, some will protest and accuse me of mixing my opinions with Scripture. So instead, I offer an invitation. Pray about what I have highlighted in this passage. Ask the Lord what he may want you to do about it.

When brothers and sisters in Christ complain about how their people have been treated, we should listen.

“Weep with those who weep” (Rom 12:15)

“If one member of Christ’s body suffers, then every other part suffers with it” (1 Cor 12:26)

In the past, U.S. crimes against humanity include the slaughter and displacement of Native American peoples and participation in the African slave trade that decimated cultures and in which perhaps a third of the captives died on the transatlantic voyage. Thank God for those who stood up against it.

Most people today say, “We would have stood against such abuses.” But how often do we look the other way today?

“If we had lived back when our ancestors did, we wouldn’t have killed the prophets like they did” (Matt 23:30)

The twentieth century witnessed genocide after genocide: the German genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples (1904-1908), the Ottoman extermination of Armenians in the next decade, the subsequent Nazi extermination of millions of Jews (along with others, including Roma people), mass murders under Stalin, Mao, Idi Amin and Pol Pot. The world cried, “Never again!” after the genocide in Rwanda, even though many people knew very well that it had simply spilled over into Congo, eventually leading to millions more deaths. (Cf. my article https://www.evangelicalsforsocialaction.org/foreign-policy/we-cannot-say-we-did-not-know/.)

If we had lived back when our ancestors did, would we have spoken for justice? We do live in a time like our ancestors. Documented ethnic and religious cleansing is going on today, for example in parts of Nigeria and Central Africa, in multiple countries.

Proverbs 24:11-12 (NRSV):

“If you hold back from rescuing those taken away to death,

those who go staggering to the slaughter;

if you say, “Look, we did not know this”—

does not he who weighs the heart perceive it?

Does not he who keeps watch over your soul know it?

And will he not repay all according to their deeds?”

God have mercy.

Roe vs. Wade is in the news again. For anyone who doesn’t know, that’s the case that legalized abortion in the United States (although “Jane Roe” herself later came to oppose abortion).

The legality of abortion is a volatile issue, but one in which Christians, and others who believe that life is a basic human right, have an important stake. Beyond and distinct from its legality, which tends to dominate headlines, its morality is an issue that many families, Christian or not, must sooner or later confront.

Here I speak outside my expertise as a biblical scholar. Although I believe that I am correct in my analysis (that is, I genuinely believe my beliefs), subsequent generations often provide clearer perspectives than those writing in the thick of cultural debates. That limitation is, however, true for all of us, so I offer my best thoughts here. If I fail to persuade some readers, I hope that I will at least help them to consider why many who hold my position do so with ethical integrity and concern for justice.

Not just a partisan issue

I have openly opposed the current administration’s stance on immigration. I have written about biblical teaching on care for the poor; defended the full participation of women in ministry; and advocated for racial justice. Most of my writing specifically about social justice sounds, in a U.S. context, as if I am left of the political center, although in none of those posts have I advocated for or against any political party.

It is, however, concern for justice, not a connection to any political party, that drives my interest. Thus I would like to highlight a justice issue that I think that many of those who tend toward the political left need to reconsider. Of course, we need to care about the welfare of the mothers, and if abortion laws ever change, we will learn how committed to life those on the political right really are. Indeed, genuinely prolife commitments ought to show themselves now in costly commitments to nutrition programs for impoverished mothers globally (nutrition, malaria and so forth affect fetal development and mortality). Yet how can we not also care about the unborn if (as suggested below) we genuinely acknowledge them as live human beings?

This post is about abortion, but it is not about political parties and still less about individuals who have had abortions. Regarding individuals, Scripture is abundant in its teaching about grace and forgiveness. It is not even prolife to speak about forgiveness in cases where the mother’s life was at stake. Other cases involve wrestling with tragic situations or someone aborting a fetus before coming to the belief that this was a live human being. There are other cases where the moral dimensions of the decisions are more conspicuous.

The point is not about political parties or about individuals who have had abortions. It is whether we can help more people to recognize the value of human life even in the womb, so that together we can seek alternatives that affirm the value of every human life.

Limited Biblical Material

I have not written much about caring for the unborn, not because I think it unimportant but simply because as a biblical scholar I don’t have as much to work with textually. When I don’t speak as a biblical scholar, I don’t speak from my own expertise. Of course, we cannot limit ethical and moral reasoning to specialists in particular areas, so my limitations do not preclude me from speaking out. They just mean that you should take my limitations into account here, as you should take into account the limitations of the vast majority of people who are currently speaking about the issue.

To engage in intelligent discussions in ethics, we may have to reason with others about a range of issues such as nuclear weapons, social security, gun control, civilian casualties through smart bombs, market economies, and a host of other issues not directly addressed in the Bible. That the Bible does not directly address an issue does not exempt us from sometimes needing to consider the ethics of such situations. In fact, among issues not addressed, I think this one is clearer than most. (Again, some other issues, such as sacrificial care for the poor, are crystal clear in the Bible, though the most effective means of such care in modern economic contexts are often debated.)

Then again, the Bible’s lack of more specific attention to abortion is not completely surprising. Abortion wasn’t much of an option in ancient Israel; it was more of an option in the Roman empire, but, like direct child abandonment, seems to have been rare enough among Jews and Christians to not have come up in the New Testament.

Ancient Christian teaching

Among northern Mediterranean gentiles, however, abortion was enough of a cultural issue that it does appear in some early Christian documents. One cannot accuse these precedents of politically partisan U.S. biases.

Note for example the Didache, probably from the late first century, and thus perhaps contemporaneous with some of our New Testament. It often offers great advice, such as: welcoming in trust those prophets who come to you, but: if they ask for money, they’re false prophets!

Most relevantly here, it warns: “Don’t murder! Don’t commit adultery! Don’t molest children! Don’t have sex with someone you’re not married to! Don’t steal! Don’t practice sorcery and witchcraft! Don’t kill a child by abortion or kill one already born!” (Did. 2.2). Or compare the late first- or early second-century Epistle of Pseudo-Barnabas: “You shall not take the Lord’s name in vain. You shall love your neighbor more than your own life. You shall not abort a child nor, again, commit infanticide” (Barn. 19.5, trans. Holmes).

Neither of these works is part of the biblical canon (a fact for which I am particularly grateful in the case of Pseudo-Barnabas), but they do show us that from an early period Christians in the gentile world grappled with the question.

Much stronger is a later second-century work: “those women who use drugs to bring on abortion commit murder, and will have to give an account to God for the abortion” (Athenagoras Plea 35, trans. ANF). Near the end of the second century, Tertullian insists: “For us murder is once for all forbidden; so even the child in the womb, while yet the mother’s blood is still being drawn on to form the human being, it is not lawful for us to destroy. To forbid birth is only quicker murder. It makes no difference whether one take away the life once born or destroy it as it comes to birth. He is a man, who is to be a man; the fruit is always present in the seed” (Apology 9.8, LCL trans.). In Sibylline Oracles 2.281-82 (which may be a Christian interpolation), abortion merits eternal punishment.

Such sentiments reflect the prevailing Jewish view of the time as well; note for example the first-century writer Josephus: “The Law orders all the offspring to be brought up, and forbids women either to cause abortion or to destroy it afterward; and if any woman appears to have so done, she will be a murderer of her child, by destroying a living creature, and diminishing humankind: if anyone, therefore, proceeds to such fornication or murder, he cannot be clean” (Against Apion 2.202, trans. combining Whiston and LCL).

Or Pseudo-Phocylides: “Do not let a woman destroy the unborn babe in her belly, nor after its birth throw it before the dogs and the vultures as a prey” (Ps.-Phoc. 184-85; trans. OTP). (The Diaspora Jewish philosopher Philo, by contrast, seems to begin life only once the fetus is fully formed; Philo Special Laws 3.108-9.)

Examples could be multiplied, but rather than reinventing the wheel I simply refer those interested in the question to, for example, Michael J. Gorman, Abortion and the Early Church, who shows the church’s consistent position in its first four centuries. Those interested in a consistently prolife treatment from a justice-emphasizing ethicist should also look at Ronald J. Sider, The Early Church on Killing (addressing early Christian pacifism as well as rejection of abortion).

A fetal-fatal justice issue

Scripture may not address abortion explicitly, but if one grants that the fetus is a live human being, the moral principle involved seems fairly clear, at least to me. A key biblical expression of justice is to defend the weak and the vulnerable; who could be weaker than an infant, and especially an infant still in the womb?

Perhaps some oppose abortion simply because that position is considered “conservative.” Most Christians who oppose abortion, however, do so out of a sincere commitment to justice. Now, many are inconsistent in what sorts of justice they argue for; many ignore many genuine justice concerns advocated by the left. This inconsistency, however, does not justify critics on the left simply dismissing concerns about justice for the unborn.

Since nearly all of us believe that it is wrong to kill human beings, at least those who are not seeking, individually or corporately, to harm us, the key question of abortion’s morality is whether the fetus is a live human being. Here I reason less as a biblical scholar because biblical evidence is limited, but there is biblical evidence. For example, just as mothers attest babies kicking in their womb today, John the Baptist could leap for joy in his mother’s womb (Luke 1:44); the Spirit of God was already at work in him (cf. 1:15).

Believing that the fetus is a live human being is the key reason why many of us Christians oppose abortion. A prochoice professor friend with whom I once dialogued about abortion wanted to exclude from discussion the question of whether the fetus was a live human being. He said that raising that question was cheating, because it was designed to immediately end the argument. I responded that it is instead the very point that the argument is about; if the fetus is just extraneous tissue, there is no legitimate reason to oppose abortion, and few people would object to it. If, conversely, the fetus is a live human being, then deliberately killing that fetus is killing a human being.

I am a biblical scholar, not a biologist, but we have to make ethical decisions based on the best information available to us. In this case, the unborn child is not only genetically human, but he or she is a human genetically distinct from the mother.

Some of the more cogent objections

Granted, although the fetus is alive, it remains dependent on the mother until birth. Nevertheless, dependence can be an arbitrary criterion for personhood; indeed, medical technology has permitted fetal viability at a younger and younger age. Moreover, unlike infants of some other species, human babies remain dependent on others for survival even after birth.

Further granted again, there are legitimate debates as to when personhood begins. The majority of fertilized eggs spontaneously abort before a mother knows that she is pregnant. If all embryos within the first two weeks are persons, the majority of heaven’s (or on some views, limbo’s) human population could well be embryos that never saw the light of day!

But simply foreclosing the question of personhood’s beginning by declaring life to begin at birth or at fetal viability is not satisfactory. Development at, say, thirteen weeks, the end of the first trimester, is considerably beyond a two-week embryo. The fetus is now kicking, opening and closing fingers with distinct fingerprints, and more than two million eggs already reside in her own ovaries. By nineteen weeks, she may hear and respond to her mother’s voice. By twenty-two weeks (about five months), she looks much like she will after birth, although much smaller. Whatever the particulars, we can at least be certain medically that the fetus is human and genetically distinct from the parents.

Further granted, U.S. law does not directly commit or endorse abortion; it simply allows it. This differentiates the issue from any injustices directly perpetrated by a government. Thus some who believe that abortion is wrong do not believe that the government should be involved in restricting it. Many of us do acknowledge areas where we believe certain behaviors wrong yet do not advocate legal restrictions (such as, for example, consensual but casual sexual intercourse).

Nevertheless, should not the political left, which often seeks to regulate even details of interaction to reduce pain to the emotionally vulnerable, seek to protect the most vulnerable and voiceless persons of all (Prov 31:8)? If we would oppose a law that permitted the execution of one-year-olds or ninety-year-olds based merely on the general vulnerability of their age, should we not also stand for justice for the unborn? (Again, I speak to the U.S. situation, where citizens are granted a role in shaping the government; in societies where citizens lack such a role, they may be limited to addressing justice within their own voluntary communities.)

Many markers of human development have ambiguous or amorphous boundaries. For example, brains are not fully formed even in adolescents (and adolescents are definitely fully human; I love ours). The rational part of the human brain may reach the apex of its development somewhere around age 25; after roughly age 30, it begins to decline (woe is me!)

Happily, no one limits personhood to the late twenties, but a (very) few may start it after infancy. Thus Princeton University ethicist Peter Singer, for example, permits infanticide. Those who treat birth as an arbitrary criterion for personhood may either treat abortion as a form of prenatal infanticide or infanticide as a form of postnatal abortion. Some appeal to past legal precedent to deny the fetus’s personhood. The judiciary’s track record of shifting biases, however (consider, for example, the periods in which many members of the Supreme Court were slaveholders), does not engender confidence in mere legal precedent as a determinant for morality. (The same may be said, of course, for public opinion in general.)

Not just a left-right issue

Again, most of my posts that have addressed social justice have supported issues more often emphasized by the left than the right (“left” and right” being defined by the usual polarized U.S. political categories). In this case, it looks to me like the left and the right have matters backwards.

The U.S. political right tends to emphasize freedom from government interference, so one might expect them to be prochoice. The U.S. left tends to emphasize defending human rights, and therefore we should expect them to champion the vulnerable in the womb. What human right is more urgent than right to live?

It looks to me like a freak of historical development that in the U.S. the right is prolife and the left is prochoice. (We all, of course, have our own historical and cultural contingencies.) But it seems to me that whether we tend to favor the right or left on other issues, if our allegiance is to justice rather than to a particular party, we should celebrate what supports the right to life.

Prolife preaching

For better or for worse, only once over the years have I addressed this issue from the pulpit. This is partly because I like to preach expository sermons and not a lot of passages lend themselves to an expository treatment of abortion.

I was an associate minister speaking out on a matter where it would have been risky for the senior pastor, who supported my plan to address the issue, to speak. One member of the youth group was pregnant by another member of the youth group. The young man’s mother wanted the young woman to abort, but the young woman wanted to keep the baby, and the pastoral staff agreed with the girl’s right to do so.

I spoke about King David killing Uriah to cover up David’s sexual sin, and how we still sometimes take life to cover up our behavior—sometimes by abortion. If this thought scandalizes you, you would be right to imagine that it scandalized a lot of people that day. My guess is that a strong majority of that congregation’s members were Democrats. But as I noted explicitly, I was not advocating a political party. I was addressing a moral issue, no less than when I (more often) challenged people to sacrifice materialism and share their resources with the needy. I probably faced more hostility that week than any other. (Happily this congregation was very forgiving and liked me again the next week.)

But if truth is not partisan, we cannot limit our preaching based on what sounds most palatable to a given setting—even if it must be communicated as graciously as possible and balanced with a lot of preaching on other issues of justice as well.

Conclusion

The fundamental question that makes abortion a moral issue is whether the fetus is a live human being. If the fetus is a live human being, then should we not seek ways to protect it the way we would insist on protecting every other human life? If feticide takes a human life, then fifty or sixty million abortions in the U.S. since Roe vs. Wade is a serious and pressing justice issue, one of the most serious and pressing moral issues of our day.

Because I believe that the fetus is a live human being, I want more people to recognize the value of human life even in the womb. May we together, whether from the right or from the left, seek alternatives that affirm the value of every life.

This post is in response to U.S. attorney general Jeff Sessions citing Romans 13:1-7 with respect to taking children from their parents at the border.

To be fair, the larger context of his statement is that nations need to be able to legally protect their borders. But the larger, larger context is response to the issue of separating families. Although this post will touch on biblical thoughts related to immigration policies (which will not be resolved here), it is the attorney general’s appeal to Scripture that has invited my wading into the issue.

(Also, up front about me: my wife and kids are legal immigrants from Africa. All came from very dangerous situations, but given the limited number of refugees brought into the U.S. each year, probably none of them could have come as refugees. As of two years ago, the estimated total of involuntarily displaced persons globally was 65 million. The U.S. currently has a cap of 50,000 refugees allowed per year, which would be just over 0.08 % of the total. In the special circumstances of 2016, Germany admitted perhaps ten times that number, mostly from the Middle East.)

But is there biblical precedent for separating families at borders?

Well, sort of: when Abram entered Egypt as an economic migrant or refugee, Pharaoh took Sarai from him (Genesis 12:10-16). God judged Pharaoh’s household for what Pharaoh did to God’s servants (12:17). Some families separated at the U.S. border today might also be God’s servants.

Obeying the Government in Romans 13

But the attorney general was referring instead to Romans 13:1-7. Unfortunately, there is plenty of precedent in church history for governments exploiting this passage to justify conformity to laws that they did not have to create or apply the way they did—including by slaveholders and the Nazi and apartheid regimes.

I am not implying moral equivalence with Hitler’s regime. I am just saying that quoting Romans 13 does not prove its applicability for every situation. Paul wrote that lengthy (paragraph-long) admonition to just one church—the one in the capital, where Christian witness and relations with the imperial government were most at stake. There had also been recent unrest about paying taxes. Add to that unrest in Judea, which in just over a decade would break out in war. It already had a number of other Jews trying to explain to the government that many Jews were loyal and not about to start a revolution.

Speaking of revolutions, the British applied Romans 13 differently than the colonists during the States’ War of Independence. (I personally think the British had a better case than does the attorney general. But now, aside from stepping outside my expertise, I may be getting too controversial …) For further comments on the proper context of Romans 13:1-7, see especially the comments of Wheaton College professor Lynn Cohick (soon to be provost/dean at Denver Seminary and president of the Institute of Biblical Research) in USA Today.

When I was a young Christian, my father at one point forbade me to talk further with my brothers about the Bible. When I tried to persuade him of his need to accept Christ, he said I was disobeying the verse that says to honor one’s parents. The Bible said to obey one’s parents. What was I to do? I felt guilty either way, but chose what I thought was the lesser of two evils. I met with my younger brother Chris to disciple him when my parents were asleep. I kept attending church and sharing Christ on the street despite being aware of my father’s displeasure. I wish I had understood back then that Jonathan and Michal were right to protect David from their father Saul, who wanted to kill him. My father and I eventually had a wonderful relationship. But I share this account reluctantly (and for the first time publicly) to point out that sometimes we have to disobey authorities, though it must be only when absolutely necessary.

The Bible and immigrants

There are more complex issues about immigration, Scripture, and security that I cannot address here, but I will survey some Scripture before going on to questions of application.

God commanded his people to welcome and care for foreigners (see especially Lev 19:34; 23:22; Deut 10:18; 14:29; 24:14, 17, 19-21; 26:13), even embracing as “citizens” (members of Israel) those willing to become part of their people (Num 9:14; 15:14, 16, 26, 29-30; 19:10; 35:15; Deut 1:16; 26:11; 31:12). (Thank God: this provides some of the Old Testament basis for gentiles being grafted into God’s people in the New Testament. Any of us who are ethnically gentile should appreciate God’s kindness in welcoming us as fellow citizens with his people—Eph 2:19.)

What might apply to economic refugees might apply even more to refugees from violence, such as the family of Jesus traveling to Egypt to evade Herod’s brutal regime.

The hard part: how does this apply to public policy?

I will offer some suggestions about what I think, but a reader who protests, “You are outside your expertise!” would be correct. We all do our best to apply the Bible as wisely as possible. I am doing my best in this section, but this is not where my qualifications lie.

Security issues differ today from those in ancient Israel, and that I am not sufficiently qualified regarding modern public policy or economics to speak as directly to these issues. Most nations back then did not restrict entry or control borders to the extent practiced today. It would have violated ancient protocols of hospitality, not only for Israel, but also for most of their “pagan” neighbors. Of course, individuals or families migrating differed from a massive group like Israel passing through someone’s territory. Edom and some other nations perceived them as a threat and turned them away (Num 20:18-21).

So some rightly point out that Abram was not an “illegal” immigrant. (In fact, he was warmly welcomed, albeit partly because Pharaoh took a liking to his wife. A great “me too” passage, but that is for another time.) Neither, however, was Abram a “legal” immigrant in the modern sense. I don’t know how much paperwork he had to fill out, but he certainly didn’t have to wait six months or a number of years to enter the country.

I also recognize that part of the stated reason the U.S. government is separating children from their parents is to prevent detaining them with their parents in unhealthy or penal settings. Part of the stated reason for detaining the parents is that the influx of immigrants is becoming too great for the social systems around the border to handle. (I dislike this reasoning, but while my biblical expertise informs my ethical convictions, nobody consults me on public policy matters.)

It is also true that few nations can think of absorbing all the tens of millions of refugees fleeing violence around the world today, whether from governments or gangs. Happily, some nations, such as Germany, Lebanon, Uganda and Jordan, have been accepting and sometimes absorbing massive numbers of refugees, despite many problems along the way. More prosperous and stable nations naturally do become greater magnets for those in need.

I do not have a solution, but I believe that one ethical component of such a solution that would benefit everyone is to invest heavily in improving the stability of economic development of other nations, not least those at one’s borders. We all know that various factors make this ideal impossible in many places, but a country that could invest in building a massive wall on its southern border (for probably much more than $20 billion) might also be able to make staying at home more attractive for people in some countries.

According to the intergovernmental Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, which supports democracy and market economics, the U.S. ranks a respectable second (at some $31 billion) only to the European Union (at some $92 billion) in development aid to other countries. In terms of its development aid per capita, however, it ranks eighteenth, and in gross national income, it spends closer to 0.17%, ranking twentieth. That is almost $100 for every U.S. resident; many of us as Christians give far more than that through Christian or other NGOs. But Norway, by comparison, invests more than $800 per resident. What we learn from such figures certainly is limited: how money is used often matters more than how much money is used. But my point in citing these figures is to remind us that there remains room for us to do better—at least for those of us with biblical values.

Applying biblical ethics to secular governments?

Again, I have to concede that my above considerations from Scripture do not dictate what the United States must do. Ancient Israel was a theocracy supposed to obey God’s virtues; as an individual Christian I recognize that non-Christian nations will not abide by specifically biblical virtues, such as loving one’s neighbor as oneself (Lev 19:18), loving foreigners as oneself (Lev 19:34; cf. Deut 10:19), or loving or defending the value of all human life. Aside from the issue at hand, I also understand why a nation not exclusively composed of Jesus’s followers might not want to practice Jesus’s even stronger ethic, given to his disciples, of turning the other cheek (Matthew 5:39; Luke 6:29).

Secular nations or businesses or other institutions will not work by Christian ethics. Still, those of us who are Christians had sure better heed these principles ourselves. Moreover, those of us who live in democracies are expected to use our voice and vote to promote values that we hold. Love of neighbor, by the way, also appears as the epitome of biblical ethics later in the chapter that Jeff Sessions cited, in Romans 13:8-10.

Before returning to matters of immigration, one more digression for U.S. readers: what precipitated this post was a Bible quotation used in a political context, not a particular U.S. political party. I believe that, for those of us who do not believe that human life begins only at birth, caring for the vulnerable includes caring for the unborn. Loyalty to Christ must trump any partisan loyalties, whether on the right or the left.

Immigrants in life-threatening situations

Obviously, many people migrate for better economic opportunities rather than life-threatening circumstances; further, some nations might limit others’ immigration for the sake of the economic welfare of current residents (I admit my lack of expertise here).

Nevertheless, sometimes people’s lives are in danger, as is the case for at least some immigrants to the United States from Central America. A law restricting entry in their case would be clearly unjust. I for one would ignore such a law if genuinely necessary to save lives, and would recommend other endangered persons to do so.

Before some readers take me as a political subversive, let’s make that hypothetical situation more concrete. U.S. immigration policies during the Nazi genocide in Europe denied entry to thousands of Jewish refugees, many of whom then died under Hitler. The U.S. did not yet know about the gas chambers or ovens, but by 1938 they knew very well that Germany was persecuting Jews. Congress, apparently in keeping with the general sentiment of the U.S. public, rejected a bipartisan bill to admit 20,000 Jewish refugee children in 1939. You know what came afterward.

What about famine? Abram didn’t face danger from violence, but he did face danger from famine, which can kill people. My wife’s entire neighborhood became refugees during the civil war she was involved in (further details in our book, Impossible Love). They lacked adequate food and clean drinking water. When, after the war, she returned to the ruins of her home, she was overwhelmed by the silence. Most of the neighbor children had died.

Does Romans 13 justify the issue at hand?

Some issues might be debatable, but others are not. The question that started this post is not just immigration. It is the use of the Bible to justify, as ethical, detaining families at the border even to the point of separating children from their parents. The attorney general may have been quoting the verse simply to say that it’s unethical to break a nation’s laws by entering it illegally. In ordinary cases might be true, though again, most Christians would make exceptions for danger to life, smuggling Bibles for persecuted Christians, and so forth.

But Romans 13 hardly resolves the question of whether those laws themselves are ethical. And when given in answer to questions about separating children at the border, an answer implicitly addressed instead to the immigrants is beside the point.

Sometimes the comments people append to articles tell us more about the commenters than about anything else. Trolling betrays the antinomian spirit of the trolls.

Proverbs 18:2, NRSV:

“A fool takes no pleasure in understanding, but only in expressing personal opinion.”

NIV:

“Fools find no pleasure in understanding but delight in airing their own opinions.”

NASB:

“A fool does not delight in understanding, But only in revealing his own mind.”

Comments on Comments

Comments sections are good for free speech and good to invite readers to engage ideas. Unfortunately, sometimes the engagement is at a level of intellectual discourse that requires very little cerebral capacity.

For laughs, on the few occasions when I used to have some spare time, I sometimes would read comments sections. Such sections often reveal more about the commenters than the articles on which they comment, since the articles may be labeled either too conservative or too liberal depending on the commentator.

Some have been surprisingly well-reasoned (including some with whom I disagreed), and in these cases I often learned to consider angles I had not thought about. Those who offer thoughtful comments should by no means be discouraged from doing so. Some comments, however, reflect astonishing immaturity. I would complain how many appear to be written by adolescents, but I don’t want to offend my daughter or other positive representatives of that age group.

On one YouTube video, where a young woman was simply trying to share a song, a comment below said something like, “You’re ugly. You should kill yourself.” If an adolescent mind gets away with such a comment because it is anonymous, one still is left to wonder what kind of person thinks and speaks this way. For those of us with kids in high school, it is scary to think that some such people may lurk their halls.

Civil Discourse

Candy Gunther Brown, a leading expert on prayer studies, wrote a balanced, concise article for a major outlet. Some suggested that she was ignorant because such-and-such a study had demonstrated the opposite of her conclusion. In a book published by Harvard University Press, she had shown the error of the study that this person cited, but apparently it was the only study with which her critic was familiar, so he assumed that he knew more than she did. Meanwhile, she was concisely synthesizing material from hundreds or thousands of sources, as I also often do.

Academic discourse at its best allows a range of interpretations on the table and then uses evidence to seek to find the interpretation(s) that best fit the data. At least in its ideal form (often observed in the breach), academic discourse refuses dismiss others’ positions without consideration; it also refuses to denounce its interlocutors with ad hominem labeling or with guilt by association. It explores evidence, weighs various options, and (again, ideally) respectfully engages those with whom the author disagrees.

Partisan political discourse, however, has seeped into everything else. Even in academia, discourse is often coarsened today, and every discipline has its share of rude and arrogant voices. But the ideal gives us something to strive for, even if some circles (say, British academia, minus, say, Richard Dawkins) tend to do it better than some others.

Free speech provides the right to say (almost) anything (explicit exceptions include yelling, “Fire!” in a crowded theater). But one can exercise rights responsibly and intelligently, or not. Just because one is allowed to say (almost) anything does not mean that it reflects well on one’s intellectual character. (I do not have in mind here comments that are simply playful or humorous, but those that are dismissive.) Just because one can speak anonymously, without fear of personal consequences, does not mean that one is making a helpful contribution. We live in a society, and if we contribute to the coarsening of public discourse, we ultimately share in the larger consequences.

Proverbs 18:2 remains all too relevant today.