I’m going to

talk about two kinds of leaders in Mark 10:42-45, but the discussion will make

fullest sense if I spend some time in the rest of Mark’s Gospel setting the

stage for this.

Jesus

throughout Mark’s Gospel displays one kind of leadership. Some scholars like to

play Jesus’s “Messianic secret” (his invoking silence regarding much of his

ministry) off against his signs or glory. But they are envisioning the wrong

dichotomy. Throughout the Gospel, Jesus is healing and delivering others, even

at risks to himself. (His times with the marginalized would not commend him to

the elite.) He is not seeking his own honor; his acts of healing are part of

his being a servant to others. Jesus spent time with the disabled, and moral

and social outcasts—he’s not looking to get the powerful to back his cause.

There are also

other kinds of leaders in Mark’s Gospel. These include some of the scribes and

Pharisees, whose confrontations with Jesus show them more committed to their

stringent interpretations of Scripture than they are to the desperate human

needs Jesus is meeting. Still more unlike Jesus are the Jerusalem elite, who

flaunt and sometimes abuse their honor and power. Like tenants in the vineyard

in the parable Jesus tells in Mark 12, these leaders forget that God allowed

them to be caretakers. They do not want to relinquish their power over the

vineyard of God’s people.

We should

expect the disciples to be different. Jesus is training these relative nobodies

to be leaders in his kingdom. Most of them are from modest or poor backgrounds;

most of them were also probably not well-educated (although at least the tax

collector should have had basic writing literacy). They were Galileans, whom

Jerusalemites sometimes viewed as country bumpkins. They should understand that

Jesus is about helping those in the greatest need, not about self-exaltation.

But soon the

disciples, expecting places of honor in Jesus’s kingdom, begin looking like the

other kinds of leaders rather than like Jesus. They try to protect Jesus from

being bothered by children (10:15); other followers want to protect him from a

blind beggar (10:48). After the disciples try to keep away the children, Jesus

has to repeat a lesson he had already given his disciples about receiving

children (9:36-37; 10:14-15)!

And before the

lesson of 10:42-45, they become even deafer to Jesus’s message. After a rich

man refuses to surrender his wealth for the kingdom, Jesus again reminds his

disciples that the first will be last (10:31) and that Jerusalem’s elite will precipitate

his death (10:33-34). Instead of contemplating this sobering warning, James and

John immediately ask to be greatest in the kingdom (10:35-40). (After all, they

were just on the Mount of Transfiguration with him and Peter, while the other

disciples were failing in an exorcism below the mountain.) This ploy makes

angry the other ten: James and John are butting ahead of them in line (10:41)!

The disciples had already been debating among themselves who was the greatest,

and Jesus had already responded that the greatest would be like a child

(9:33-35). His message, however, has obviously not yet sunk in.

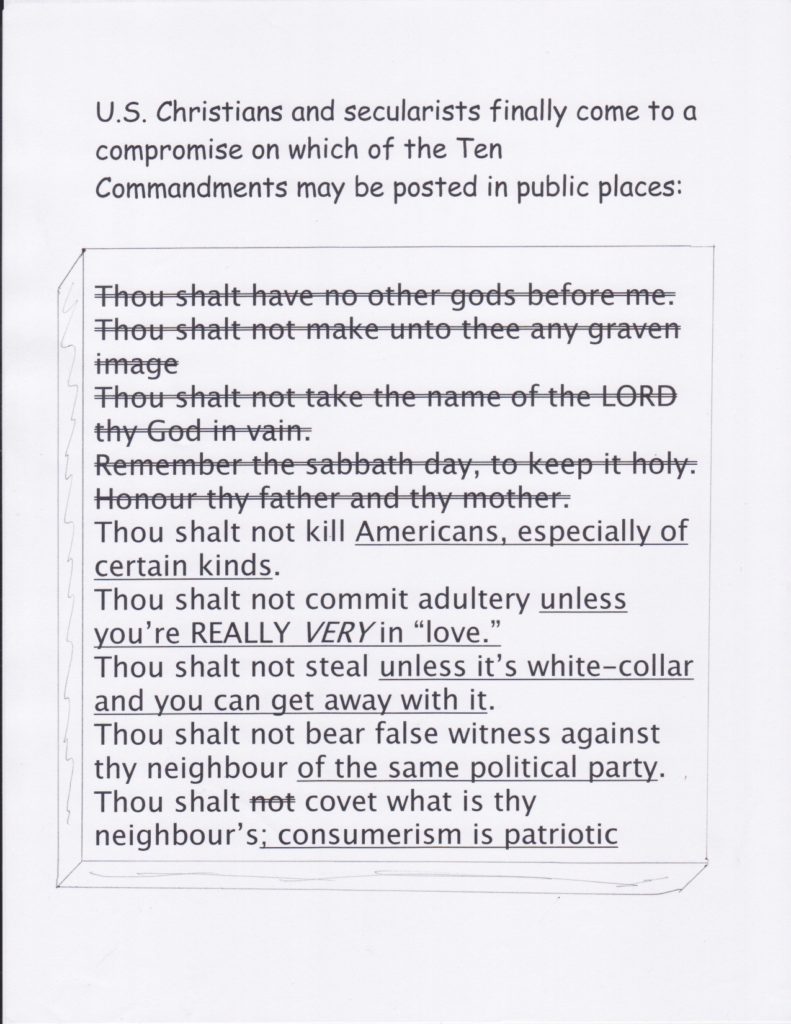

So Jesus gives

the lesson in 10:42-45. Here he contrasts two forms of leadership. For the

first, he speaks about the world’s way of power, exemplified by the “rulers of

the gentiles” (10:42). (Keep in mind that, for Jesus’s Galilean disciples,

gentiles did not exactly epitomize moral ideals.) This was the sort of raw

power that allowed Pilate to hand Jesus over for execution or for the Jewish

tetrarch Herod Antipas to have John beheaded (though both Pilate and Herod

succumbed to others’ demands in these cases). By Galilean standards, Herod even

seemed a “king” (6:14, 22, 25-27).

This differed

from the ideal kind of rulership, the reign of God, his kingdom, proclaimed by

Jesus (1:15). This divine kingship would someday be manifested in the glory

that God’s people were expecting (14:25; 15:43), but it first came in a hidden

way—the humble “secret” or mystery of the kingdom I’ve already mentioned

(4:11-12). It is a kingdom that belongs to children (10:14-15), inimical to

power based on wealth (10:23). And the language of king, besides the

pseudo-king Herod, clusters in Mark 15, when his enemies mock Jesus as king of

the Jews (15:2, 9, 12, 18, 26, 32) and crown him with thorns (15:17).

The rulers of

the gentiles exercise authority in self-seeking, abusive ways (10:42). By

contrast, Jesus exercises authority not like the scribes (1:22), but for

driving out demons (1:27) and forgiving sins (2:10). He delegates this

authority to his disciples—also to drive out demons (3:15; 6:7), waging war

against the enemy kingdom of Satan (3:24-27).

In contrast to

the power of gentile rulers (10:42), Jesus offers a contrasting paradigm

(10:43-44). “This way of the gentiles—that’s not how it must be among you.

Instead, whoever wants to be great among you will be your servant, and whoever

wants to be first among you will be slave [doulos] of all” (10:43-44).Jesus uses power to heal the sick (5:30), not to help himself (15:30, 32;

cf. Matt 4:2-4).

Unfortunately,

this is not the first time Jesus had had to offer this lesson: he has to keep

reminding them! In 9:33-34, the disciples had been discussing who was the

greatest among them. Jesus then warned them in 9:35 that whoever wants to be

first will be last and servant of all. Now again James and John had sought to

be highest in the kingdom, and Jesus has had to repeat the lesson. Our habit of

competing for honor or attention dies hard.

Yet Jesus is

not offering mere abstract instruction. He is offering himself. And insofar as

he is our hero, our model of greatness, humbling ourselves must become our

ambition! Our Lord is greatest of all, having humbled himself most of all:

though being divine, he humbled himself, taking on him the form of a servant,

and became obedient to death, even the particularly shameful death on a

cross—the ultimate humiliation. Yet God has exalted Jesus Christ as Lord of the

universe! (Phil 2:5-11).

And so Jesus

gets specific, in 10:45 essentially adding another passion prediction that

brings them back to the subject that preceded the quest for greatness

(10:33-34): Jesus, the Lord himself, must die. “For even the Son of Man did not

come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life as a ransom for many.”

Mark’s entire

Gospel shows Jesus serving, a servanthood that climaxes in Mark’s lengthy

passion narrative. “Ransom” (10:45) often meant the price used to buy someone

from slavery. Jesus by his own life offers himself as a slave (10:44) to free

us from slavery. We could not have saved our own lives for eternity, but Jesus

does. In 8:37, Jesus asks what a person can give in exchange for their soul (antallagma

psuchê). Here Jesus says that he gives his own life (psuchê) in the

place of (anti) many. He gives his life in exchange for ours.

We whom God

had graciously appointed as leaders—some of us from lowly backgrounds like the

disciples—have a special privilege and opportunity to serve all the more. May

we always remember our Lord’s model: for how can we ever serve as humbly as he

has served us?